The decision to expel the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (Numsa) may be described as the end of an era, but what the numbers show is that trade unionism in South Africa has been experiencing fundamental shifts and a downward trend for years.

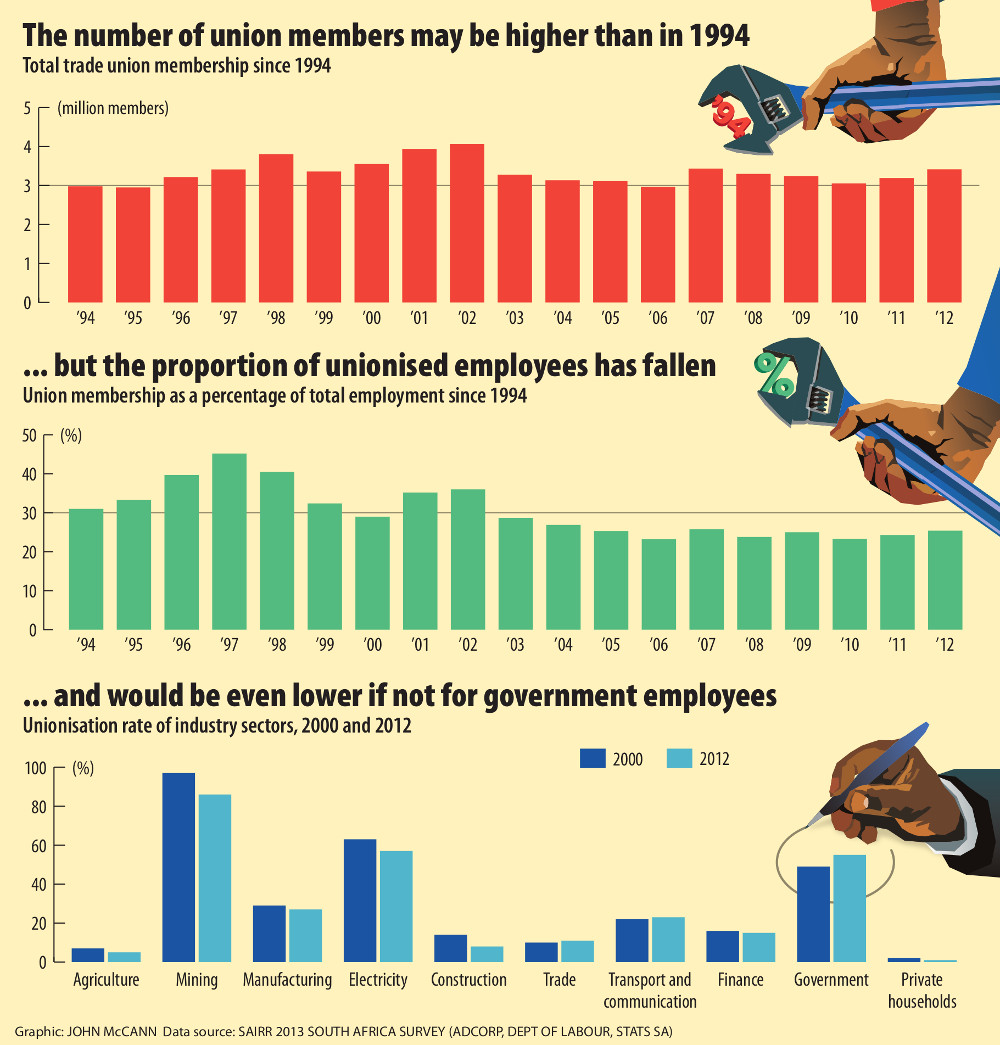

Trade union membership grew from 2.9-million in 1994 to 3.4-million in 2012, according to the latest South Africa Survey published by the Institute of Race Relations, which cites a wide range of sources in its data on industrial relations.

The unionisation of the workforce was at its peak in 1997 at 45.2% of total employment and has since dropped to 25.4% in 2012, the survey said. There are 3.2-million unionised workers, but 13-million employees in South Africa at last count. (Statistics South Africa counts temporarily employed workers as employed.)

Although unionised employees typically realise high wage increases, the growing distrust of unions – as reported in some surveys – and more job creation in sectors outside of mining and manufacturing have seen workers steadily losing interest in organising themselves.

Although numbers are dwindling, South Africa is on a par with developed economies such as Canada and the United Kingdom. It is lower than Sweden, which has a unionised rate of over 65%, but higher than an aggregate 16.7% for Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, which are, mostly, developed.

Still, Cosatu has aimed for a membership of more than four million by 2015. It is way off target – especially if other affiliates leave in protest against Numsa’s expulsion.

Devan Pillay, professor of sociology at the University of the Witwatersrand, said: “[One] obstacle is – we have to face the fact – the increasing oligopoly in the unions.”

Cosatu and some of its affiliates have come under criticism in recent years for complacency – stemming largely from its representation of 65% of the unionised workforce and having enjoyed majority union status in many sectors for an extended period of time. A resultant growing distance between shop stewards and members has left many workers feeling unions are not servicing them as well as they might expect.

“Numsa has revitalised itself on that score – because it has done that. Workers are flocking to them – that has caused part of the difficulties they are facing,” said Pillay, referring to disputes between Numsa and other affiliates that blamed the union for organising on their turf.

Public sector boom

“Over a period since 1994 – there has been either declining or no growth in private sector trade union figures – most growth has come from the public sector,” said Haroon Bhorat, director at the development policy research unit in the school of economics at the University of Cape Town.

South Africa’s trade union figures have been buoyed largely by the growth in the public sector and unionisation in the civil service. The Institute of Race Relations’ survey shows that 55% of government was unionised in 2012. A third of this category, however, included other community and social services.

An economist at the Free Market Foundation, Loane Sharp, said a more accurate picture would be to strip this third out – in which case the public sector would be 81% unionised.

Private sector unionisation is buoyed by mining. At 86% of employees, the mining sector has the most unionised workforce. This high rate is for historical reasons: dismal work and pay conditions, as well as the centralised nature of a mine, provided optimal settings for organising labour and entrenching trade unionism. Closed shop agreements, by which jobs are contingent on union membership, have been common in this sector.

Sharp said that if mining, along with the civil service, is excluded, just one in eight workers would belong to a union. Bhorat said public versus private sector unionism was an important distinction because “public sector unions are a different animal” and represent a different share of the workforce.

The agreements made there can have a serious impact on the rest of the economy because the public wage bill is a big factor for the fiscus.

“The public sector have become wage setters in their economy and have a crucial role to play in thinking through wage formation in the economy as whole,” Bhorat said.

Sharp said public sector workers were paid out of tax money, whereas private sector jobs were “self-funding”.

Pillay said: “The rapid rise of the public sector has displaced the focus of Cosatu. The public sector is typically better educated and has middle-class aspirations.”

But organisation in this sector was still necessary.

“The state can be as brutal at suppressing the rights of workers if they are allowed to and in many cases they have been allowed to.”

Higher wages

Being unionised will probably mean a high wage increase for a worker.

The Institute of Race Relations survey shows 52% of Cosatu members earn more than R5 000 a month, as opposed to just 22% of other workers. The bulk (38%) of Cosatu members are low-skilled workers and labourers; and 28% are skilled production workers.

The highest average monthly wage is in the electricity, gas and water industry at R28 500 – a sector hotly contested by the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) and Numsa.

Union to employer negotiations tend to yield better results for the workers. These accounted for 21.4% of wage negotiations in 2013. Negotiations between an individual and their employer accounted for 10.3% in that year. Bargaining councils comprised 8.9% of negotiations.

Of the higher wage increases realised by union and employer negotiations, Sharp said: “I wouldn’t say they achieved it. I would say, rather, unions represent generally better paid, better skilled and more experienced workers.”

Cosatu’s own 2012 Workers Survey found that “union members are typically older, better paid, and better educated than other formal sector employees”.

Still, higher wages don’t appear to be incentive enough to entice workers in the private sector to unionise more than before and changes in the structure of the economy could be to blame.

As Bhorat noted, the most job creation is happening in financial services where skilled, professional employees are less likely to want to join a union. This sector is also one of the few contributing to economic growth at the moment, but does, however, offer logistical challenges for organising labour.

“If there is one mine with 60 000 people, it’s very easy to just send two union officials in and organise that mine,” said Sharp. “If you move to a services-based economy and you consider a bank has 750 branches around the country, it becomes a lot more difficult. There is no way unions can afford to canvass a small to medium enterprise employing less than 50 people.”

Bhorat said unions were either organisationally weak and unable to recruit, or they lacked resources to do so. He noted this was aggravated by the fact that many leaders had left the unions to move into government post-1994, leaving a “skills deficit in the trade union movement”.

Pillay cited “informalisation” of the private sector as another major obstacle. “Higher levels of informalisation in the private sector is a global phenomenon,” he said, noting capitalism sought to bring down labour costs and was doing so through informalisation, such as using labour brokers.

“Unions see it as a technique to bypass labour laws,” Pillay said.

Losing touch

The Institute of Race Relations survey showed Numsa had increased its members by 34% between 2006 and 2012. The NUM, however, formerly the largest Cosatu affiliate, dropped to fourth place last year after losing 40?000 members between 2012 and 2013.

Research from the Human Sciences Research Council, quoted in the Institute of Race Relations survey, found that, between 2011 and 2012, public distrust of trade unions grew particularly among black Africans – growing from 21% to 35%. It also increased most in the lower and working classes.

In Cosatu’s 2012 Worker’s Survey, around a third of union members said there was corruption in their unions, although fewer than one in seven said they had personally experienced it.

Given the underlying downward trend, and now the expulsion of Numsa from Cosatu, Sharp said: “I think what we are seeing here is the permanent demise of the union movement. It’s like a bubble in the stock market. You know it is there but you don’t know when it is going to burst.”