Wangechi Mutu’s depiction of the black female form explores current experiences and the way history and politics frame and shape that experience.

The University of Cape Town’s Hiddingh campus hall is buzzing with noise. Already a few empty wine glasses lie discarded in corners, drained in excited anticipation. We are waiting the arrival of the celebrated collage artist, Wangechi Mutu.

Between the shrieking mic and the sonorous whispers of the fidgety crowd, a voice approaches the stage announcing that the guest speaker is running late, delayed by the Robben Island ferries that transport visitors to and from the heritage site. But in no time in glides the tallish, statuesque figure that is Mutu.

Beginning her lecture, the artist reads a short meditation jotted down while in transit. As she begins to recite, I remember the words of the late jazz saxophonist Zim Ngqawana who once said he would only visit “the island” as a prisoner. I have also refrained from visiting Robben Island, a decision inspired by a fear of the sea rather than something grand like taking a political position.

Mutu takes us through the painful encounters of the island’s cold seaboard to a different time and place as a way to locate her work’s premise. Born to a middle-class Kikuyu family in Nairobi, Kenya, in 1972, she spent her formative years there until she moved to Wales and then the United States to study fine arts. Despite her move abroad, and more specifically to Brooklyn, New York, where she lives, Mutu has kept a close relationship with Africa, its history and people. This is something one picks up in the powerful collages she creates.

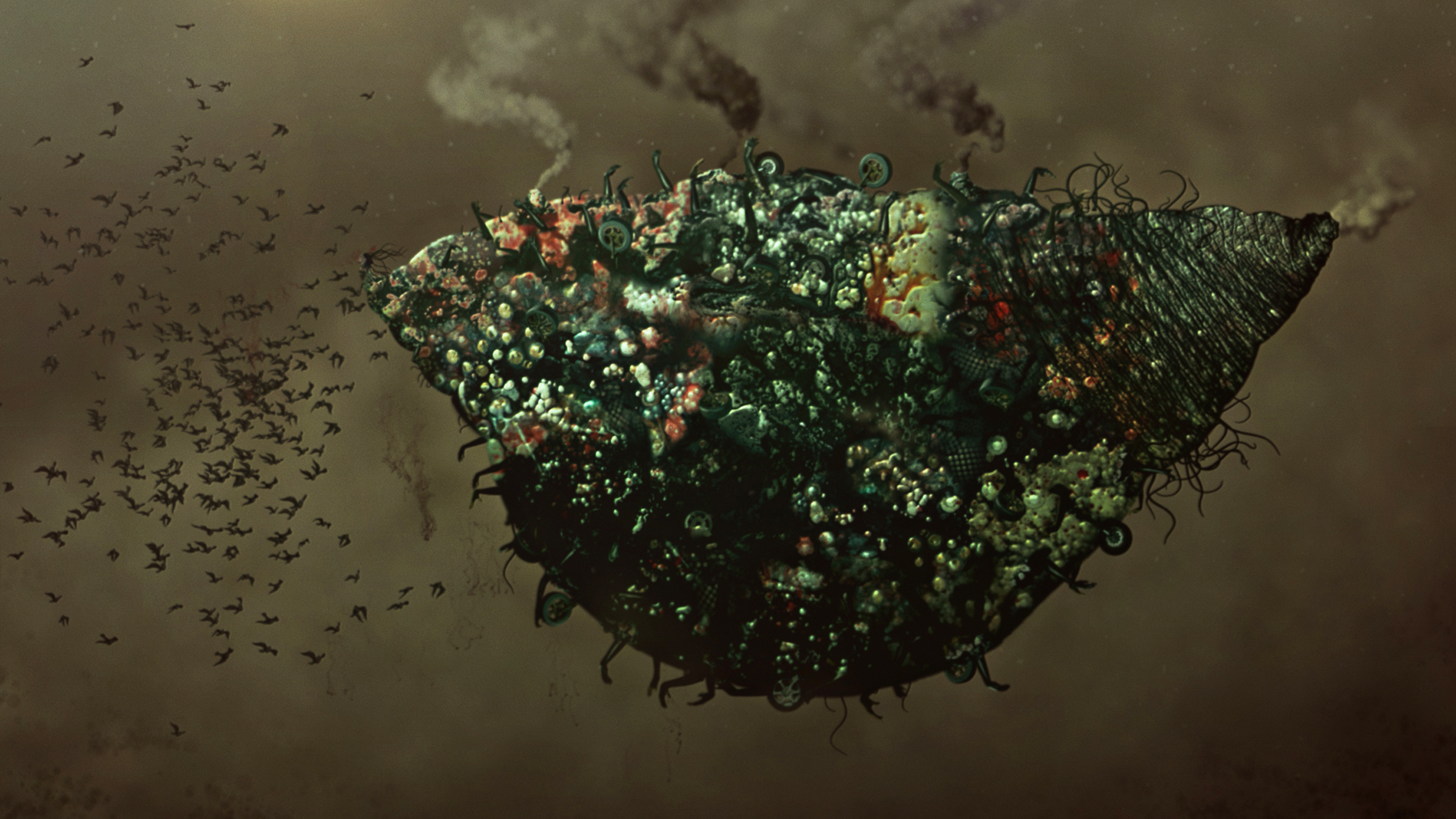

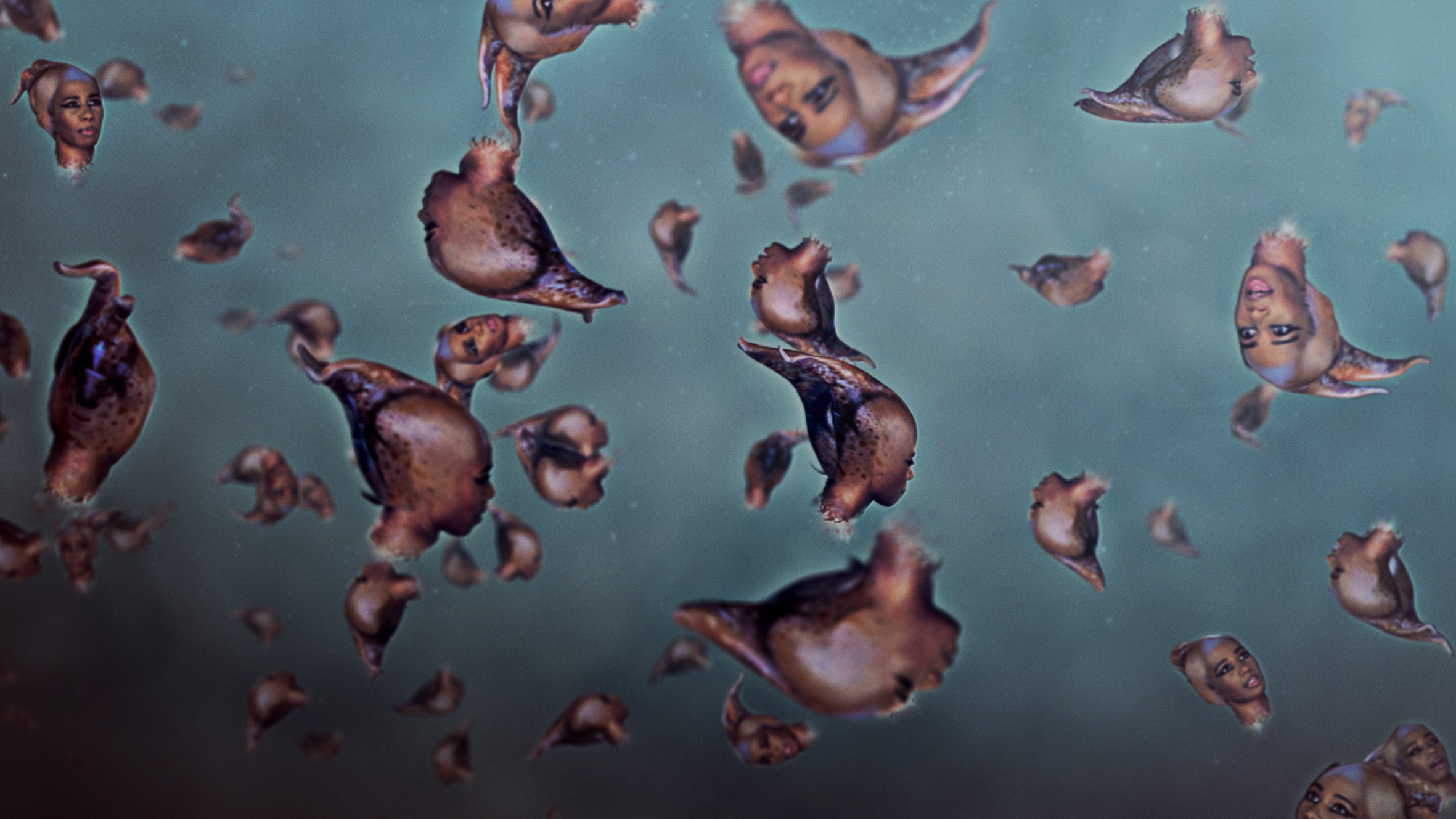

Though this was the artist’s first trip to South Africa, her work is no stranger to these shores. This time around Mutu’s work is part of the group exhibition titled Kings County, on show at Stevenson Gallery in Cape Town. It features her video, The End of Eating Everything. Alongside Takashi Murakami, Chris Ofili, Howard Hodgkins, Harry Corry Wright and Donald Robertson, Mutu is one of six artists chosen to create two of the six unique covers of the Bazaar Art supplement in Harper’s Bazaar art edition. But this is not where she begins.

‘A body marked by a terrifying absence’

“The reason I start with the continent, for me, it is because it is the end of something,” she says. “That moment in 1884, during the Berlin Conference when those 15 European men sit there and divide a continent they know little about, into sections that they own. This is the end of a moment.” Despite Mutu’s insistent reference to colonisation as a significant moment in her work, this is her least explored side. Often, it seems, writers are content with just darting past it. “There is a lot of nonsense too,” she says, referring to some interviews online.

During the talk she would not answer a question about her personal life. “People want to know all sorts of shit,” she told me privately. Bathing in the yolkish yellow of the light, Mutu took us through screened images of a beginning not as gratifying as is usually the case. This is a beginning marked by end – death. “I don’t know much about my great-grandmother’s life; how she walked around her farm and raised her kids and stuff. There is such a massive cleave – a cut – in history that is so severe in every direction. It is severe spiritually, historically and on peoples’ bodies.”

And since the creation of the modern world the black body has had a paradoxical meaning as the bogeyman in European consciousness. It has variously appeared in the neat racial categories as uncivilised, lacking, ugly and “thingliness”. Whether represented in visual or textual contexts, it was a body of inhumanity and disgrace – predisposed to torture, derision and abjection. It was a body marked by a terrifying absence – the human face. And, ironically, as the world “changes”, these views have shown durability, elasticity and have consequently been heightened in everyday lived experiences of black people around the world.

“We are a self-flattering human race. We sitting here sort of evolved – oh, we’ve got democracy, human rights and we’ve got this and that. It is not true. We have been really brutal to each other. Also, we work really hard to act like it didn’t happen,” she says. There is a curious collectivisation in Mutu’s words, the “we” and “each other”, that sometimes suggests black people’s culpability in the historical instance. In light of the varied post-colonial, postmodernist and feminist critiques, the body has returned, most specifically in visual arts, as a site of questioning these political and social histories.

‘A reaction to history’

Influenced by artists such as Ana Mandieta, Kerry James Marshall and Richard Onyango, whose work focuses on the body, Mutu’s work recovers the black body as a “reaction to history”. History and body weigh heavily on Mutu’s general conceptual itinerary and creative work. Her work focuses not simply on current experiences of black female bodies and their uses and abuses in society generally, but on how history, more politically, continues to frame and shape the black experience.

On the one side, she appropriates the negative meaning attached to the black female body and transforms it into a site where multiple layers of meaning, histories and forms can be read. From her earlier work to her more recent work, the body is dissected and fragmented. It appears as something incomplete, held up in scaffolds and patches. In the first encounter we’re repelled by its overt uninviting appearance; macabre and pornographic displays. For Mutu this obsession with the negative point and the traumatic is the truest way to reflect society.

“People don’t stop when they see something normal on the street. They stop when something awful has happened,” she says. “It symbolises something transitional from life to death, from safety to danger and from normality to absolute.” This uncertainty is another element and feature that reigns in Mutu’s work. Though we can deduce certain features that bring her figures back to life, or identify with those less disheartening moments, death never fully disappears. The binary between ugly and beautiful and life and death is never fully overcome, but negotiated.

“Many people ask me, ‘how do you do these pretty things and mix them with the violence?’. Because it is how they are. And for many people it just perhaps costs too much to look at reality.” This persistence on depicting, back to back, the monstrous and pleasant – occupying a place of indecision – is the most interesting way to read Mutu. That is, to think constantly of the insanity of black existence as a struggle to negotiate ways of reconciling incommunicable instances.

It is an intersectional space that seems to render time as continually in suspension and unchanging when it comes to black people and, more specifically, black women, according to Mutu. For her there is no significant and intelligible break between early sacrificial experiments of abortion on enslaved women and today’s nonchalant use and rendition of black female bodies as phobogenic things.

Similarly, in her work, time, a feature as implicit as death, collides within a single frame in various ways, especially how figures seem always suspended in contexts that can’t be represented through the white background. Growing up in a country of settler colonialism, another important issue for Mutu is the relationship between black women and the land and nature. “Land is life in Kikuyu culture,” she says. “That meeting of those 15 European countries was the beginning of the death of our people. So we had to get our land back.”

Myths, nature and ecology

Unlike in her earlier pieces, her recent work is infused with the body, myths, nature and ecology. At first glance this correlation between the black female body and nature seems to reinforce the stereotypical pairing of woman as part of the ecosystem in more derived ways. “I don’t think my obsession with ecology is separate from my obsession with the body. I correlate them because this is how I see them.”

But for Mutu this is not a question of whether the woman is, in the larger scheme of things, an extension of nature. As much as she cannot ignore these easily reproduced clichés of “putting women close to the earth”, she claims she cannot ignore how “women engage with nature in order to supply life to their families”. This fact, she reckons, must not be dismissed. From talking about the Berlin Conference, the Mau Mau, Frantz Fanon and ecology, Mutu always goes back to the woman question, the body. But, most importantly, she states that her work reflects her own experiences as a black woman and of those she relates to.

“Making this work, I guess I am trying to unearth myself. I am trying to dig myself out of the possible grave we were put in and every single thing we were told needs to be put into question.” This emerging from the grave – from death rather than grotesque – is the struggle that resides in the deepest of places in Mutu’s work. Unlike birth, emerging from civil death or speaking from the position that is always muted, provides an alternative way of thinking of Mutu’s oeuvre. And I suppose to work from, confront and stand against one’s own death, as Fanon would say, makes one a revolutionary and it certainly challenges our own illusions about ourselves.

Perhaps from this perspective, we might argue that Mutu’s work looks beyond the issues of representation and identity important to post-colonial thinking towards a more resolute critique of how colonisation, systemically and systematically, reproduces itself in daily lives of black female bodies.