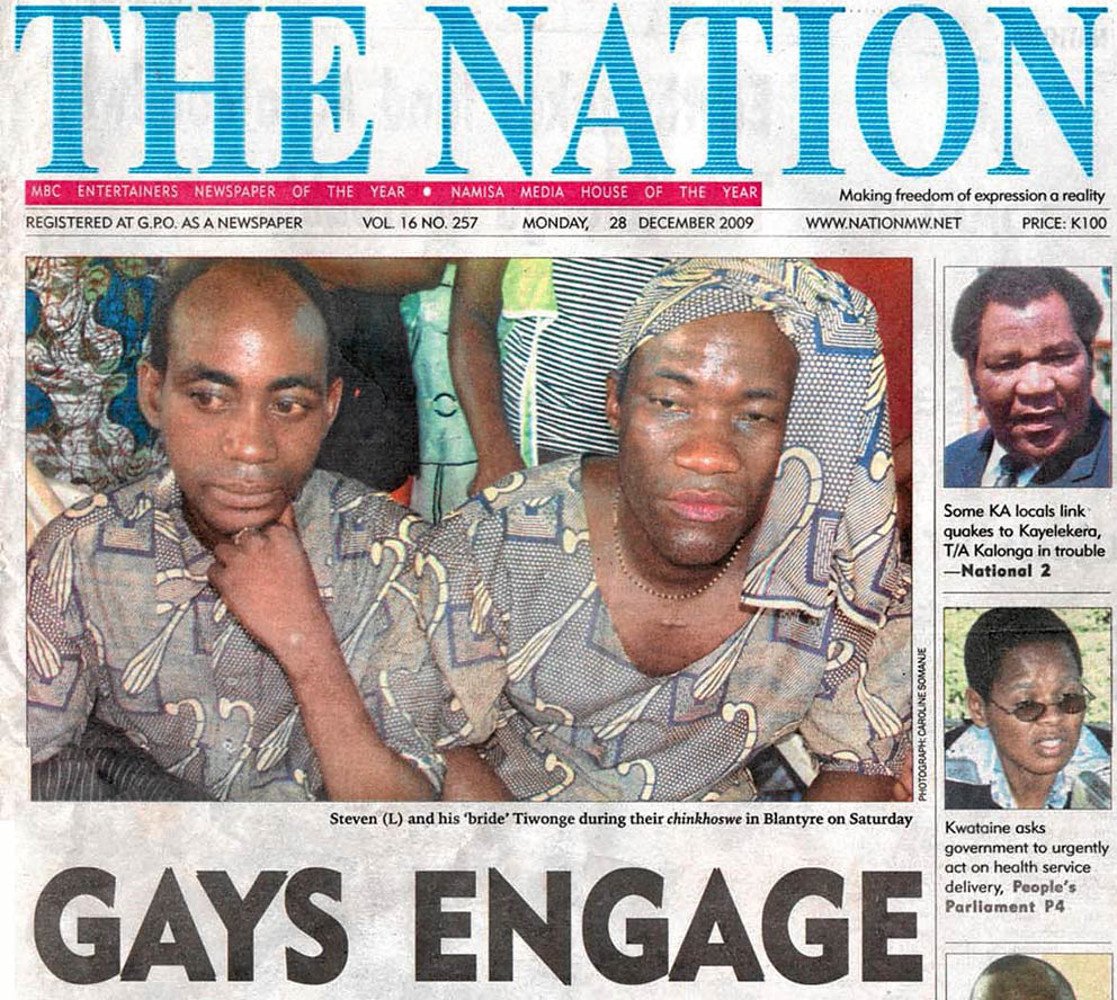

“GAYS ENGAGE” – this was the headline on the front page of Malawi’s daily Nation newspaper on December 26 2009, beneath a photograph of Tiwonge Chimbalanga and Steven Monjeza, bleary-eyed and uncomfortable in matching his-and-hers outfits cut from the same wax print.

The story’s first paragraph reads: “Gay lovebirds Tiwonge Chimbalanga and Steven Monjeza on Saturday made history when they spiced their festive season with an engagement ceremony ( chinkhoswe), the first recorded public activity for homosexuals in the country.”

Front page. (AFP)

Two days later, the couple was arrested and charged with “carnal knowledge against the order of nature” – a hangover from the British colonial penal code – which had never been used against two consenting adults in Malawi. They were given 14 years’ hard labour. It was, the judge said, “a scaring sentence”: there was to be no more of such nonsense.

During the trial, several people would testify that Chimbalanga had deceived them into believing she was a woman: she had explained away her male features by saying she had been born a girl but was bewitched as a child. Expedient though this explanation might have been, it is probably close to how she actually felt, given that she has always understood herself to be female.

“I am a woman,” she told me firmly five years later, as we sat in her two-roomed shack in Tambo Village in Gugulethu on the Cape Flats. She has been in exile in South Africa since 2010. Amnesty International declared her and Monjeza “prisoners of conscience”, and brought Chimbalanga to South Africa after they were eventually pardoned by Bingu wa Mutharika, who was then Malawi’s president, after five months in jail.

By township standards, Chimbalanga has been receiving a generous amount from Amnesty: R4 000 a month. She has a television and a sound system – and a coterie, including her partner of about a year, Benson, a Malawian man who lives with her. Neighbours are constantly popping in to borrow some mobile airtime, to cadge a tomato or to settle in for some beer with “Aunty”, as she is universally known.

“Aunty!” they exclaim, somewhere between affection and mockery, as they pass her security gate. She says she is 28, but she is probably about a decade older. Tall and ungainly, she would stand out anyway, even if she did not wear the elaborate Malawian costumes that put her at odds with the lycra-leggings female style of the township.

On the street, she walks in the determined manner of someone who seems like she will collapse if she does not keep her chin forward. She accompanies Benson to the shops to protect him from the insults: she has clearly learned to use her fists. But when she curtsies in greeting and fails to meet your eye, you remember that she is just a rural girl from a small village in a tiny, underdeveloped country in central Africa.

International campaign

The international campaign to secure her pardon and resettlement in South Africa represented a triumph for the global cause of LGBTI (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex) rights. But for Chimbalanga, who unexpectedly found herself on the front lines of an intensifying battle over these rights in Africa, there is little sense of victory. The Amnesty grant will run out in a few months’ time and she has few other sources of income. Despite intensive English lessons, she can still not speak the language well enough to enter the job market. And her body is covered in scars: she has been attacked at least five times since moving to Cape Town. She is now applying to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees for resettlement in a third country, a tortuous process that can take several years.

Chimbalanga was raised in a village on the edge of the tea plantations of Thyolo where, she says, she was accepted as female. “When people insulted me, my family made a complaint, and the culprits were taken to traditional court and fined some chickens.” Orphaned, she lived with her uncle, the village chief; he was divorced and she performed all the female household tasks until he remarried.

Her family told me that as a child Chimbalanga dressed as a boy but that everything else about her was feminine – so much so that she was frequently the object of derision.

After eight years of schooling, she left the village because, she says, she had been bewitched and needed to seek help from a traditional healer in the north. When she returned two years later, she was dramatically different, living entirely as a woman and with a new name.

She believes that the healer did release her from the curse – and perhaps it was a release from the constraints of gender that society had imposed on her: away from home, she found the courage to reinvent herself so that her exterior could begin matching how she felt inside. At home, some people accepted her but others still will not, including her sister. In Blantyre, where she lived, she often defended her dignity with her fists.

She has never thought of herself as “gay”, she told me. Indeed, the first time she heard the word was when she saw it written under her photograph on the cover of the Nation. And the first gay people she met were the activists who came to see her in prison once she was arrested.

Mobilising support

One of these was Gift Trapence, who runs the Centre for the Development of People (Cedep), an LGBTI rights advocacy organisation. Just weeks before Chimbalanga’s chinkhoswe, Cedep’s offices had been raided and its safer-sex materials confiscated as “pornography”. Now the authorities suspected Cedep of having deliberately staged the chinkhoswe with foreign backing, to test the waters.

In truth, Trapence had never before encountered Chimbalanga or Monjeza, and had first heard about the chinkhoswe when he read about it in the Nation. He immediately set about organising legal defence for the accused and mobilising international support. The arrest “was on the radio shows, in the taxis, on the pulpits; it was as if Malawi itself was coming to an end”, he told me. “We had to go underground and so did the gay community. It was very traumatic.”

Blantyre came to a standstill every time the two appeared in court, the streets clogged with onlookers. The accused were subjected to humiliating physical examinations and sent for mental observation; the media coverage was both salacious and contemptuous. Chimbalanga, usually wearing a traditional chi-tenje wrap and a feminine blouse, stood her ground: television footage shows her slapping away hands trying to touch her as she is transported to court in an open truck. At one point, she collapsed from malaria and vomited in the courtroom, and was left to lie in her own mess.

Malawi briefly became international headline news. Western aid agencies began threatening to cut programmes. Eventually, UN secretary general Ban Ki-moon came to Malawi. He addressed the Malawian Parliament, called for the repeal of anti-sodomy laws worldwide and met Mutharika. Afterwards, the president said he had decided to forgive the two, although he found their actions to be “disgusting, demeaning and a disregard of our culture, religion and laws”.

After their release, they fought and two weeks later Monjeza left Chimbalanga for a sex worker, whom he introduced to the media as his new wife. As for Chimbalanga, “she couldn’t walk in public without being mobbed”, Amnesty’s Simeon Mawanza said. Without sustained psychological counselling, she seems to have found ballast both in heavy drinking – “It helped me to forget all my problems,” she told me – and in an embrace of her notoriety. As Dunker Kamba of Cedep put it: “She became a queen.”

Asylum in South Africa

She needed to get out of Malawi, and Amnesty arranged for this to happen. Because of her celebrity, she sailed through the asylum application process in South Africa in record time when she arrived here in October 2011. She became one of the first refugees to be granted asylum in South Africa on the basis of discrimination because of sexuality or gender identity.

She was settled in Cape Town, largely because a local transgender advocacy organisation, Gender DynamiX, had offered to host her and administer the Amnesty grant. GDX, as it is known, arranged accommodation in a self-contained flat at a shelter for abused women and enrolled her at a school for refugees to learn English.

But life became “very lonely for Aunty”, her asylum lawyer, Lusungu Kanyama-Phiri, told me. “Here she was, trying to start a new life, being who she wants to be, but she’s confined to a rehabilitation centre with no men allowed and a curfew. When she does sneak out to get herself something to drink and have some company, she finds herself recognised by Malawians who abuse her.”

Within four months she was violently assaulted twice, left unconscious and admitted to hospital. The shelter was struggling with her nonadherence to its rules. She was moved by GDX to a flat in Tambo Village near GDX’s offices in Manenberg and when that didn’t work out, it was decided to purchase the shack for her with some of the Amnesty funds. At around the same time, in mid-2013, she dropped out of school. Her teachers, whom I met, are convinced that this was at least in part because of untreated post-traumatic stress disorder.

Her relationship with GDX soon broke down. Liesl Theron, then the centre’s executive director, thinks that the problem had its roots in the way she was “coddled” at first. “At one point we had six staff members running after her. We realised that Tiwonge couldn’t be our only project and so we started withdrawing some of that very visible support, not least because we felt she needed to start looking after herself while there was a little bit of money left in the Amnesty grant, as a safety net. But I think she must have experienced this as abandonment.”

Her day-in-day-out minder was a GDX employee named Charlie, who also lives in Tambo Village. They are estranged now, although he said he still feels great affection for her.

He tallies the damage that celebrity has done: not only that it gives her airs and graces – she would not, for example, countenance hawking vegetables on the street, as many other immigrants do – but also that “people recognise her: ‘Oh, wesaw you on TV, Aunty! Let’s meet! Let’s drink!’ Then the money’s finished.”

Chimbalanga never has enough, and the people at GDX believe – as the current director, Sibusiso Kheswa, puts it – that this is because “she uses much of it to buy protection, to build a community around her, including securing lovers who don’t have incomes for themselves”. This is a common situation for transgender women, and not just in Africa. But such relationships can be abusive and turn – literally on a penny – from protection to threat, and Chimbalanga lives in fear of that.

Attacks

Several of the attacks on Chimbalanga have taken place in or around shebeens, and she tells me that she has stopped frequenting them for this reason. Still, she believes Tambo Village has become too dangerous for her and she and Benson want to leave.

Benson, aged 40, is mild, ineffectual and inebriated. A few weeks ago his kinsfolk arrived, hauled him into the street and demanded he leave “the moffie”. When he refused, they beat him until Chimbalanga’s landlord called the police, who came and broke it up. Benson’s relatives spat at Chimbalanga: “You take care of him now. We want nothing more to do with him.”

Chimbalanga understands, she says, that her Amnesty funding will soon run out and she is trying to find other ways of living. She has started selling vegetables from behind her home, and she volunteers twice a week at People Against Suffering, Oppression and Poverty, a refugee rights organisation, for which she receives R150 a day. Here she helps asylum applicants to fill out forms, and she is much liked by staff and clients alike.

She say she wants to stop drinking and to begin taking oestrogen. But she has twice missed her introductory appointments at the Triangle Project, the LGBTI health service that refers transgender people to a free hormone therapy programme at Groote Schuur Hospital. “There was no one to take me,” she told me. “I don’t know my way around.”

Language, of course, must be a barrier, particularly when it comes to intimate consultations with a doctor or therapist. But the issue might lie elsewhere too: she does not think of herself as “transgender”, a term she heard for the first time when she was introduced to GDX. As Cedep’s Dunker Kamba puts it: “Because she feels herself so strongly to be a woman inside, she does not understand that she does not look like one.”

Ronald Addinall, the gender specialist who runs the programme at the Triangle Project, told me this was a common phenomenon among his clients. “Sometimes you want to say to a person: ‘Let’s get real here. This is what you need to do to survive.’ But when you’re talking about someone who has fought so hard to have their own identity, constantly having to fight people telling them that they are not what they know themselves to be, that sense of self needs to be respected.”

All those who have tried to help her – and there are very many indeed – feel some exasperation at Chimbalanga’s lack of progress, but also deep remorse for not having been able to do more. It seems wrong to blame her for her difficulties; it’s wrong, too, to blame her benefactors for creating a dependency trap.

If she is a victim of anything, it is of an Africa trying to square modernity with tradition, of a time and a place where the old ways of doing things are falling away and the new ways have not yet established themselves. She is a victim of an incomprehensible world where you can still be awarded a chicken by a village court as reparation when insulted for living as a woman and yet be sentenced to 14 years’ hard labour in the city for the very same thing.

The global LGBTI rights movement, which came to Chimbalanga’s defence when she was arrested, rescued her from years in a brutal jail and probable death while captive. But having evacuated her out of necessity from all that was familiar to her, it cannot provide her with the sanctuary she needs. Perhaps this is because “LGBTI” is an ill-fitting vestment itself – one that cannot, with its current global cut, clothe an uneducated female, born in a male body, from a remote village in central Africa, transplanted into a foreign metropolis.

This is an abridged version of an article originally published in the Guardian. Read the full version at theguardian.com