Photographer Zanele Muholi’s new book of portraits gives visual voice to the plight of ‘queer’ black women.

It is no coincidence that the publication of South African photographer Zanele Muholi’s latest book coincides with the campaign for 16 days of activism for no violence against women and children. Each year the campaign is a chilling reminder that violence against those who are deemed vulnerable has become a disturbingly intrinsic part of the South African psyche.

It is one of those campaigns that should not require special days set aside to highlight its severity, but perhaps this is where the nexus between Muholi’s work and the mainstream media lies – where this relationship starts to transcend the medium of photography.

Following her debut in the contemporary art realm, Muholi’s work has been guided by an iconography rooted in the tradition of black-and-white photography as well as that of portraiture. Faces and Phases 2006-2014 (Steidl) is thus as much of a curatorial project as the exhibitions of Muholi’s award-winning work have been. In this publication, however, there is a peculiar emphasis on allegories relating to religion, history and aesthetics.

Its size and shape, for example, resembles a Bible and the 365 pages can in some ways be read as daily scriptures, all of which encompass a reality of violation and discrimination cloaked, paradoxically, in a message of self-love, triumph and acceptance.

Constructing a narrative

As a publication framed by contemporary art practice, it employs a range of strategies for the viewer to interact with its content. These highlight the publication as part of a selection process, one that begins to construct a particular narrative. It’s a narrative that, unlike the often confrontational nature of Muholi’s exhibitions, creates a sense of intimacy and personal space, both in its format and in the inclusion of testimonies, memoirs and poetry by her subjects.

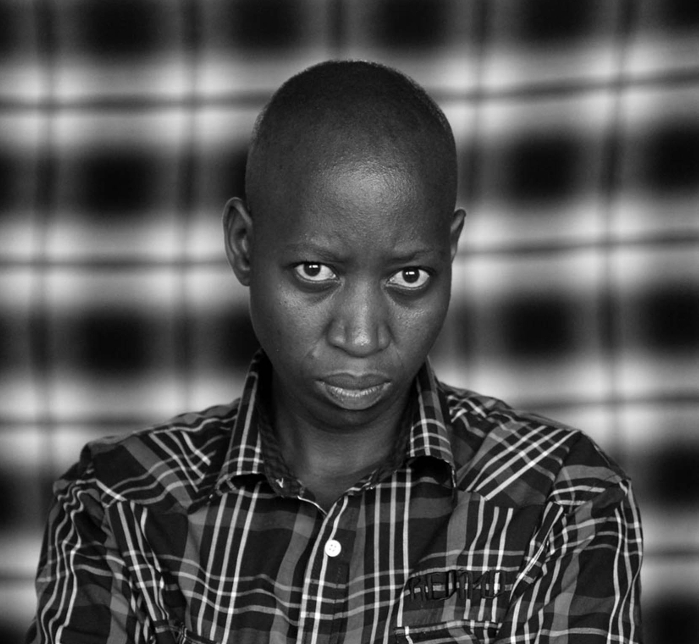

The first image in the book is a posed portrait of a young woman standing against a dark, blurry background. Her lips are shut as if in protest, yet her eyes stare empathetically out of the page. She is wearing a floral shirt and her shoulders are slightly slouched, seemingly unencumbered by the intrusive gaze of the viewer. Her photograph is followed by almost 250 more portraits of black women who identify themselves as either lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or intersex (LGBTI).

There is a uniformity shaped by the format and size of each image but also by the naming of each person, place and year in which a photograph was taken. Despite this, the accounts given by the participants are not only a large and heterogeneous collection of stories challenging what is perceived as “normal” in terms of sexual orientation, but also about accentuating a sense of sameness.

A representation of history

There is also something revealing about the notion of demystifying normality and its taboos that tends to create a sense of exceptionalism. This ultimately emphasises the very attitudes that one is trying to discourage. One way in which the book does this is with a timeline covering extensive research about hate crimes against LGBTI people in South Africa.

As an attempt to “rewrite” history and by inserting itself into a particular historical discourse, the timeline forms part of the contested terrain of portraying a history as opposed to advocating for a representation of histories.

Although it is informative and necessary as a resource that maps a chronology of significant events, it places itself and the book within a particular ideological framework. Like Muholi’s subjects, it falls victim to omissions that are critical fragments of the larger picture of queer studies, social justice and ethical practices within contemporary society.

It is also oddly placed at the end of the book, prefixed by an essay that starts to complicate the established narrative of the book itself. Faces and Phases 2006-2014 thus represents Muholi’s own practice in the mainstream – which, although largely defined by her prominence and influential role as a visual activist, invokes an ambiguous space between the personal and the public, convoluted by how her work operates between activism and commercial spaces such as galleries and art fairs.

An authoritative voice

It is not surprising that the publication concludes with a portrait of Muholi herself. Unlike the other portraits, which appear to be congruous with a specific narrative, her self-portrait presents an optical illusion of the leopard-print shirt she is wearing against a leopard-print background. It positions Muholi as an authoritative voice but also as a subject – which, like her work, raises a larger question about her intended audience.

In other words, given the celebratory and educational context of the book, one has to wonder: On whose shelf will this publication eventually end up?