Paradigm shift: After FW de Klerk announced the unbanning of the ANC

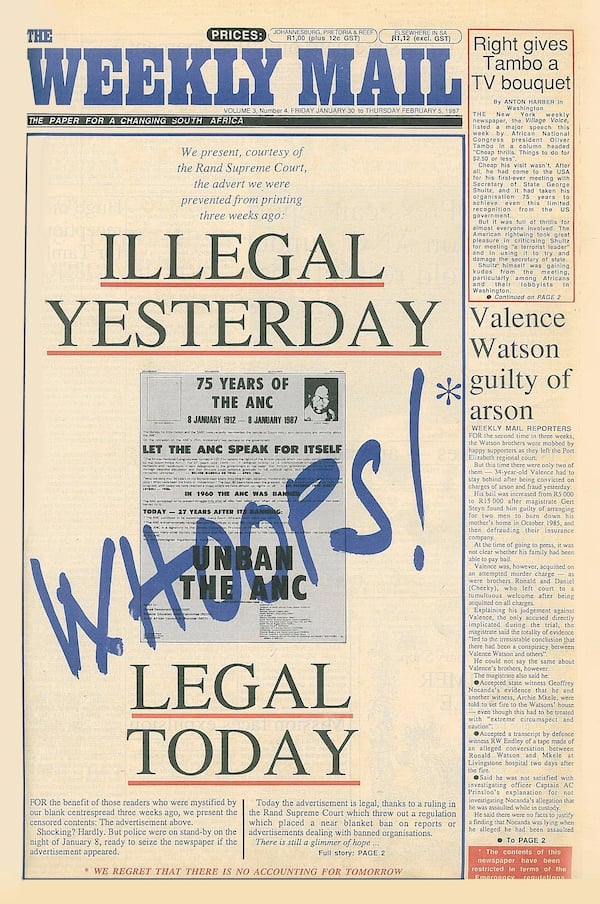

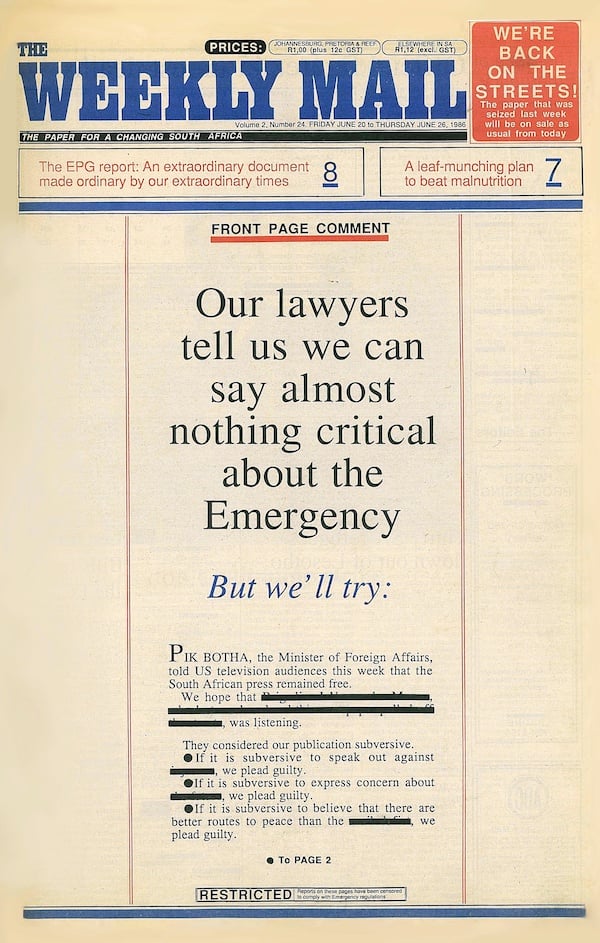

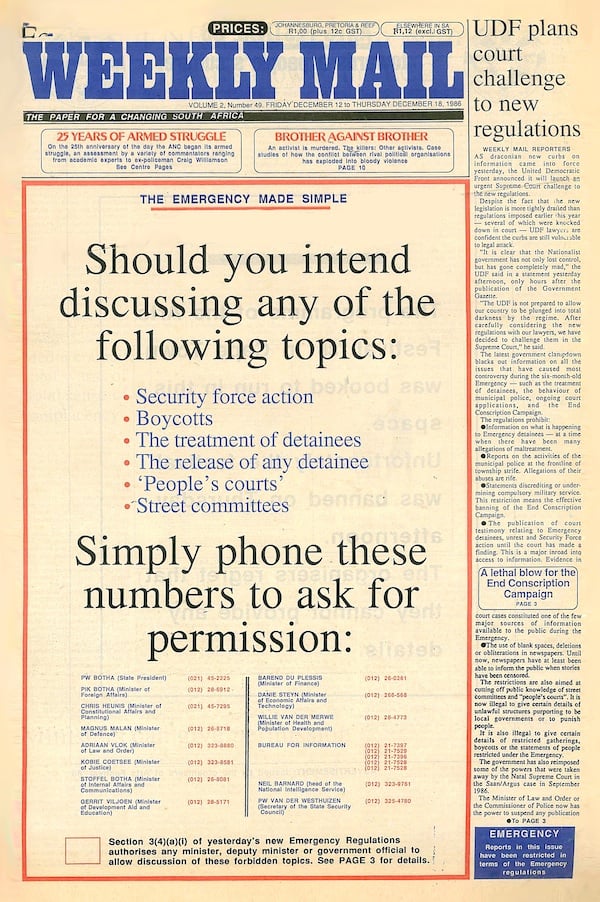

One day we were working at the Weekly Mail (now the Mail & Guardian) under the most severe state of emergency censorship, the next day we could do what we liked. One day we were preparing for court cases where we faced up to 10 years’ imprisonment for breaking the regulations, the next day all of these charges fell away and we were covering the biggest – and most challenging – story of our lives.

One day we were trying to sneak pictures of the jailed Nelson Mandela, the next day there he was on the streets of Cape Town. One day our newspaper was defined by a cause – the release of Mandela and the unbanning of the ANC – and the next day that was history. One day we were the “radical” or “alternative” press, and the next day our views were so mainstream that they were routine and dull.

The unbanning of political parties and the subsequent release of Mandela 25 years ago turned our journalism upside down in ways we did not anticipate.

Perhaps we could have. All the signs were there that something was coming in early 1990, but – hard as it is for a journalist to admit it – we missed it. We were too sceptical to buy into another set of promises that the apartheid government was capable of real reform.

The political rumour mill had been buzzing with speculation that president FW de Klerk’s February 2 opening of Parliament speech would be ground-breaking, but we had heard it too often before. This one, diplomats assured us, “would not disappoint”.

Our own newspaper reported that there was still a furious debate in the National Party between those who wanted to see Mandela released, and those who were bitterly opposed to it. We – along with most of the international media – assumed that, as always, the conservatives would win and the speech would disappoint.

Just weeks before, Mosiuoa “Terror” Lekota, then a leader of the United Democratic Front (UDF), had bet me a bottle of whisky that Mandela would be out within six months. I had heard too many UDF speeches in which any action of the apartheid government was “the last kicks of a dying horse”; I thought my bet was safe.

Most journalists watched De Klerk’s speech with low expectations. The foreign media was here to cover the ongoing township uprising, and this was what we specialised in reporting. Another speech, we believed, was unlikely to deliver progress.

Fortuitously, our senior political reporter Gaye Davis had gone to Lusaka a few months earlier to undertake the risky business of reporting from the ANC headquarters in exile in the days when it was still illegal to quote ANC leaders or do anything that could be interpreted as furthering their aims.

When we ran out of money to keep her there, she said she had to stay. She said something was happening. She slept on comrades’ couches and scrounged meals to stick with the story. We grew increasingly frustrated as she had nothing much to file for the paper, but she continued to insist that a big story was afoot.

Even then, we were locked so tightly in our mind-set that we could not read the signs. We could not imagine a breakdown in the apartheid machinery.

We could not have been more wrong. As the speech unfolded on the Friday morning, it became clear that De Klerk was going all the way: freeing Mandela immediately, unbanning political organisations forthwith, lifting all the restrictions on political activities from that day, and setting the grounds for negotiations.

His speech was explicit, clear and unequivocal and by the end of it we lived in a different world. He had torn down our own Berlin Wall.

The media world lit up. Our phones started ringing. Everyone wanted to know how and when Mandela would come out. How would he be received? Would it be peaceful, or would it add fuel to the township fires?

In the next few days, foreign media poured into the country in greater numbers than ever before, many of them flowing through our offices. We immediately started preparing a special Mandela release edition, focusing on the demands of immediate coverage and with barely enough time to understand what was happening to us.

From Davis we wanted to know what the ANC in Lusaka was going to do, because now we would be able to quote them without difficulty. But they were in their own spin and few people had anything coherent to say to her at the time.

Nine days later, we gathered on the Sunday morning to watch Mandela’s release on television and scrabble together our special edition – the first time we had done a second paper within a week.

In his history of the newspaper, You Have Been Warned … (Viking, 1996), founding co-editor Irwin Manoim described how we had to borrow a television to watch the release. It had been a point of principle to avoid the propagandistic SABC, so we did not even have a set in our shabby newsroom in downtown Johannesburg.

But this day a TV was hastily brought from someone’s house, connected and propped up precariously by telephone books.

We had come in on the Sunday to start preparing a special edition. We gathered around the television, infuriated by the SABC’s inane and bumbling coverage: they couldn’t identify the key resistance leaders because they had never covered them properly and the announcer – used to having his script handed down from above – was unable to talk through the biggest news event of his life.

We were trying to spot Mandela, uncertain when he came out whether that person with Winnie Mandela was actually him.

After he climbed into a BMW, the advertising manager at the time, Marilyn Kirkwood, who had worked tirelessly for years to get mainstream business to buy into a cheeky, outspoken, risqué, alternative paper, shouted: “Let’s call BMW for an advert!”

It was a new era. And finally it was dawning on us.

South Africa had long been a major international story and had attracted many of the best foreign correspondents, but now the numbers were unprecedented, all fighting to see and interview the man. They camped outside his Soweto family house.

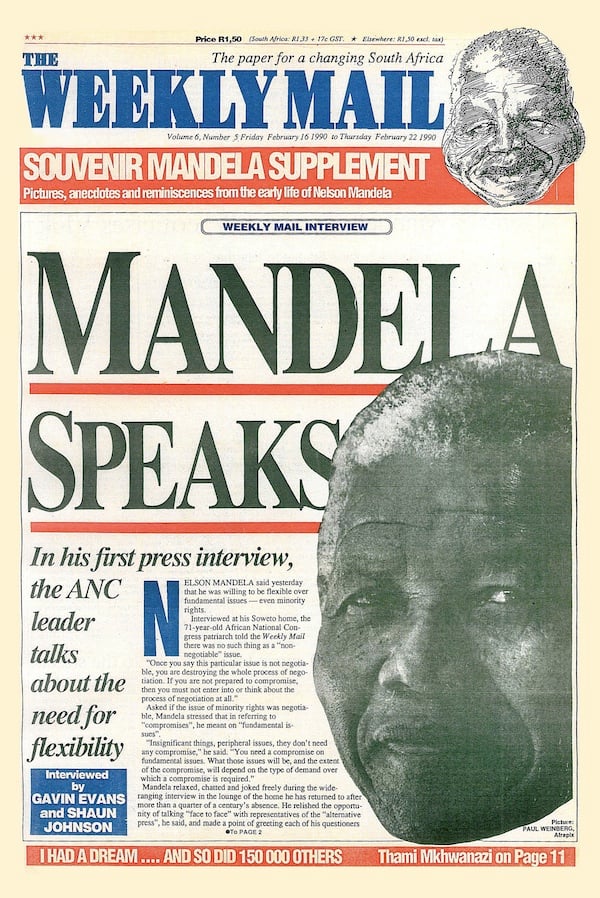

Mandela’s media gatekeeper was Zwelakhe Sisulu, editor of our sister paper the New Nation, and a long-standing colleague. He promised to look after us, but it was a harrowing week, with everyone jostling for access.

Four days after his release, within hours of our deadline, Sisulu phoned and told us to come. Of course, everyone wanted to go, and in the end five of us did, a photographer and four reporters; far too many, but there was no time to sort it out. Manoim, who had not been known to leave the office in five years, even joined in the chance to shake Mandela’s hand.

We perched on a couch in his small house and, trying not to be too awestruck, took turns to throw questions at him.

“In his first press interview,” we reported the next day, “the ANC leader talks about the need for flexibility.” It was a different tone to his tough release speech. This was Mandela delivering a carefully crafted message, rather than the committee-vetted speech he had given on his release. He would even be flexible on minority rights, he said, moving quickly and typically to allay white fears. There was “no such thing as a nonnegotiable issue”, he said.

It was the beginning of the Mandela era and the paper’s sales were soaring.

Within a few days, the mass of foreign correspondents went home. The big story gave way to long and complex negotiations and it was much harder to sustain interest. Now we really were facing the biggest reporting challenge of our lives. Negotiations were slow, tedious and detailed.

We were used to covering the action of township protests and riots – not dragged-out backroom politics. Our world had been one of good and evil, of black and white, and there was no doubt in our minds which side we wanted to be on.

But the transitional period and the long haul of negotiations required more subtlety and nuance to capture the complexity of the process. We needed new approaches to different kinds of stories, and we had to expand our coverage into new areas.

Initially, we thought this would be the Weekly Mail‘s time. We could move from the alternative to the mainstream; our friends and allies were going to be in positions of power, giving us an access we had never had; advertisers would cease to be scared of us; and – best of all – we could report without having to constantly work out how to say what we wanted to say without drawing police attention.

But we were like a rabbit in a car’s headlights, frozen stiff: we had so many options, it was all so shocking, that we were not quite sure what to do.

Indeed, the emergency media regulations fell away and the censorship laws fell into abeyance. All our outstanding court cases – about 10 of them, all related to breaking the State of Emergency regulations, each of them carrying a potential 10-year sentence – were dropped. The laws remained on the books, but nobody was paying any attention to them. It was a window of remarkable freedom, when there were in effect no restraints and we had more space to report freely than we ever had before and since.

We had to reinvent our journalism, or perhaps relearn it.

Under a state of emergency, one operates in a certain way, shaped by a contemptuous attitude to the law, when one is using one’s energies trying to get around the law to report what one can.

We had the habit of reporting with attitude on authorities that we considered illegitimate. What was the right attitude to adopt now during an interregnum: when the government still was not legitimate; their opposition was just finding their feet back home; and the nature of the new order was not yet clear?

The old was dying, but the new was not yet in place, and that made it a time of unpredictable uncertainty.

We had asserted our independence in relation to the ANC and its internal allies a while earlier in tackling the tough Winnie Mandela football club story, much to the consternation of some who had expected uncritical loyalty.

But what was our role in a period of delicate and difficult transition? Should we give them an easy ride, knowing the difficulty of returning from exile and then simultaneously negotiating and preparing for government? Or should we now treat them like any other contender for power, fair game for our scrutiny and criticism?

Did one want to be close to the next government, or did one want some distance?

Many of our staff, particularly younger reporters such as Mondli Makhanya and Ferial Haffajee, were locked in debate about whether, as journalists, they should join the ANC or stand aloof from what was to become a grand political tussle. What were their moral obligations to the cause of liberation, and would they serve it better as activists or journalists or some combination of the two?

What would produce the best journalism?

This period ended with Inkathagate in July 1991, when – working with David Beresford of the Guardian – we exposed the illegal security police support for Inkatha.

It was a critical political moment for the country, and it was when the newspaper found its voice again: making its own news by investigating and exposing wrongdoing wherever it was to be found.

It was the best-known story of the time, but it was only one of a series that exposed De Klerk’s government’s attempts to undermine the ANC during the negotiations. It set a new tone and established a new role for the paper.

Anton Harber is the Caxton professor of journalism and media studies and director of the journalism programme at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg