Land reform can assist in creating more employment-intensive farming systems.

“It’s perfect in summer, when it is too warm. In winter I drink coffee.”

Marie Syster is boiling a battered silver kettle over a gas cooker. It begins to whistle inside the mud hut. “Rooibos maak die wêreld beter [Rooibos makes the world better].”

Taking two tea bags out of a small tin, she drops one each in two yellow enamel mugs. No milk. No sugar. At 5am the room is vaguely lit by the coming sun. This is the tiny village of Melkkraal; there are about 10 zinc and mud houses, about 400km north of Cape Town.

The hot tea sits for a few minutes, steam rising off the mugs. Syster picks up her mug and sips slowly. “Ja. Dis perfek.” Wearing an oversized grey shirt and jeans, she picks up a glass 1.25 litre plastic bottle, half-filled with water and starts the 20-minute walk to the west of her home, where the rest of her village has begun picking the red tea.

The tea was the special treat of Bushmen living along the eastern coast of South Africa, who crushed and chewed it. Now it is boiled. It apparently eases eczema and asthma. The sweet taste and mahogany colour have made it an export hit. Melkkraal is the northernmost part of the only growing area in the world.

‘Bulb capital of the world’

A fifth of the country’s rooibos comes from this district. The farm was founded in the mid-1800s when a Dutch settler married a local woman and they started growing sorghum. This is in the area known as the Namaqualand and is famous for the flowers that carpet the veld in spring. Nieuwoudtville has one main tar street. A sign proclaims this to be the “Bulb Capital of the World”. There is a thin layer of grey sand over the sedimentary rock, and only fynbos and some aloes can survive in this semi-desert.

The 20 residents survive by picking organic rooibos and selling it to a co-operative called Heiveld, which they helped to found. About 200 tonnes a year are exported to Europe, mainly Germany, earning R4-million last year.

The farmers set up the co-operative in 2001, and the R4-million is shared between 73 farmers who must pay staff and production costs, and ensure their harvest reaches the Cape Town harbour.

Rooibos tea is shredded and laid out to dry on one of Bloemfontein’s tea courts. (Photos: David Harrison, M&G)

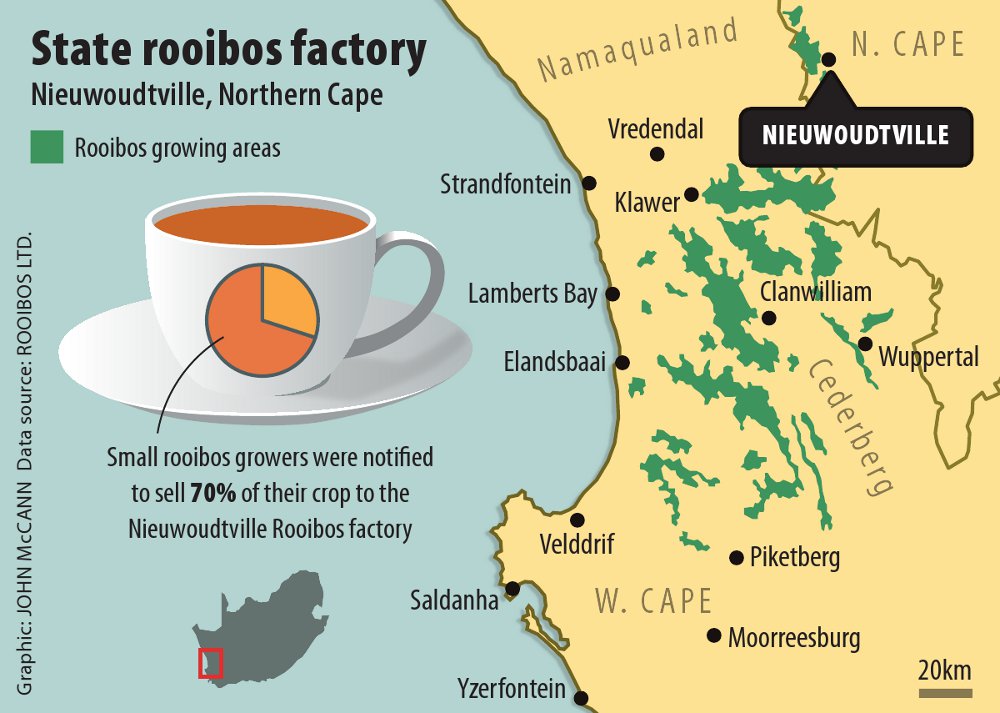

The farmers are also able to charge a premium for their organic tea, but in 2008, the provincial agricultural department, in an “empowerment scheme” for “previously disadvantaged farmers”, built a rooibos production and packaging plant in Nieuwoudtville.

The tea packed in the department’s Nieuwoudtville Rooibos factory is not organic, and now the farmers say they are being forced to sell their crop to the factory and not to their co-operative.

If they don’t give at least 70% of their crop to the factory, the farmers say their tractor, tools and diesel, donated to them by the provincial department, will be taken away.

“This land is perfect for rooibos. It is at home here,” says Katerina Kotze. The 61-year-old lifts her blue dress as she walks so that her worn leather boots don’t get caught. Their field of rooibos is on the side of a dry river bed.

Tea court

The young men work at what they call the tea court, feeding the leaves into a threshing machine and then drying and packing the tea into 17kg sacks. The older men cut leaves from the bush. By 6am the heat is building, and everyone is sweating. Rooibos is harvested in the summer months and work stops at midday because of the heat. Those harvesting the leaves wear thick jeans or overalls.

Andries Syster, bent double, wraps his palm around a clump of the reeds, and twists them away from him. He quickly flicks the sickle towards himself, severing a handful of leaves. There is a strong smell of fresh rooibos. He leaves 10cm of the stem in the sandy earth, which will grow into next year’s harvest.

He passes the clump to Kotze, who is following close behind him. She ties it into a bundle, and they move on down the field.

In 1999, the Melkkraal residents joined other poor farmers to create Heiveld. Sitting at a small wooden table at the Heiveld offices, general manager Alida Afrika says last year the co-operative won the Equator Prize for sustainable land management, an initiative by the United Nations Development Programme.

She says the farmers have to follow a strict planting system to keep their organic certification. This requires organic seeds. Last year the competing rooibos factory started giving farmers chemically treated seeds.

Organic status

Planting these in any field means the rooibos cannot be sold to the lucrative organic market, and it takes at least three years for the fields to recover their organic status. The Nieuwoudtville Rooibos factory also sent a letter to each of the historically disadvantaged farmers in the area, only seven of whom are not members of Heiveld.

The letter, in Afrikaans, told the farmers that those who had benefited from the agriculture department would now be required to sell the factory 70% of this year’s harvest. Those who didn’t would lose farming equipment.

The department, in what it calls the “implementing plan” for the factory, says local farmers were receiving “ever decreasing support” and more resources were being made available to the more developed Western Cape rooibos market. One of the factory’s objectives was “empowerment of rooibos tea planters, especially the emerging farmers”.

The plan, from 2008, says 49 commercial and 41 emerging farmers in the Nieuwoudtville district had agreed to supply rooibos to the factory. The plan says that most of the emerging, or historically disadvantaged, farmers were already part of Heiveld but does not say how to get them to sell to Nieuwoudtville Rooibos. In a meeting in October 2014 with Phemelo Kegakilwe, the acting chief director of the provincial agriculture department, it emerged – according to minutes the Mail & Guardian has seen – that the tractors had been registered in the name of Nieuwoudtville Rooibos. Kegalikwe said this was a mistake and registration should be in farmers’ names.

Afrika says of the contents of the letter that this is tantamount to bullying. “Many of the farmers are illiterate so did not know what they were agreeing to. And then you threaten them with losing their tractors and diesel. That’s not right.”

‘Private company’

The government was doing the opposite of what it should, she says. “This is not giving a better life for all.” Heiveld does not force farmers to sell to it, she says, and this means they are free to sell to Nieuwoudtville Rooibos. “We tell farmers to not put all their eggs in one basket.”

But this means the collective faces problems in meeting orders if people sell elsewhere or start planting chemically treated seeds.

A call to the Nieuwoudtville factory was answered by a man who said: “It’s a private company. That’s all I am willing to say.”

Heiveld general manager Alida Afrika says government took advantage of the rooibos farmers’ illiteracy.

Nieuwoudtville Rooibos is listed as a (Pty) Ltd company, with a board of directors who each have a share. But court documents – from when the factory was taken to court for unfair dismissal – say: “The whole project has been funded exclusively by the department of agriculture of the Northern Cape.”

In its 2011 provincial budget, the factory is listed as having received R160-million and as being one of its two flagship programmes, funded through the Letsema grant for poverty reduction.

Government competition

At Heiveld’s tea court, 50km down a gravel road frequently punctuated with cattle gates, Gerrie Koopman gives a sad shake of his head when asked about the other rooibos factory.

“It is a huge problem to have government competing with us. They have unlimited funds backing them.

“Organic production is so good. It creates jobs and it means we see the money for our work. Before we worked and barely survived,” he says.

Koopman, a thin man with a shy smile and tight-fitting glasses, took over the family farm in his late teens after his father died. His great-grandfather purchased it in the late 1800s, when a change in legislation allowed coloured people to buy marginal land. His first memories of rooibos where when it was mostly produced by hand, with the twigs being cut off so the leaves could be chopped and bruised on a wooden block. After fermenting in the sun the mahogany-coloured tea would be drunk, or sold locally.

“But during apartheid the farmers could only sell to the large-scale white farmers, who controlled the price. After that it was companies controlling the price,” he says. “This is the first time we control our lives. It feels good.”

The government factory is threatening that.

“We worked so hard to get this and just as we are growing they want to destroy it,” Koopman says.