At last count

A financial black hole of growing proportions is engulfing Eskom as it dances between blackouts and load-shedding.

The utility claims that maintenance issues are the principal reason for the current shortfall of electricity, but it is delays at the two power giants that is costing it, and the country, dearly.

Its failed bet that Kusile and Medupi, which are four years behind schedule, would already be on line means the utility is not earning revenue from the two giant nonstarters and has to fund the stratospheric capital and interest cost itself.

Eskom has acknowledged that the delays mean that 5 000 megawatts – roughly the amount that each of the two plants will be able to produce when they are operational – is not on line. This amounts to an estimated annual loss of R30-billion from electricity sales.

Eskom is coy about the mounting interest bill on servicing the capital cost of the two power stations. Energy analyst Chris Yelland said the interest bill for Medupi was estimated at R29.2-billion and for Kusile at R48.7-billion, but these figures were given to him six months ago but at that stage were already outdated.

“The longer the delay, the higher the interest bill goes,” he said. “These need to be updated but Eskom appears very reluctant to provide these figures.”

Coal costs

There is also the cost of coal contracts that, in the case of Medupi, have already kicked in. Exxaro disclosed that this amounted to R1.6-billion in 2013.

According to Eskom’s integrated report for the six months ending September 2014, debt securities and borrowings totalled R265-billion, up from R182.5-billion in March 2012.

Had the two new power stations come on line in 2011 as was originally intended, many of Eskom’s woes would have been averted.

In a bid to keep the lights on in recent years, the utility neglected the maintenance of its power stations, and says it needs breathing room of about 5 000MW (an eighth of its current installed capacity of 40 000MW) to perform planned maintenance without the risk of load-shedding.

Had the new build gone to plan and brought on the 4 764MW Eskom says would have been on line today, this would not only have created the breathing room it needs, it would have generate R30-billion a year, calculated at a current tariff of 70c a kilowatt an hour, if one assumes the stations would run at 100%, according to experts.

Interest bill

The interest bill is a number much harder to extract from the black hole, thanks to Eskom’s reporting methods and apparent unwillingness to provide more detailed information.

When asked: “What is the total interest bill projected to be for both Kusile and Medupi?”, Eskom replied: “The cost of capital for the projects forms part of the estimated cost of the project.”

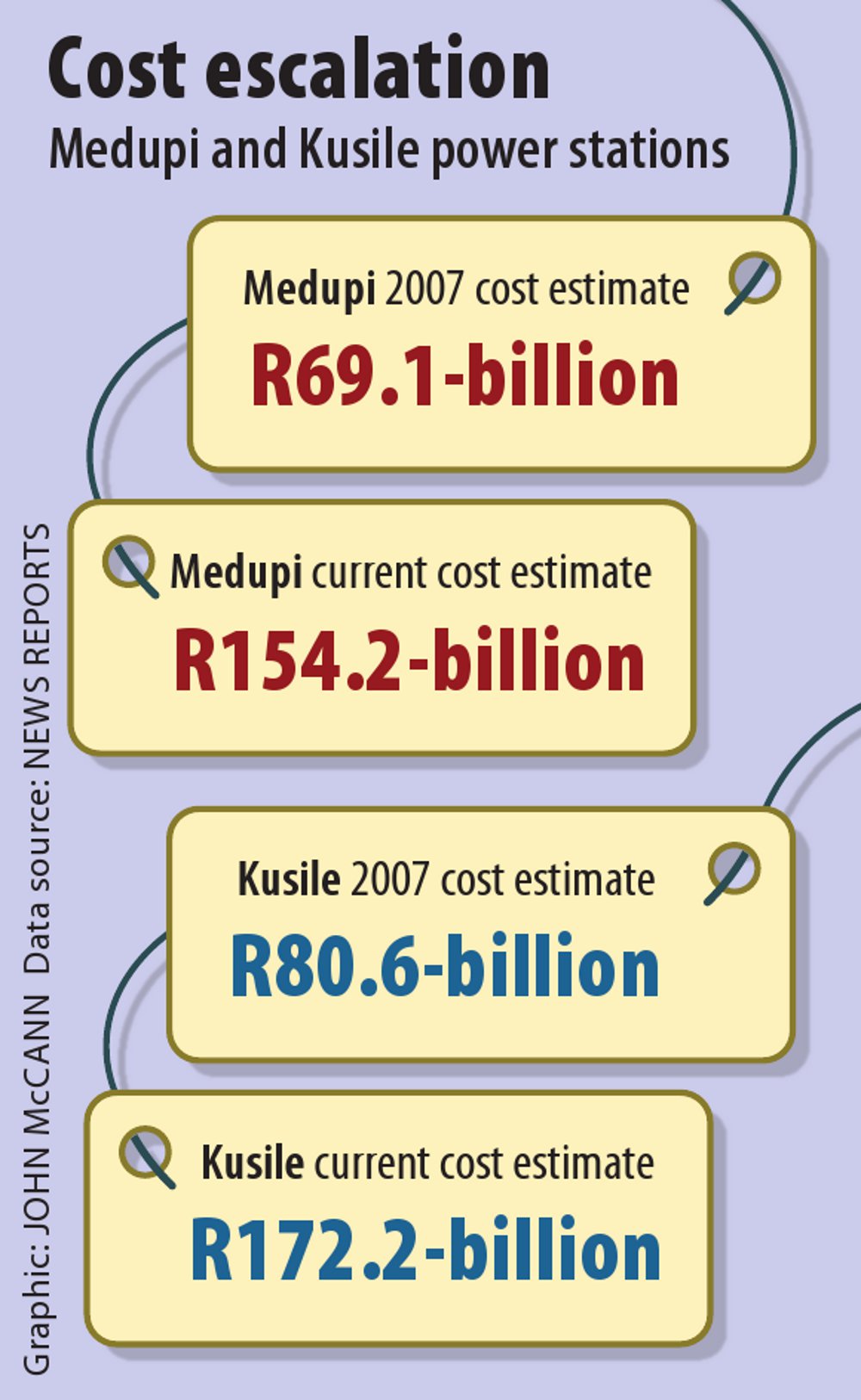

The costs of Medupi and Kusile were initially estimated at R69-billion and R80-billion respectively. But the latest (outdated) estimates have risen to R154-billion for Medupi and R172-billion for Kusile.

Three independent industry experts insisted that the interest costs were not included in the cost of completion of the two projects.

“Because the cost is not ring-fenced, it is difficult to get a grip on it”, said Yelland. “But added interest during construction can easily account for 25% of the construction cost. It’s a huge cost because Eskom is using borrowed money, not equity.”

“The only thing they [Eskom management] will talk about is overnight costs [this excludes interest],” said independent power consultant Doug Kuni. “They do not disaggregate it. Eskom does its financial accounting specifically in this way so they are not open to scrutiny … It’s easier to stir it all up and ask the regulator for more revenue.”

Power station debt

Asked how much debt the utility had incurred to fund the two megaprojects, Eskom could not provide a separate number from its aggregate debt of R265-billion.

“Eskom follows a ‘pool’ approach to financing the utility’s requirements. This pool of funds are made up of cash generated by electricity sales, bonds issued to the markets, specific loans linked to trade finance, etcetera,” the utility said. “All these sources of finance make up the overall cost of capital of Eskom. The Medupi and Kusile projects are allocated their fair share of this capital costs of the ‘pool’, while the project is still under construction.”

Debt-servicing costs have grown too and, according to Eskom’s annual reports, interest paid more than doubled from R4.2-billion in the 2008-2009 financial year to R9.9-billion in 2012-2013.

Moreover, Medupi and Kusile are subject to contractor claims that result from a range of things such as variations or additional standing time for delivery trucks.

Last July, Eskom said it had received cumulative contractor claims at Medupi and Kusile worth R50-billion, as reported by Engineering News. But the group executive for the capital division at that time, Dan Morokane, said global settlement rates were typically between 7% and 9% of the original value claimed because of duplications.

Eskom is also paying penalties to Exxaro because coal was supplied for Medupi, but the power station is unable to use it.

Confidential information

As reported by the Mail & Guardian in March last year, the coal supply agreement caters for the shortfall payment of R1.6-billion in 2013 and R352-million in 2012. Asked for further information about the costs associated with this agreement, Eskom said: “The content of the coal supply agreement cannot be made available due to the confidentiality of the commercial considerations.”

Eskom could not provide information on a coal supply agreement for Kusile and industry experts are un-aware that one is in place.

Because of the power crisis, Eskom has to run open-cycle gas turbines, which guzzle diesel at a rapid rate for extended periods. The utility says it spends about R1-billion each month on diesel.

Commenting on the treasury’s rescue package for the utility, which involves an access to further government guarantees and the sale of assets to provide Eskom with a cash injection, Kuni said the ministry of finance was taking quality, money-yielding assets and “throwing it into a big black hole that is Eskom … You don’t know how big the hole is, so why would you put money in it?”

Kusile power station a source of grievance for local residents

Driving along the N12 to Emalahleni, Eskom’s wannabe power station, Kusile, stands alone on the hazy Mpumalanga horizon looking decidedly incomplete. A number of big red and yellow cranes are perched, motionless, above the concrete structure.

Across the highway, fumes billow from the Kendal power station that was completed two decades ago.

But turning into the road that leads to Kusile (which translates as “dawn has come”), activity picks up as trucks and vehicles of all kinds whizz up and down at speed. Blasting at a quarry site sends gravel, to be used for concrete for the mammoth structure, flying metres up into the air.

Like its more famous sister station, Medupi, Kusile is at least four years delayed. According to comments in November by Eskom’s then acting chief executive, Collin Matjila, the rush to get Medupi’s first unit on line had seen a reallocation of resources to this cause at the expense of progress at Kusile.

“I came here when there was nothing,” said one quarry worker. He was hired in 2009 and his contract ends in 2017. Asked whether he is hopeful his contract may be extended, he shakes his head. “I think it will be finished.” His colleague agreed. “Yes, it must be finished.”

Medupi has been plagued by work stoppages, but also by disgruntled locals who are unhappy about contractors bringing in labour from elsewhere.

At Kusile this also seems to be a key grievance. In the nearby town of Phola a woman wishing to be known only by her first name, Athalia, said she had seen no benefit from the construction. “There has been niks change. Kusile doesn’t hire our children. There are people here from Natal.”

Her friend, Maria Mokoena, concurs. “It’s the people from outside, they get the job. Our children study physics and maths, but now they need the experience.”

Eskom said Kusile has more than 17 000 people working at the site, 8 000 to 9 000 of whom are from surrounding areas. Mokoena said some locals had been employed by the project, but the higher-ranking positions were reserved for labourers from Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal.

Clinics and schools were filled to capacity, she said.

George Norman Maseko came to Phola in the hope that Kusile would result in a job. Instead, he helps his friend alongside a road to sell and repair tyres. “Even today I went up there, looking for a job,” he said. It’s the second time in a month.”

Eskom said the project had reached its peak in terms of employment numbers and had no additional employment opportunities.