Sedibe was abducted from Swaziland by the security police in 1986 and taken to Vlakplaas

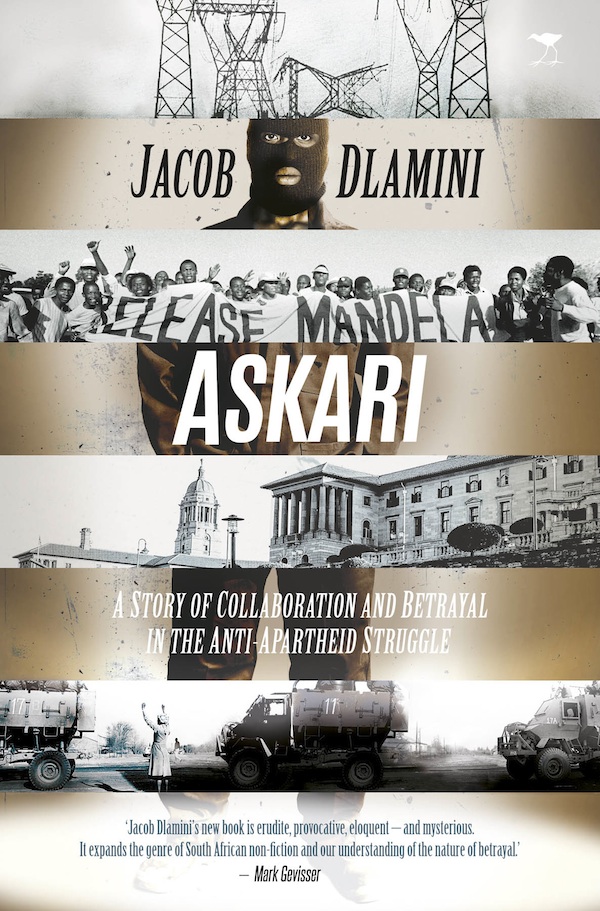

Jacob Dlamini’s book Askari: A Story of Collaboration and Betrayal in the Anti-Apartheid Struggle purports to tell the story of “Mr X1” or “Comrade September” – Glory Lefoshile Sedibe – who converted from “freedom fighter to apartheid agent”, as vividly witnessed when Sedibe testified against his former ANC comrades in a terrorism and treason trial in which they faced the death penalty.

Dlamini writes that the word “askari” entered the South African lexis to refer to “ANC and Pan Africanist Congress members who, through voluntary defection or torture, had switched sides to fight against their former comrades as part of a counterinsurgency campaign”.

Sedibe joined the ANC at the age of 24 in 1977. He left the country “heartsore” after his brother was sentenced to five years in prison in 1976 for organising a pro-Frelimo rally celebrating the collapse of Portuguese rule in Africa. Sedibe crossed the border to Swaziland as a refugee and “had yet to turn 25 when the ANC sent him for specialised intelligence training in East Germany”. He was abducted from Swaziland by the security police in 1986 and taken to Vlakplaas, the police farm west of Pretoria where state security assassin Eugene de Kock was based.

Dlamini quotes a 1984 Umkhonto weSizwe manual explaining forms of torture favoured by “South African agents”, which recognised that “people always broke under torture; that they always talked”. It is reported that Sedibe tried to escape but failed and that “De Kock’s men had slaughtered a sheep and were barbecueing on a spit outside as the white cops took turns torturing Sedibe”. He was apparently assaulted and force-fed alcohol, and eventually talked during three months of interrogation. He was “given a ‘choice’ that was not a choice: talk and live, or refuse and die”.

The information Sedibe gave is said to have led to the ANC in Swaziland being wiped out; he helped catch and recruit key ANC members. After being “turned”, Sedibe worked as a policeman – because if he returned “the ANC would kill him for treachery” and if he left the police “De Kock and his men would kill him for desertion”. Yet, said De Kock, Sedibe “never changed his pro-ANC political views” and gave only 10% of what he knew – just to stay alive.

According to Dlamini, Sedibe was not a victim but had “agency”. He maintains that “we cannot accept Sedibe’s claim he had no choice” or “limit our attempt to understand why some became askaris in the torture chamber”.

What’s striking about Askari is the absence of the subject’s voice. Save for a short passage in which Sedibe explains “betrayal” during a 1988 trial, he is almost silent. There is an overemphasis on and glorification of European and Latin American experiences; links to experiences in African countries and the civil rights movement in the United States are scant.

Dlamini downplays racialised violence, torture and the decisions (not choices) black people like Sedibe had to navigate for the sake of their lives and livelihoods. There is a misguided masculinist tendency to see violence in corporeal terms – there must be a body, or it’s not violence. “One needs only to compare the numbers of people slaughtered by the Argentine and Guatemalan juntas … with those killed by successive apartheid governments over 40 years to realise that, as criminal as apartheid was, as a killing machine it was no match for the murderous regimes found in Latin America.”

Then there are problematic statements such as “black education in fact boomed under apartheid”, “for most black South Africans, the face of apartheid was black” and that there were “thousands of black policemen and soldiers” – although he contradicts this when he says a 1993 report noted only “103 South African and 14 Namibian askaris”.

Of Penge mining town in Limpopo, Dlamini says white miners lived in “white square” houses with gardens, street lighting, recreation centres, a hospital and trading stores – and the black area had none of these facilities. Yet despite this, “Sedibe had a happy childhood” growing up there.

Social scientists have long called for a widening of conceptions of violence to encapsulate structural violence, which, anthropologist Paul Farmer notes, includes “a host of offences against human dignity: extreme and relative poverty, social inequality ranging from racism to gender inequality, and the more spectacular forms of violence that are uncontestably human rights abuses”.

Askari is strongest when it shows apartheid’s psychosocial impacts. Sedibe died in 1994, possibly from alcohol poisoning: he was chronically depressed and “drinking about three 750ml bottles of vodka a day”. This is true of many askaris, who escaped from their horrible lives as apartheid “hostages” by indulging in casual sex, marijuana and excessive drinking.

Sedibe was not a citizen who woke up one day and decided to help the apartheid government. His is a story of torture, violence and assassination.

American academic Saidiya Hartman reminds us that “consent is meaningless if refusal is not an option”. Cultural critic Henry A Giroux says terrorist states individualise “fear and insecurity”, undercutting “the formation of collective struggle”. He says this “fear of punishment, of being killed, tortured or reduced to the mere level of survival [becomes] the government’s weapon of choice”.

Dlamini’s conclusion – that Sedibe “was a moral agent who made informed choices along the way” – is a form of violent erasure. Poor analysis, the lack of a subject voice, unsupported problematic statements and the erasure of apartheid violence spoil the book.

Gcobani Qambela is a lecturer in social anthropology at North-West University in Potchefstroom. Askari is published by Jacana Media.