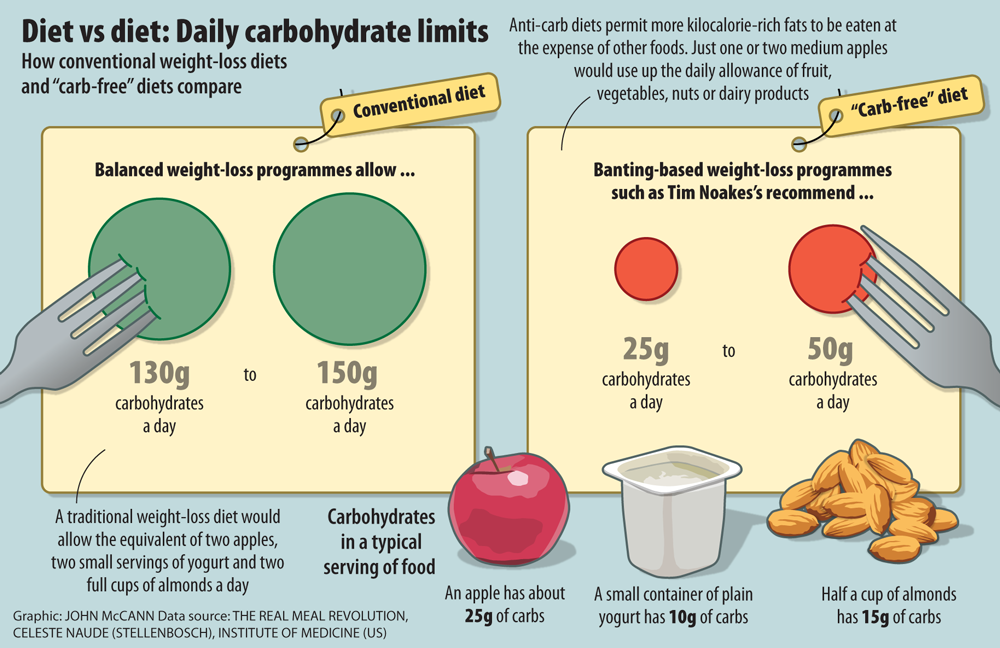

Lifestyle: Tim Noakes’s book recommends that carbs should be limited to between 25g and 50g a day.

Laetitia Vermeulen* slowly closed her white muslin curtains. Tightly, until she was sure no one could see inside. It was around 9pm.

She lit the fireplace in her living room, and poured herself a double Irish whiskey, on ice.

She walked to the DVD player to insert the first disc of series seven of police drama series Criminal Minds. She had the next eight episodes stacked nearby, in the correct order.

Earlier that afternoon Vermeulen had calculated exactly how much time she’d need to view the DVDs: six hours, or nine 40-minute episodes.

Tonight the loneliness was so deep it was “breathing” in her ears.

She cradled her sausage dog, Otto. Together, they lay on the couch, under a light green blanket.

As the first instalment of Criminal Minds appeared on her wide plasma TV screen, Vermeulen (34) stretched an arm out, hardly looking, towards the first of 10 bowls arranged in two equal rows on the coffee table in front of her.

Number one would be the chow mein – one of her favourites. She filled her mouth with the first morsels of the Chinese takeaway of succulent fried chicken, noodles and vegetables. Otto got a small chunk as well.

As she ate, Vermeulen’s eyes did not leave the screen. The food pacified her, although she knew it was providing only temporary relief.

Before the first episode ended, she began eating the second bowl: a mixture of Bubbles chips and Sweet Chilli Pepper Doritos. Fifteen minutes later, she took another sip of whiskey and inserted the second DVD. “Time for a short break from eating,” Vermeulen told herself.

But she couldn’t stop. She scooped the last few chip fragments into her mouth as her “secret addiction” took over.

Now for the Strawberry Whirl biscuits. As she continued to eat, she refilled her whiskey tumbler and returned to viewing Criminal Minds while consuming the last two bowls in the first row of “treats” – speckled chocolate eggs and Marcel’s English Toffee frozen yoghurt.

Vermeulen’s loneliness began to fade.

Staged photo

Staged photo

Round two

The second row of food beckoned: bowls of Big Korn Bites, Cheese Naks, Gino Ginelli Choc Milano ice cream, chocolate mousse and a sushi smorgasbord. And when the bowls were empty, four slabs of chocolate – a Milky Bar, Top Deck, Bubbly and Aero – were waiting in a neat pile.

Vermeulen always ate at the same time – from 9pm onwards – and in the same way: the foods, the brands and flavours were always the same; they were eaten from the same containers and in the same order.

It had to be that way; it didn’t feel right otherwise.

Six hours was almost exactly the time she needed to eat it all plus the top-up supplies; the leftovers in the packets and containers, such as the 1.5-litre ice cream tub and large packets of chips, from which each bowl was filled – which she kept in her kitchen.

She had timed it before, meticulously.

Shortly before 3am, the final episode of Criminal Minds concluded. Vermeulen had finished all the food, except for a few stray chips.

Mission accomplished.

Exhausted, she fell asleep on the couch, arm around Otto. She didn’t bother turning the TV off.

Hours later the first rays of sun awoke her. She ambled to bed, waves of intense guilt and self-loathing engulfing her.

At two in the afternoon she again awoke, to her customary “heavy hangover”. Nauseous. Every bit of her mouth covered with fresh, raw sores. Eyes so swollen she couldn’t see properly. Hearing temporarily impaired. All sensations and symptoms she was used to.

“People don’t realise what binge eating can do to you,” Vermeulen says while staring out the window of a therapy room at the Harmony Addictions Clinic in Hout Bay, near Cape Town. “You can literally eat yourself to death.”

In August 2014 Vermeulen was admitted as an inpatient to the clinic’s Harmony Eating and Lifestyle Programme (Help). It treats overeating and obesity as an addiction, using sports scientist Tim Noakes’s controversial low-carb-high-fat Banting diet.

By this time Vermeulen had tried every diet she’d heard of. Some worked, in the short term, but she would always regain the weight she’d lost. She would stay at the clinic for 21 days, for which her medical aid paid R22 000.

On admission the 1.62m-tall Vermeulen weighed just short of 100kg. Her body mass index, or weight-to-height ratio, was 37.3, which made her an “obesity class 2” case (the second-worst form of obesity), according to the World Health Organisation’s weight classification system.

Vermeulen’s binge-eating episodes were happening almost every second night. She no longer accepted invitations from her friends to social events. She didn’t open her mail and regularly didn’t turn up for work.

“Eating was so much nicer,” she says. “There’s a saying that says shit stinks, but it’s warm. An eating disorder is similar: it’s horrible, but it’s comforting.”

The Harmony Clinic in Hout Bay, Cape Town, treats overweight people by ensuring inpatients eat food that is low in carbs and high in fats.

The Harmony Clinic in Hout Bay, Cape Town, treats overweight people by ensuring inpatients eat food that is low in carbs and high in fats.

Binge eating disorder

At the clinic Vermeulen was diagnosed as being a “textbook case” of binge eating disorder, a psychiatric illness added to the American Psychiatric Association’s fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 2013. Most countries, including South Africa, use the DSM to diagnose mental illnesses.

Binge eating disorder is the consumption of unusually large quantities of food in a relatively short period of time – according to the DSM, at least once a week over a period of three months. Eating is usually done in secret and associated with “marked distress”.

Binge eating disorder is different from bulimia nervosa, which also involves binge eating episodes, in the sense that binges are not followed by purging, vomiting or compensatory use of laxatives. The United States government’s 2007 Comorbidity Survey Replication study has revealed that binge eating disorder is more than twice as common as anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, with 3.5% of women and 2% of men developing it in their lifetimes.

Studies have shown that about 65% of people with the disorder are obese, making them significantly more vulnerable to developing diabetes, strokes, heart conditions and some cancers.

At the clinic Vermeulen learned that her eating disorder was partially driven by loneliness. “It’s about feelings that you don’t know how to deal with. I’ve been single for so many years now, and have had to deal with a lot of rejection. Eating was my way of coping with my self-pity,” she says.

Help dieticians told Vermeulen “restriction” was the answer to her problem: she had to stay as far away as possible from certain foods – in particular those containing sugar and carbohydrates, as the Banting diet requires. The biological reason responsible for Vermeulen’s binge eating disorder, they said, was that she had become addicted to sugar and carbohydrates.

Sugar addiction controversy

This is in stark contradiction to mainstream science, which argues that there is insufficient proof that sugar and carbohydrate addiction exists in the same way as drug or alcohol addiction. Sugar and carbohydrate addiction are, for instance, not recognised as eating disorders in the DSM.

But Help director Karen Thomson, a rehabilitated cocaine and “sugar addict”, who has been diagnosed with binge eating disorder herself, is adamant: “Sugar and carbs hijack the pleasure centres of our brains in the same way that drugs like cocaine and heroin do. Sugar created the same addictive cycle in me as cocaine. I had withdrawals, cravings and feelings of guilt and shame. That whole addictive cycle was present for me in both those substances. Cocaine was in fact easier for me to give up because I’m not exposed to it every single day.”

According to Thompson, about 30 inpatients and 40 outpatients, mostly women, have completed the Help programme since its launch in November 2012.

The average weight loss is between 4kg and 9kg a month and cravings to binge mostly disappear. “We treat ‘food addicts’ in exactly the same way as we treat drug and alcohol addicts,” she says. “They have to abstain [from their addictions] as much as possible. They can’t have different rules.”

But Christopher Szabo, a psychiatrist in the psychiatry department at the University of the Witwatersrand, who specialises in treating eating disorders, warns: “To completely abstain from certain foods can be hugely problematic. One of the biggest triggers of binge-eating episodes is ‘restrictive’ eating patterns. Often the food that people binge on is the food that they restrict.”

Are carb cravings a red herring or is sugar addiction a thing? Read our story here.

Weight-loss results

Vermeulen’s last stage of binge eating happened a few weeks after a 600 kilocalories-a-day diet (an average person consumes 2 000 kilocalories a day) during which she lost 30kg within four months.

Says Vermeulen: “You pull that elastic tight, tight, tight … and when it shoots loose then the binge eating comes back like nothing before and you lose all control.”

Szabo maintains that “abstinence equals restriction equals potential binge eating episode. That is why when people talk about ‘food addiction’ I’m not convinced that it’s helpful, because the truth is, to restrict or to limit food is often to predispose to more problems.”

‘Sugar and carb addiction are in our genes,” says Tim Noakes, gesturing with his hands from behind his desk at the University of Cape Town’s Sports Science Institute in Newlands.

In December he retired from the university, where his peers have been extremely critical of his dietary advice. Noakes now only does part-time work for the institute and has spent most of his time this year organising what he calls “the world’s greatest gathering of international experts under one roof”: the first international low-carb-high-fat health summit, branded the Old Mutual Health Convention, in Cape Town from February 19 to 22.

He’s arranging the event along with Thomson, to whom summit press releases refer to as “South Africa’s authority on sugar addiction”. Noakes also helped Thomson to design the Help programme and to appoint Banting dieticians.

Sugar cravings and obesity

“Sugar and carbs make you hungry, so you overeat,” he explains. “They do not satiate you and drive your appetite. They cause cravings. The more sugar you have, in my opinion, the more likely it is that you will overconsume calories and get fat. Sugar, probably more than other carbs, drives that hunger and has fuelled, if not caused, the world’s obesity epidemic.”

A Washington University study published in the medical journal the Lancet last year found that the rise in global obesity rates over the past three decades “has been rapid, substantial and widespread, presenting a major public health epidemic in both the developed and developing world”.

According to the study, South Africa has the highest percentage of overweight and obese people in sub-Saharan Africa: seven out of 10 women and four out of 10 men have significantly more body fat than what is deemed healthy.

Sugar is a carbohydrate, albeit a “simple” one with simple chemical structures. “Complex” carbohydrates, such as those contained in food such as potatoes, rice and bread, are made up of long chains of simple sugars.

All fruit and vegetables, breads, dairy, beans, seeds and sugary foods contain carbohydrates, but in varying amounts.

When complex carbohydrates are digested, they are broken down into small molecules of sugar known as glucose that the body uses as energy. All types of carbohydrates therefore make our blood sugar levels rise, but sugar does so more quickly than complex carbohydrates.

Controversial: Sports scientist Tim Noakes advocates a low-carb-high-fat Banting diet to reduce weight, including that gained by binge.

Controversial: Sports scientist Tim Noakes advocates a low-carb-high-fat Banting diet to reduce weight, including that gained by binge.

Sugar ‘hijacks’ the pleasure pathways

“The thing about carbohydrates is: they make you feel good,” Noakes says. “Modern scientists have shown that there are pathways in the brain that light up when you eat sugar and it’s exactly the same pathways – all the pleasure centres – that light up with drugs or alcohol. So sugar is like alcohol or drugs.

“When carbs hijack the brain, they disrupt something called the apastat, which controls how much we eat. If your apastat is intact, you will eat exactly the right number of calories for how much energy you’re spending. It would be impossible to get fat. But if the apastat isn’t working correctly, you’ll overeat, have cravings and likely binge.”

Over the past year Noakes has delivered 100 “healthy eating” Banting-style lectures to more than 20 000 people across the country. “There’s no such thing as a healthy carb,” he cautions. “That’s why you have to avoid sugar, but also other carbohydrates.”

Noakes waves a pen in the air.

“[If you were a smoker and wanted to stop], you can’t smoke one cigarette a day – you’ll get addicted again. So for a sugar addict, one teaspoon of sugar is going to push them back to two or three. They will go and find the chocolates and so on.

“You can’t smoke a cigarette a week. You also can’t eat sugar if you’re addicted to it. For some people it’s got to be all or nothing. And if you can’t make it all or nothing, that’s a problem.”

Banting results

At Harmony Clinic Vermeulen says she shed kilograms at lightning speed. “Within the first week I dropped from a ‘tight’ size 42 to a size 38. The dietician wasn’t allowed to tell me how many kilos I had lost, so that my sole focus wasn’t just on the scale. But he was shocked at how quickly my weight was dropping.”

Vermeulen jumps up from her chair, lifts her T-shirt and loosens her belt. “Look,” she says, pointing to one of the belt’s holes. “When I got here I fixed my belt in this hole. Now I can fasten it in three holes before that one. That’s about 15cm less belt!”

At the time of our first interview Vermeulen had been on the Banting diet for 50 days. After the first 21 days at the clinic she was booked in for a further 30 days of addiction treatment because she had developed “secondary addictions”, such as spending excessive amounts of money on Banting-approved food.

Vermeulen is an attractive woman with long dark brown hair. But she’s unsettled. “Kate Moss said nothing tastes as good as skinny feels,” she contemplates, crossing her legs elegantly in her chair. “But for me, nothing felt as good as eating did. I was married to food.”

She was two years old when she first “stole” food – from the family dog’s bowl. “I climbed out of my feeding chair and ate the dog’s food after I had eaten my own,” she remembers. “That’s where it all started.”

Her schoolmates made up “all sorts” of names to insult Vermeulen about her weight. When she was 12, she remembers a boy punching her in the stomach, knocking her wind out, leaving her in a crumpled heap and chortling as he walked away: “Vet Let! [Fat girl]”

Textbook case: Laetitia Vermeulen* has battled binge eating disorder at great bodily, psychological and financial costs.

Textbook case: Laetitia Vermeulen* has battled binge eating disorder at great bodily, psychological and financial costs.

No escape

That year, her parents found jobs elsewhere in the country to escape the incessant bullying of their daughter in the small rural town where they were living. Not long afterwards, Vermeulen’s mother bought her daughter her first appetite suppressant.

It didn’t work.

At family lunches she’d eat the entire 1.5-litre tub of ice cream that was supposed to be served with the malva pudding before the dish was ready. On Father’s Days she would give her dad chocolates and “steal them back” the next day. When Vermeulen later worked at her parents’ guesthouse in the Cape Winelands town, where they’d moved, she would pilfer guests’ food. “You can’t stop. Your compulsion is stronger than your conscience,” she explains. “I’m someone who would like to have morals. But when it comes to my ‘addiction’, I’m falling through the cracks.”

Vermeulen would hoard food in her cottage on a wine farm where she lives. She would place chocolates everywhere throughout the house, within easy reach. She’d keep canned food until long after it had expired. “I was like a squirrel keeping it for the winter, but the winter would never arrive.”

A “carb-free” diet, according to Noakes, means one “ridiculously low in carbs”, as opposed to no carbs whatsoever.

“People need to restrict the carbs to a certain point so that they no longer get those cravings,” explains Rael Koping, the dietician who treated Vermeulen at Harmony Clinic. “Where it’s possible to remove substance abusers’ subject of addiction entirely from their lives, it’s different with food addiction, as people have to eat food to survive.”

And most foods contain carbs.

Low carb ‘cut-off’ level

Noakes refers to the point at which carbs need to be restricted as a “sub-addictive threshold”. In his bestselling book, The Real Meal Revolution, published in 2013, he recommends that carbs should be limited to between 25g and 50g a day. For perspective: according to Stellenbosch University dietician Celeste Naude a medium apple contains about 25g of carbs, a small, plain yoghurt 10g and half a cup of almonds 15g.

She elaborates: “If 25g of carbs is the ‘cut-off level’ in someone’s diet, it would mean that once an apple has for instance been consumed that person wouldn’t be allowed any more vegetables, fruits, nuts or dairy for the day, as they all contain carbs. The person would be left with pure meat and fat sources such as butter, oil or cheese to consume.”

Naude maintains traditional weight-loss diets, consisting of balanced amounts of healthy foods containing carbohydrates, proteins and fats, can include about 130g to 150g of carbohydrates a day depending on the total calories.

The Institute of Medicine, the health arm of the US’s National Academies, recommends at least 130g of daily carbs for a balanced eating plan that isn’t intended for weight loss. This is based on the average minimum amount of glucose used by the brain, and provides about 45% to 65% of the total calories of a 2 000-kilocalorie diet.

For weight loss, the total kilocalories are reduced, but the proportion provided by the carbs falls within the recommended range: for example, a 1 200-kilocalorie weight-loss diet with 45% carbs equals about 130g of carbs.

Noakes’s The Real Meal Revolution

Noakes’s The Real Meal Revolution

Fat as ‘fuel’

Vermeulen was put on a diet that included 50g of carbs a day; she was not allowed fruits because of their high sugar content. The scientific reasoning behind her low-carb diet was that she should deprive her body of carbohydrates to such an extent that it would go into a state of “ketosis”, when it would begin to use fat as energy or “fuel”.

Vermeulen had tried Noakes’s diet before but she couldn’t stick to it, but at Harmony Clinic she was in a controlled environment: it wasn’t possible to lay her hands on food after meals had been served, particularly not after 9pm, the time she usually started to binge.

Although there were restrictions on carbs and she wasn’t allowed any sugar, one “macronutrient” that had been discouraged in all her previous diets was allowed almost without restriction: saturated fat. She had to eat fatty meat, double cream Greek yoghurt, cream, butter and lots of cheese.

“Fat controls your hunger,” Vermeulen explains. “The fat makes you feel full for longer. After about a week my cravings for all those sugar-loaded chocolates and sweets, as well as high-carb processed foods like all the chips I used to eat, stopped. I no longer felt like binging.”

Fat is more “energy dense” than carbohydrates or proteins: one gram of fat provides nine kilocalories compared with four kilocalories in the case of carbohydrates and proteins – and fat empties slowly from the stomach during digestion, which is why it may sate some people for longer periods of time, says Naude.

Banting is called a low-carb-high-fat diet because it not only contains almost no carbs, but also a much higher percentage of total fat – which mainly consists of saturated fat such as animal fat and some plant-based oils such as coconut oil – than traditional, balanced diets.

Healthy fat controversy

It has made this way of eating enormously controversial because countless research studies have associated high intakes of animal fat (instead of unsaturated plant fats) with an increase in “bad” cholesterol levels, known as LDL cholesterol, and increased risk of “cardiovascular events” such as heart attacks and strokes.

Most Western countries, including South Africa, have based their dietary advice on such research and recommend that people replace “unhealthy, saturated fat” with “healthy, unsaturated fat” such as that in vegetable oils, nuts and fish oils. Noakes considers the vegetable oils included in balanced diets to be toxic.

According to Naude, there is convincing evidence that shows, “if you reduce your LDL cholesterol, then you can reduce your risk of heart disease. The studies consist of both observational and randomised controlled studies and the evidence is consistent across different study types.”

But Noakes disparages this evidence. “The theory that blood cholesterol and a high-fat diet are the causes of heart disease will be one of the greatest errors in the history of medicine,” he and Thomson proclaim in a summit press release.

Cholesterol and accusations of quackery

Thomson doesn’t have medical training. But she’s no stranger to heart problems; she’s the granddaughter of South Africa’s world-famous heart surgeon Chris Barnard, who performed the first human-to-human heart transplant on a patient with coronary artery disease.

Coronary artery disease, according to mainstream medical scientists, happens when the arteries that supply blood to heart muscle become hardened and narrowed because of cholesterol build-up.

Noakes’s views on cholesterol have resulted in cardiologists and academics publicly accusing him of being “criminal” and a “quack” who “flouts the Hippocratic Oath”. In one letter to the Cape Times, his views are equated with those of Aids quacks: “Having survived Aids denialism we do not need to be exposed to cholesterol denialism,” wrote one of his former colleagues.

In a Mail & Guardian article in 2012, Cape Town doctor Martinique Stilwell described Noakes as the “Malema of medicine”: a man with a horde of followers and considerable media sway, capable of producing charismatic, easy-to-hear and “probably irresponsible” solutions to very complex problems.

Noakes, however, is unmoved: “One of my colleagues has said I should be embraced as a world leader, like Chris Barnard. But exactly the opposite has happened.”

Diet “unsustainable”

Vermeulen’s Banting lifestyle was short-lived. After her release from Harmony in October she tried to follow the low-carb-high-fat diet but only managed to do so for a month. “I tried to bake my own Banting bread, but at R70 for a small packet of coconut or almond flower, I couldn’t afford it,” she said in January, three months after our first interview. “I found the diet unsustainable.”

In the three months that she was on the Banting diet, Vermeulen lost 10kg, but then, she says, “the fat stopped disappearing”.

“I tried Tim Noakes’s advice that if you’re not losing, you should go slow on the dairy. But it got really bad for me because all that was left to eat was meat, fat and a few types of vegetables.

“The more restricted my food choices became, the more I felt punished. It sends a message to you that you’re not worthy like other people of having an apple or a slice of whole-grain bread. You start feeling sorry for yourself and start craving and gorging the food you’re not allowed.”

Thomson acknowledges the Help’s dropout rate is “quite high”, at 40%. “Four out of 10 people fall off the wagon. It’s just really quite hard to stay on.”

Food restriction as a ‘trigger’

But psychiatrist Christopher Szabo says the reason why many binge eaters fail to “Bant” successfully is far more scientific: “It has been proven repeatedly that food restriction triggers binge-eating episodes. Therefore, when you start justifying restriction, it often accentuates the problem.”

Naude ascribes it to “willpower blowout”.

“Binge eaters can restrict and restrict and just can’t manage the restriction and basically rebound and have a binge-eating attack. The more restrictive a diet is, the less sustainable it is.

“Treating binge eating is about trying to normalise the person’s relationship with food again and introducing the component of tasting your food and enjoying different types of food. It’s about teaching moderation.”

According to Naude, “there is no high-quality evidence to show that sugar is addictive in the same way as substances like drugs or alcohol are addictive. Sugar is not classified as an addictive substance and the mechanisms involved in binge eating disorder are completely different.

“I’m also not aware of any research that has shown that there’s a medical or physiological mechanism in humans that regulates the specific level whereby suddenly you trigger some kind of sugar or carb addiction in your body.

Human research scant

Although several studies have found that sugar does stimulate the same pleasure centres in the brain as addictive drugs and alcohol, and often to a comparable extent, such research has been done on rats in controlled settings and not on people in everyday living environments.

According to a 2013 review of sugar addiction studies published in the journal Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, research that has been conducted on humans is incomplete.

“Solid evidence for the food-drug analogy is still scant and most of it is based on poorly validated inter-subjective comparisons and evaluations by people with drug addiction who are clearly not representative of the general population currently exposed to foods high in sugar,” the authors from the Institut des Maladies Neurodégénératives in Bordeax in France pointed out.

Says Naude: “While chocolates and sweets seem to be most common, people with binge eating disorder binge on anything they can lay their hands on – not only food with sugar and carbs.

The food they binge on, such as biscuits, sweets and chips, mostly also contain loads of fat and salt. To pin the solution for a complex problem on to sugar is shortsighted. Demonising any single nutrient in isolation is not helpful.”

Last year Naude and her colleagues at the Centre for Evidence-based Health Care at Stellenbosch University’s faculty of medicine and health sciences published a meta-analysis (a study that combines the results from similar studies) in the online medical journal PLOS ONE. It found that low-carb-high-fat diets result in no more weight loss than “recommended balanced diets” in the long term.

The study pooled the results of 19 clinical trials that monitored 3 209 overweight and obese participants for periods of between three months and two years. In each of the trials, the participants’ kilocalorie intake was controlled. In other words, those on low carbohydrate diets consumed the same amount of calories as those on “balanced diets”, says Naude.

“What the study really confirmed to us is that weight is not about the composition of low-carb-high-fat or high-carb-low-fat. It fundamentally boils down to the amount of energy you take in.”

Losing hunger

But Noakes has objected strongly to the Stellenbosch study, saying: “If you control the calories [when comparing the two types of diets] you falsely advantage low-fat diets, as people on low-fat diets with high amounts of carbohydrates are almost always hungry. The reason why people lose so much more weight on low carbohydrate-high fat diets is because they lose their hunger [because of the high fat intake] and that’s key.”

Naude, on the other hand, emphasises that, in the case of binge eating disorder, people mostly don’t eat because they’re hungry.

“The eating disorder is often a manifestation of a deep underlying psychological issue that is related to their behaviour. A high-fat diet can therefore not be seen as a foolproof method that everybody who has got binge eating disorder will respond to, although it might work for some.

“In the same way, some might respond to more vegetables and fruit and other changes in eating patterns. You can’t make a direct causal link between a high-fat intake and reduced food intake. It’s very individual. The key here is that different diets work for different people.”

Loneliness was key

Vermeulen hasn’t binged since leaving the clinic. But she says it wasn’t a diet that “saved” her. “The psychological counselling there helped to make me realise why I used food to ease my loneliness, but the Banting diet didn’t help. I felt that the label of sugar and carb addict was stuck on my forehead like a sticker. It made me feel stigmatised.”

She has stopped watching TV because she says she realised it was a major part of her binge-eating problem.

“Food and television and DVDs was a package for me. Taking out movies or watching hours of TV might trigger a binge-eating attack in my case,” she reasons.

Vermeulen continues to receive therapy from a clinical psychologist and also sees a psychiatrist. “I’m on depression medication and still get anxious regularly [depression and anxiousness are commonly associated with binge eating disorder], particularly at work, but I’m more productive and structured.”

She’s also seeing a biokineticist twice a week, who has created an exercise plan for her. “I’ve picked up some of the weight I lost at the clinic but it’s OK. I’ll lose it again.”

Two weeks after she was released from Harmony Clinic, Vermeulen took a leap of faith and went on a blind date with a 43-year-old farmer. She says they “clicked” immediately.

She smiles: “I no longer feel lonely and he’s helping me to accept my-self. Last night he told me: ‘Do you know how beautiful your voluptuous body is?’ ”

* Laetitia Vermeulen is a pseudonym

• Dietician Rael Koping and Tim Noakes are no longer involved in the Help eating programme. This is the first in a two-part series on Banting and binge eating disorder. Next week will focus on the science or lack thereof around “sugar and carb addiction”. We will tell the stories of Tania Bosman and Kerry Hammerton, for whom the Banting diet has worked. It will be published on the health pages

• See “I was a Tim Noakes guinea pig”

[This article was originally published on 13 February 2013]