Marten du Preez

Used as a gateway to the world’s southernmost continent since the 18th century, South Africa has been actively involved in scientific research in Antarctica and in its only overseas territory, the Prince Edward Islands, since the end of World War II.

The Antarctica Legacy of South Africa, a programme based at Stellenbosch University and funded by the National Research Foundation, hopes “to collect and store the stories, memories, photographs and other documents pertaining to South Africans in the Antarctic and on the Prince Edward Islands” to serve both as the basis for future research and to applaud scientists and citizens studying some of the most remote terrains in the world, Sarah Wild writes.

Although Cape Town was the starting point of other countries’ Antarctic expeditions, the first South African expedition to the continent was launched only in the summer of 1959-1960. All 10 members of this expedition were part of the South African Weather Bureau. Today, the department of environmental affairs funds and is responsible for maintaining South Africa’s activities on Antarctica and the surrounding islands.

The Norwegian ship Polarbjorn (below) transported the first SANAE team to Antarctica. Dick Bonnema (above) was one of the team. They spent much of their time on board playing games, making music and reading.

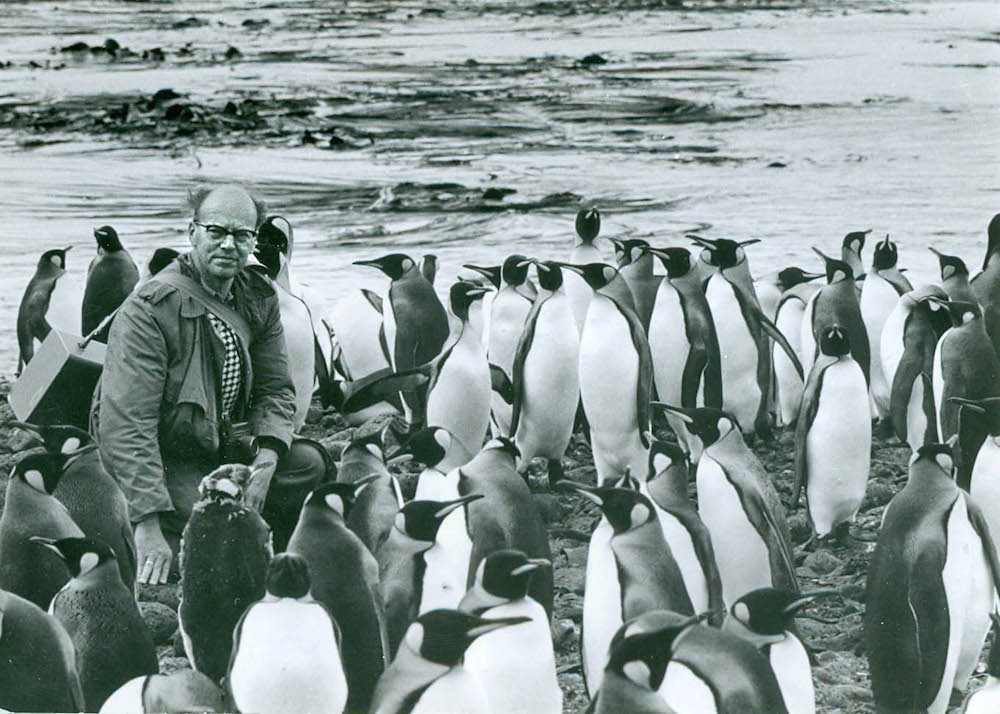

Eduard van Zinderen Bakker Snr is recognised for initiating biological research programmes on Marion Island in the 1960s. The Prince Edward Islands, which comprise Marion Island and Prince Edward Island, are South Africa’s only overseas territory. They were officially annexed in 1948. The occupation of the islands was called ‘Operation Snoektown’.

Christo Wolfaardt wrestles a seal pup on Marion Island in April 1961, while a male Rhodesian Ridgeback puppy sniffs at it. The dog, called Oubaas, stayed on the island until March 1965, and has a hill named after him.

Newspaper clippings, letters, photographs, telegrams and other forms of communication are being collected by the Antarctica Legacy of South Africa project, in an attempt to preserve the history of the country’s involvement on the continent and its surrounding islands.

Antarctica, with its pristine skies and the presence of the South Pole, is ideal for space science. The South African National Space Agency’s head of space science, Lee-Anne McKinnell, says: “The reason we do science in Antarctica is because it’s the most amazing place to get info on the space environment … If there is a [solar] storm coming, we’ll see it at SANAE first. The base is vital in terms of South African science.” One of the main instruments used to study space weather is the SuperDARN high-frequency digital radar, which is part of a network of more than 30 radars involving scientists and funding agencies in 16 countries. (Rob Coetzee)

Marion15 team members tan on Boulders Beach on Marion Island. Expeditions are named after the island and then the number of the expedition. According to the department of environmental affairs, which runs South Africa’s Antarctic programme, the island is usually manned by a senior meteorologist, two assistants, a medical orderly, a radio technician, a diesel mechanic, field assistants and biologists.

A member of SANAE3 washes his face in 1962.

Llewellyn Kriedemann and another team member travel on an alpine cargo ski in 2007. In the early days of South Africa’s involvement on Antarctica, huskies pulled team members on field expeditions. And, as if to make the point that it is never too cold for South Africans to indulge in a favourite pastime, team members have a braai in 1969 (below).

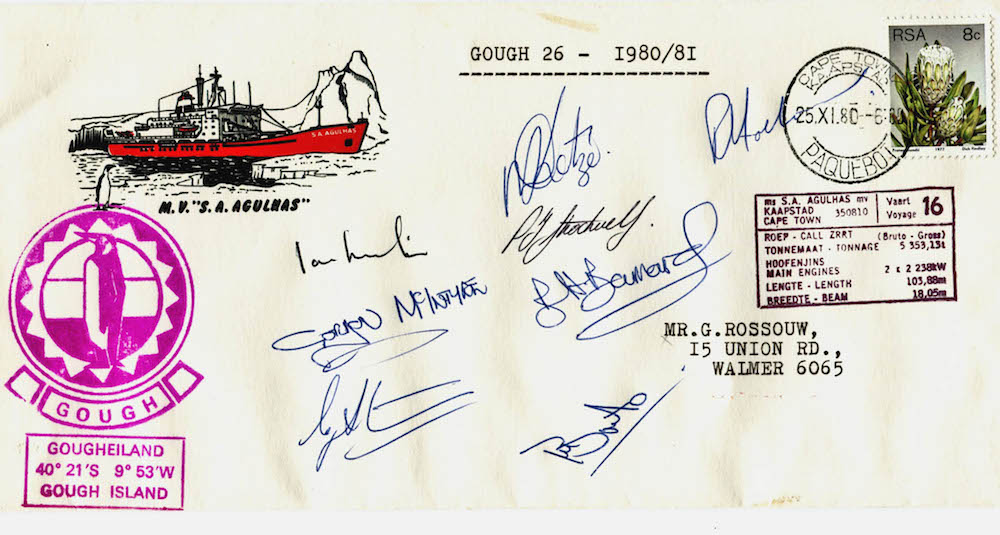

Team members collect stamps on envelopes of their trips into the Southern Ocean. This envelope (below) was collected by a team member of Gough26 in 1980. South Africa has maintained a weather station on Gough Island since 1956.

The historical information on this page relies heavily on an article published in the South African Journal of Antarctic Research in 1991, titled A history of South African involvement in Antarctica and at the Prince Edward Islands. One of its authors, John Cooper, is the principal investigator of the legacy project.