Freedom Park has a Zen-like tranquility

At the foot of the many stairs leading up to the Voortrekker Monument stands a small, old-fashioned postbox. Barely noticeable, coloured red and numbered Tshwane 160, it gets emptied several times a week but there is no longer a monument post stamp, and therefore no opportunity to send a letter or postcard franked with the words “Voortrekker Monument” in black ink.

Strange as it sounds, such envelopes and stamps were once greatly sought after. They signalled the idea that the monument radiated its unambiguous force into the world. It was not only a political statement but a site of pilgrimage, a site to see and be seen in, and while some of its ideological fires have been dampened in the democratic age, it is still a place that easily raises the political hackles.

A granite structure built to endure whatever foul moods the weather and history might bring, the Voortrekker Monument has not changed in any tangible way since the on-site post office first franked the mail in 1949. The world around it has changed, though, often profoundly. Forty-three percent of all Chinese tourists who visit South Africa, for instance, visit the monument, a figure that runs into tens of thousands.

They take photographs and coo admiringly as they ascend the staircases up into the dome to sample the monument’s pitch-perfect acoustics. They photograph the jasmine and admire the old ox wagon at the base of the stairs, and the commanding views, soaking up the brutal splendour of it all. Never before in its long and baleful history have so many panoramas of Pretoria’s skyline been stored on cellphones or taken home to China, either to gather dust or illustrate a story of victory against overwhelming odds.

“We cater for their needs,” says Geraldine Paulsen, the monument’s press officer, when asked what it is about the place that exerts such fascination for Chinese visitors. She adds that pamphlets and posters are written in Mandarin and that Sonja Lombard, the monument’s managing director, has travelled to China to advertise the monument’s attractions and drum up business.

Chinese tourist attraction

Despite Tshwane’s many attractions, Paulsen believes that, in the city, the Chinese visit only the monument. That is before either heading east to the Kruger National Park or west, to Sun City. Although the Union Buildings fan out majestically in the middle distance, she says they find that the Chinese have no desire to visit them, or, for that matter, the shopping precinct of Brooklyn or the blue fortress that is Loftus Versfeld. They photograph Anton van Wouw’s statue of an Afrikaner woman and her children at the monument’s base and pay hushed respects at the cenotaph, before invariably moving on.

Gazing roughly northeast from the pedestrian walkway at the top of the monument, you can see the spires of Freedom Park almost within whispering distance. There is a natural link between the two places of remembrance and there is indeed a road between the Voortrekker Monument and Freedom Park, making what is logical access between the two perfectly easy.

There is something sulky and obdurate about the Voortrekker Monument, a granite monument expressive of a granite mentality. (Photos: Madelene Cronjé, M&G)

Inaugurated by President Jacob Zuma on Reconciliation Day in 2011, it was called “Reconciliation Road” which, we were told at the time, “indicates progress in the national project of reconciliation”. As is the case with reconciliation in all its forms, it was intended to remain open, an enduring bridge of promise between two mutually uncomprehending spaces.

If you look down into the valley which separates the Voortrekker Monument and Salvokop, the koppie upon which Freedom Park rests today, however, you are greeted with a sight more reminiscent of a Cold War border post. There is a gate, a boom and what looks like a sentry box. In this time of anger about shared monuments and heritage, where the defacing of monuments is seen as politically heroic, there is no traffic, Chinese or otherwise, between the two monuments along Reconciliation Road.

Answers to the question of why the closure was deemed necessary are inconclusive, with each side accusing the other of reneging on the memorandum of understanding that came into existence when the president took his step in the “project of nation-building” less than three-and-a-half years ago.

Spiritually removed

It is still possible, of course, to pay one’s respects at both sites, as I did earlier in the week, but the two have been spiritually removed from each other by the road’s closure. You are obliged now to take the longer way round, via Skietpoort Road, making a detour that serves to separate the two memorials even further, both physically and emotionally.

It is a strange state of affairs, given that the two are so completely different anyway and in no particular need of being separated still further. There is something sulky and obdurate about the Voortrekker Monument – whichever way you dress it up, it is a granite monument expressive of a granite mentality.

Reconciliation Road, which linked Freedom Park and the Voortrekker Monument, has been closed inexplicably for months.

By contrast, Freedom Park is a far gentler space, full of pathways through the sugarbush trees and tucked-away spaces that encourage calm and reflection. The use of water, with its soothing and healing properties, further reinforces the Zen garden feel of the place, a delicate, slightly trippy space of olive trees, ordered pathways and empty, manicured lawns.

While reconciliation between the two spaces seems a long way off, it was noticeable during my visit – a slow Monday, for the record – how much more life there was at the Voortrekker Monument. Freedom Park’s security guards, ticket sellers and gardeners were unfailingly polite and keen to help but there were no visitors at the facility, just the occasional crackle of security’s walkie-talkies and the distant hum of Pretoria’s many highways that encircle the memorial.

Melancholy air

The restaurant couldn’t be visited because it housed only one thing –the brightly-coloured Tupperware boxes that contained workers’ lunches – and there were telltale signs of subtle ageing and wear and tear. The casing of ground-level light fittings on the pathways to the Wall of Remembrance often spilled out onto the path itself and although the facility is pristine, melancholy hung in the air. This is the peculiarly accented melancholy of underuse, of so much time and effort spent in the creation of a special place which no one seems to see or care for.

In 1999, Nelson Mandela referred to the need for a “people’s shrine” to commemorate and honour those who gave their lives so others could enjoy the fruits of democracy. It would be a sad day indeed if that shrine became a white elephant through underuse and lack of drive to capture the markets that would make Freedom Park a far more vibrant and engaged-with space.

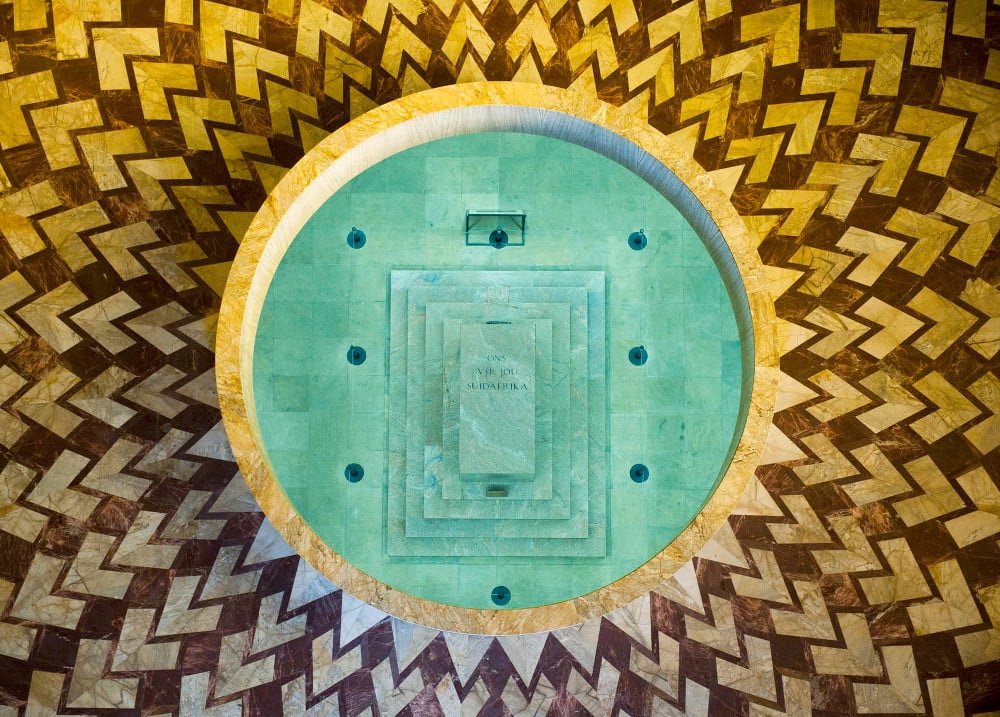

The cenotaph on the floor of the Voortrekker Monument seen from the domed ceiling – a view well known to Chinese tourists.

More significantly, perhaps, in the closure of Reconciliation Road there is something of the heavy-handedness which led to the building – mainly from public subscription – of the Voortrekker Monument.

Like so much in contemporary South African life, from the vandalism of statues, to the utterances of King Goodwill Zwelethini, to the stabbing of a man because he speaks another language, we are walking steadfastly away from tolerance and reconciliation.

It is a path which leads to only horror and dread.

Division and difference does not end at the ideological

Although they commemorate very different periods in South African history, superficially Freedom Park and the Voortrekker Monument are exactly the same: monuments designed to commemorate the heroic and the fallen.

The resemblance, however, ends there, for while Freedom Park has an operating budget of R64-million and falls under the department of arts and culture as a national monument, the Voortrekker Monument has an entirely different commercial and legal status.

First, the Voortrekker Monument is a section 21 company – a company not for gain, in other words – and second it isn’t a national monument and thus doesn’t qualify for any government spending. According to Geraldine Paulsen, the monument’s press officer, it is a grade-one national heritage site and has annual “running costs” in the region of R16-million. It employs 84 people on its exceptionally large 553 hectare site, including administrators and gardeners. “The majority of that land – some small parcels aren’t ours – belongs to the monument,” says Paulsen.

Given its commercial status, the monument has to raise its own funds. Paulsen says that 250 000 visitors pass through the monument in a year, although not all of these are paying customers.

Other than gate fees, the monument holds a number of military fairs displaying hardware and equipment through the year, with one such fair coming up early next month. Paulsen says that such fairs rate as some of her personal favourites for the year.

“We have an old 1830s cannon called ‘Susanna’,” she grins. “She was dug up underneath the grounds of Cape Town High School in 2007 and was donated to us. We cleaned her off – she’s still able to fire. That will be one of the highlights at this year’s fair.”

Freedom Park employs 97 staff members (including gardeners, security and administrative staff) and receives approximately 4 500 guests a month, roughly 54 000 a year.

“We are now putting a lot of effort into marketing and to attracting more visitors,” Freedom Park’s acting chief executive, Jane Mufamadi, tells me, adding that the monument only became “fully operational” two years ago, a strange state of affairs given that several sections of the park were opened as far back as 2009.

When asked why the Chinese visitors up the road at the Voortrekker Monument don’t visit Freedom Park, she replied: “We established a very good network with the Chinese market but also advised them to wait until we are fully ready for … their market.”

Despite this, Freedom Park is a serene and even graceful space, well worth the visit and easily accessible from the N1 highway.

It seems to suffer from a severe over-employment problem, however, with too many security guards, gardeners and ticket officers and too few visitors and paying guests.

The closure of “Reconciliation Road” between Freedom Park and the Voortrekker Monument in these fraught and fractious times is a significant blot on the ability of both monuments to co-operate in the spirit of nation-building.