Some of the artists who will be going as part of the Johannesburg pavilion show: Arya Lalloo

A day after the attacks that tore through Durban’s city centre began and displaced thousands of foreigners, I meet Christopher Till, the director of the Apartheid Museum, and Jeremy Rose, from the Mashabane Rose architecture firm, to discuss their being awarded the right to curate the South African pavilion at the 56th la Biennale di Venezia. It is difficult not to launch into issues relating to the headlines.

READ Kenyan artists’ outcry wakes up the government

“So many things are happening in our country, and we have been looking for artists who are concerned with, and articulating those issues,” Till says, explaining how they chose the 13 artists to participate in the exhibition, titled What Remains is Tomorrow.

Referring to artists’ reactions to the ongoing xenophobic attacks, Rose talks about the work of visual artist Gerald Machona, whose art has reflected on this topic. “That is why we have selected him.”

The Zimbabwean-born, Cape Town-based artist will show alongside acclaimed artists such as Willem Boshoff and Robin Rhode in the 250m2 exhibition space.

Rose, who has worked on public art projects such as the Freedom Park Museum and the Hector Pieterson Memorial, says, although the selection of artists and the title of the exhibition is related to history, the voices of the artists are contemporary.

“We’re also working with artist Haroon Gunn-Salie towards a project on the sculptures being defaced,” Rose says.

Till adds: “[Composer] Warrick Sony, who works with sound, has used footage from Marikana and the soundtrack on his film pieces. These artworks are contemporary; they echo elements of the past but they are now.”

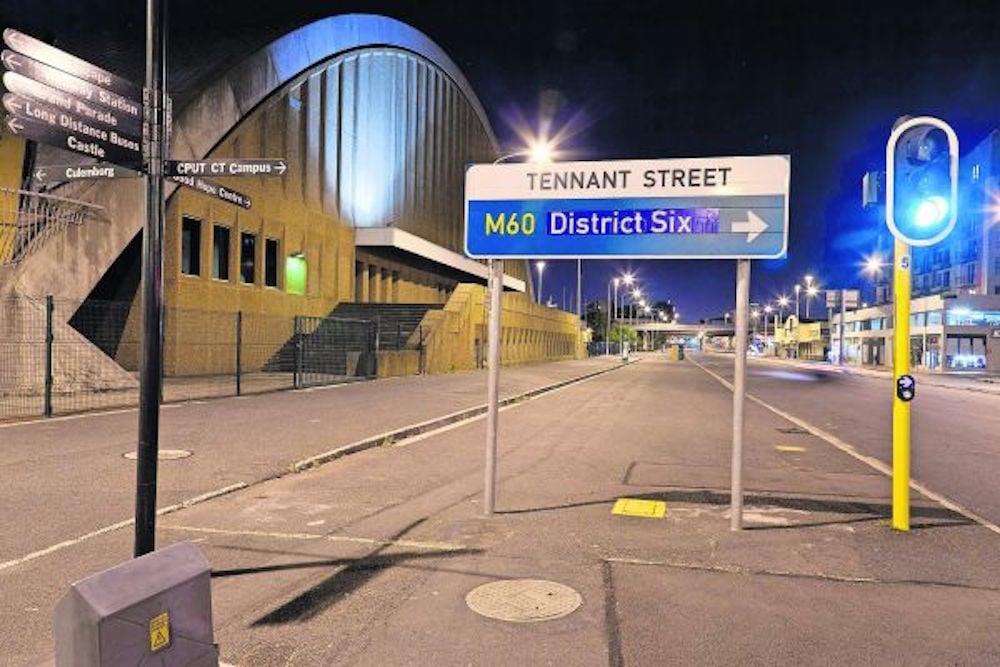

Artist Haroon Gunn-Salie’s District Six signage.

Mired in controversy

Rose and Till are surprisingly calm for two people who were given the official green light by the arts and culture department only a month before the exhibition, although the department had finalised contracts weeks before.

Tills says: “Originally, we put in our proposal in October last year”, but they knew the deal was theirs two months before the exhibition. They say they are prepared and the groundwork has been done.

But, judging from the last-minute press releases issued by the government and with the PR company Fourthwall Books being roped in, it’s apparent that the chaos sweeping through the country has not skipped the South African pavilion.

Given that the past two pavilions were mired in controversy – funding deals and an unrepresentative artist line-up – this is nothing new.

Johannesburg pavilion

In another part of the city in the same week, some of the 18 artists who are attending the biennale as part of the Johannesburg pavilion are gathered at a glass house in Westcliff. The Jo’burg pavilion is being run by the nonprofit organisation 133 Arts Foundation, owned by Roelof Petrus van Wyk, and the FNB Jo’burg Art Fair. It is also being supported by the City of Johannesburg and private funders.

But it’s not as easy as it looks, says the barefooted Van Wyk, owner of the expansive ultramodern home and the organiser of this pavilion. From arranging visas to handling the press, Van Wyk is dealing with the logistical nightmares.

“It just goes to show how much can be done with nothing,” he adds.

Unlike the roughly R10-million price tag for the South African pavilion, Van Wyk says his budget is a fraction of that amount. “We are taking 18 artists physically there, plus four support people. So that’s 22 people to accommodate, fly and feed, etcetera, for three-quarters of a million rand, when the South African pavilion’s rental alone is R1.5-million.”

Van Wyk says they chose contemporary African film and live performance artists because “it is an easy way to get art shown in Venice. We don’t have to pack or crate anything, and we don’t have to pay insurance [for visual art]. The insurance is the same amount that we’re using to get everyone there.”

‘Jo’burg pavilion is guerrilla in a way‘

So, although the South African pavilion will be hosted in the grand Sale d’Armi in the Arsenale, the performance artists and filmmakers of the Jo’burg pavilion will take to the streets, alleyways and cafés of Venice.

“The Jo’burg pavilion is guerrilla in a way, but it is also welcomed. It’s an interesting tension to think about,” the multidisciplinary artist Bettina Malcomess says. She has been preparing a performance piece she will finalise in the Italian city.

“The fringe in Venice is quite an established thing; it’s a productive space that people do recognise. This space speaks to the official biennale,” she says.

Those making their way to Venice are young and diverse and include performance artists such as the Standard Bank Young Artist award-winners Athi-Patra Ruga, Donna Kukuma and Anthea Moys, video artist Bogosi Sekhukhuni and filmmaker Sibs Shongwe-La Mer.

Asked about the thinking behind the wide array of artists and a titleless exhibition, Van Wyk says: “We don’t want this to be a curated show with 24 pictures on a wall and they all have some relationship. The artists themselves actually forge those relationships between them.”

Malcomess, who is also a curator and writer, says: “Even though it’s called the Jo’burg pavilion, it’s definitely not about Jo’burg. We don’t want to be curiosities or performing Jo’burg.”

She and the filmmaker Arya Lalloo, who is seated beside her, say it is just the framework to the pavilion.

Lack of representation

Despite not having an official theme, Van Wyk says the pavilion is in memory of the final Johannesburg Biennale in 1997, which was curated by Okwui Enwezor, the Venice Biennale’s first African curator.

“It’s kind of a nod to Okwui and, in a way, thanking him because that Jo’burg Biennale in 1997 is a world landmark event in the art world and the world of biennales.”

This year, the Venice biennale is themed All the World’s Futures, which is explained by Enwezor. “How can the current disquiet of our time be properly grasped, made comprehensible, examined and articulated? Over the course of the last two centuries, the radical changes have made new and fascinating ideas subject matter for artists, writers, filmmakers, performers, composers, musicians. It is with this recognition that the 56th International Exhibition of la Biennale di Venezia proposes All the World’s Futures, a project devoted to a fresh appraisal of the relationship of art and artists to the current state of things.”

So, as the world readies for the biennale and its main exhibition, which is curated by a black man, looking at both South African pavilions, particularly the one funded by the department, may raise the question: In a country whose government is apparently so concerned about transformation, why is there a lack of representation of black artists and curators on this world stage?

Future of the SA pavilion

“This is surely a joke? Two middle-aged white men, one an architect and the other a civil servant and arts administrator, are the curators of our pavilion?” someone comments on the Mail & Guardian report about the artists going to Venice as part of the South African pavilion.

The 13 artists includes only three women (Jo Ractliffe, Diane Victor and Nandipha Mntambo) and only one black woman (Mntambo). I ask Rose and Till about having a list of artists that is representative of the country’s demographics.

“There is obviously pressure to have black artists at the South African pavilion,” says Rose. “But we wanted [the artworks at the show] to be issues based. We wanted to raise issues and deal with representivity as best we can.

“We approached the selection [of artists] based on [how they] present issues [in their artwork]. When you go through the list, what is interesting is the issues they represent in their work. That is far more important.”

If your outlook is that of an established white male, overlooking the perspective of black female artists such as the award-winning photographer Zanele Muholi or performance artist Nelisiwe Xaba might not be that hard.

But, Till says, during the six-month period of the biennale, “we will look at the viability of bringing new artwork on to the show”.

With the biennale opening on May?9, many might wonder about the future of the South African pavilion, which now, as in the past, has had to deliver at the last moment, and has been often linked to controversy. Can a country whose reputation of butchering foreigners is being streamed around the world afford the further embarrassment of a pavilion in crisis?