Out of hand: Tammy-Ann Julies* says she drank until she was seven months pregnant with her son

Tammy-Ann Julies* remembers “feeding” her eldest son alcohol for the first time about two years ago. It was a late Friday afternoon and the then eight-year-old Owen* and his mother shared a 750ml bottle of Black Label beer.

They were sitting in the houthok [wooden shack] that Julies (30) and her husband (36) had built in the back yard of one of the pink and brown municipal flats in Roodewal, a mainly coloured township in the Cape Winelands.

Julies’s husband wasn’t home from work yet.

Inside the houthok, things were getting “really jolly” and “loud” as Julies and her son moved on to whisky: neat, on ice. Julies’s usually neat black hair, cut in a bob, was soon tousled.

“He got drunk, just like I got drunk,” Julies recalls her son’s reaction to the alcohol. “We both eventually tieped [passed out].” But right then, they were “in the moment”. “Chirpy and perky, you know,” Julies remembers.

After the mother and son had each had a “few sips” of whisky, Julies lit two cigarettes. One for her, one for Owen.

Then Julies’s five-year-old daughter, Alicia*, woke up. She had been asleep on her parents’ double bed. Julies fetched Alicia’s favourite plastic cup and poured a whisky for her daughter. Shortly thereafter, her husband arrived and “joined the party”.

Julies pauses for a moment. Then the friendly woman with the open face reaches for her cellphone on the tiny, wobbly table next to her and scrolls to a photo of her children. She looks up, slowly. “When we drank together we were just that happy family,” Julies says.

She clutches her phone tightly. “We were just lekker when we had alcohol in our bodies. We understood each other 100% because mommy and daddy and the kiddies were all drinking out of the same bottle.”

Houthok homes

In her houthok, Julies sits on an old couch, her shiny purple top and bright pink pyjama pants contrasting gaudily with the tattered maroon and green upholstery. She’s next to a broken window held together with the packaging of menstrual pads and pieces of yellow masking tape. It’s about 9am on a fresh autumn morning and she’s breastfeeding her 10-month-old son, Jason*. Loud music filters in from surrounding flats.

There are hoks in the back yards of most of the ground-level apartments. For each letter of the alphabet there are two three-storey blocks of about 28 flats. Up to 20 people live in some of the two-bedroom flats. The walls are layered with graffiti; dripping washing hangs over staircase rails or on makeshift washing lines between buildings. Linen, t-shirts and underwear dry in a slight breeze.

Inside Julies’s hok Jason clutches his mother’s breast with both hands, gulping from it eagerly. A seven-year-old girl skips into the room. It’s Alicia. “Mammie, where’s my ball?” she asks. It’s a public holiday; she’s not in school today.

Julies rises slowly, her son still on her breast, hands her daughter an old, cracked rugby ball and says: “Mammie’s just talking to the tannie. Go play outside so long, okay?” The little girl nods and disappears with her ball through the door to play on one of the sprawling, dusty vlakkies between the buildings. There are no trees or playgrounds here.

“Things went horribly wrong”

Julies begins talking again, another memory bubbling to the surface. One day, about 18 months ago, when Julies was pregnant with Jason, “things went horribly wrong” when the Julies family visited relatives in Paarl for a drinking party.

The mother recalls “shoving a whole glass of whisky” down Alicia’s throat.

“My husband didn’t like that. He started to hit me,” she says. “But I wasn’t bothered and I continued giving her the whisky. I felt: ‘I’m drinking, he’s drinking; everyone’s drinking. I’m going to force the child to drink too.'”

Soon afterwards, says Julies, Alicia’s eyes began “spinning”.

“She looked like she was going to have a fit. But I was too drunk to take it seriously,” Julies says. “When you’re in the clutches of alcohol you don’t care what you do at such a moment.”

At the time, Julies and her husband differed from most people in Roodewal: they had what were considered good jobs in the district. Julies earned R5 000 a month as a packer at a local chicken factory and her spouse was a machine operator at an engineering firm, earning a monthly salary of R12 000.

They were paying R400 rent for their back-yard hok and received social grants for their children. “There was lots of money for dop [alcohol],” says Julies.

Weekend binges

Like most of their friends, the Julieses binged over weekends but didn’t drink in the week.

“On Friday evenings we’d buy two bottles of Red Heart Rum and a crate of beer [a dozen 750ml quart bottles]. On Sundays we’d buy new supplies, even on Saturdays when needed. But Sundays were our best and biggest drinking days. Then we didn’t worry about how much we spent.”

Julies pats her baby son affectionately on his rump.

“I think I was very lucky on that day when my daughter’s eyes rolled over,” she says. “My aunt gave her milk, which made her vomit out all the whisky. After a few hours she seemed fine.”

But, unbeknown to them, the consequences of all the heavy drinking were steadily catching up with the family. Shortly after the incident in Paarl, the Julies couple both lost their jobs. “On Mondays we were constantly absent from work because we were still drunk, so eventually we got fired,” Julies says. “Then all we had left to survive on was the children’s AllPay [social grants]. But we even drank that out.”

I’m “worried about my children”

The plastic that fills the hole in the hok’s broken window flaps in the breeze. Julies places Jason, who has fallen asleep on her breast, on her bed. She covers him with a blanket and says: “I’m very worried about my children.”

Julies’s concern is far from misplaced. A United States study published in the Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs this year found that children who had drunk alcohol by the age of 11 were five times more likely to drink by the time they were in their mid-teens and were four times more prone to binge drinking than those who had not tasted alcohol at an early age.

Teenagers who drink alcohol are common in Roodewal. Many drop out of school by the age of 14 or 15. But Julies is troubled by more than her children’s vulnerability to becoming drinking adolescents. “I drank right throughout the pregnancies of my eldest son and daughter and only stopped when I was seven months pregnant with the baby,” she admits. “They could be brain damaged.”

Alcohol and pregnancy

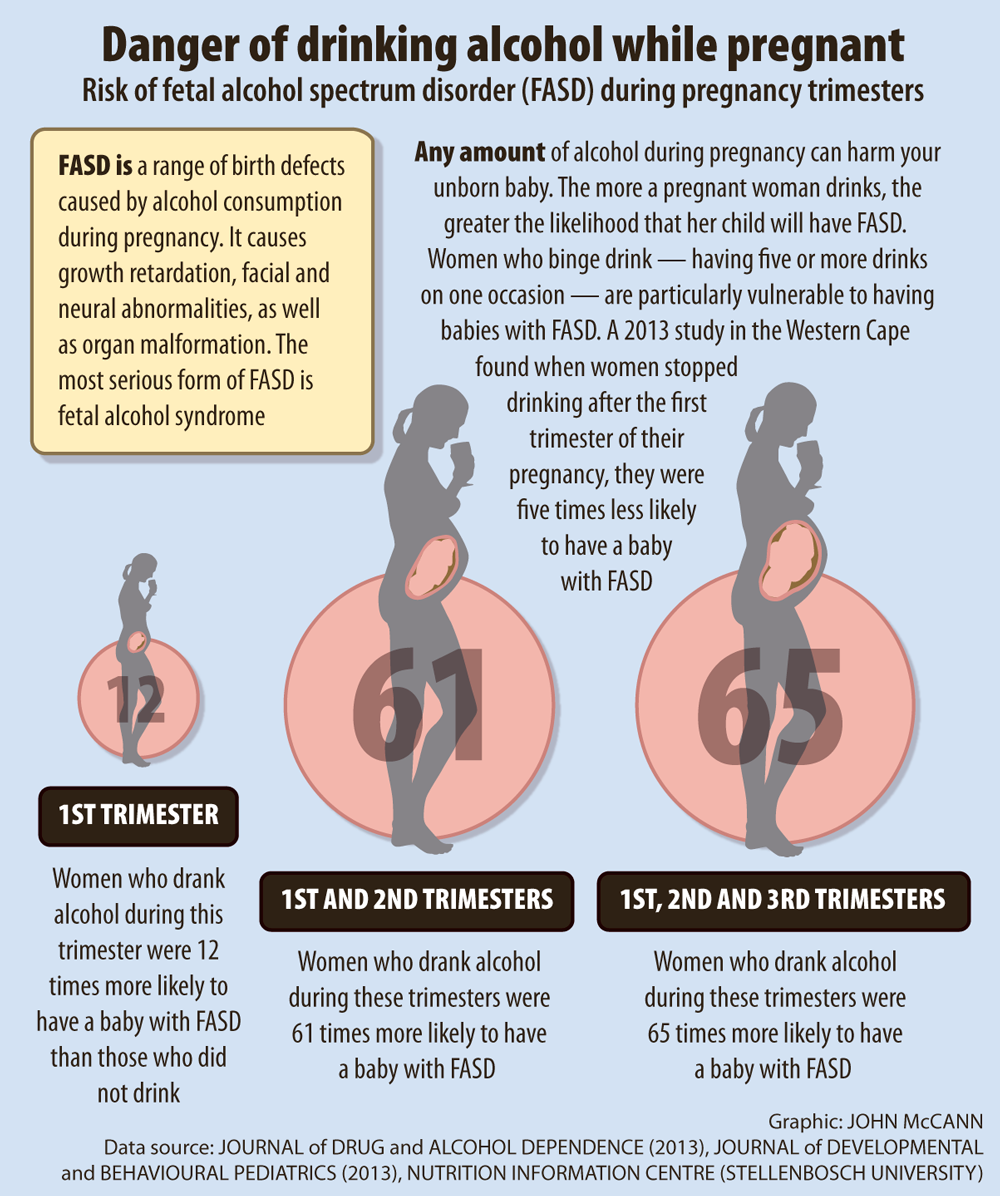

One weekend afternoon, when Julies was about six months pregnant with Jason “and well into quite a few beers”, a local woman knocked on her door. She was a lay counsellor or mentor from FASfacts, an organisation that works to eradicate fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), which is caused by drinking alcohol during pregnancy.

That’s when Julies learned that Jason and Alicia had their first taste of alcohol long before they were eight and four, respectively. “It was when they were in my tummy,” she says quietly. “I had no idea how my babies grew in my stomach and how they could get harmed, until I saw those video clips and flip charts.”

Julies fiddles anxiously with her hands, folds them and sighs: “When a pregnant mommy drinks, so does the baby in her womb.”

Studies have shown that when a pregnant woman consumes alcohol, the substance is able to cross the placental membrane, which separates maternal blood from fetal blood, within 20 minutes. The alcohol, which is toxic to the baby, is then transported directly to all the developing tissues of the fetus and can hinder the division of cells in the brain and stop them from migrating to their correct positions.

Soraya Seedat of Stellenbosch University’s psychiatry department says unborn babies have “few physiological resources” to break down alcohol, because their livers are not fully developed. Binge drinking is particularly dangerous to a fetus because it makes the mother’s blood alcohol levels peak, bombarding the fetus with alcohol.

Lasting effects

The Foundation for Alcohol Related Research in Cape Town defines binge drinking as five or more drinks – a 340ml beer or 175ml glass of wine are considered standard drinks – in one sitting of two to three hours.

Says Seedat: “When a mother binges very heavily, the greater concentration of alcohol passing to the fetus will take longer to be broken down by the fetus. And it is possible that the alcohol remains active longer within the fetus and has greater effects on brain function, contributing to long-lasting effects associated with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder.”

Some studies have shown that even one binge-drinking session could harm a fetus – it all depends on how the mother’s body metabolises the alcohol.

The worst form of FASD is fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS). The average IQ of a child with FAS is between 65 and 75, the norm being 100. Most FAS children are also “growth-retarded”, with some having wide-set eyes, low nasal bridges and thin upper lips without a vertical groove between the nose and upper lip, according to the foundation.

Such children, including those with partial FAS or other “less severe” forms of FASD, can also suffer damaged organs and a range of neuro-behavioural problems such as hyperactivity and attention deficit disorder.

Two of Julies’s children were born underweight, a typical FASD characteristic. Owen weighed 2.4kg and Jason only 1.2kg. “We were in the hospital for weeks after his birth,” Julies says. “He was really very small.”

Intellectual impairment

Owen, who is 10 and in grade three, is “very slow at school” and struggles to read, says his mother. His teachers have called Julies to the school on several occasions. “Every time they tell me they’re not sure whether he’s going to pass his grade, or even that term,” she sighs. “The only thing I can do is to pray.”

Owen hasn’t been officially diagnosed with FASD, but Julies fears that it will happen soon.

According to a 2008 FASD report by the Medical Research Council, the universities of Cape Town and Pretoria, and the United Nations Children’s Fund, “prenatal alcohol exposure” is the “leading cause of intellectual impairment in the world”. It is 30 to 50 times more common than Down’s syndrome.

Although FASD studies have not been conducted in Roodewal, 2013 research published in the Alcohol Clinical and Experimental Research journal revealed that between 13.6% and 20.9% of grade one children in four nearby towns, with similar socioeconomic profiles to Roodewal, were affected by FASD – the highest reported figure in the world.

Another study found that binge drinking over weekends was “normative” for up to 40% of women in this population, whereas drinking moderately and during the week is rare.

Julies whispers: “I decided to stop drinking when I realised what I was doing to my baby. It took me about a month to let go completely of the alcohol. But I’m afraid it was already too late.”

Drinking culture

Geraldine Mostert* blows a huge, shocking-pink chewing gum bubble from her lips. It snaps as she passes nine quarts of beer to a man in his 20s. It’s just after 10am. Outside the unlicensed shebeen, unemployed young men are sitting around as toddlers meander among them.

Mostert is 17. She dropped out of school when she was 15 and now runs her father’s shebeen from the family flat in the building where the Julies’s hok is situated.

It’s not only the shebeen that’s illegal. Like many drinkers here, Mostert herself is below the legal drinking age of 18.

The teenager, wearing a bright purple windbreaker and neon-yellow Puma takkies bought with the money she earns at the shebeen, says she sells about 20 crates of quarts a day – that’s 240 750ml beers. She charges R11 a beer, a third of the price that an average suburban bar would ask.

“Men in their 20s are my biggest clients, but I also sell to women,” Mostert says. “Just last week a pregnant woman came in to buy five quarts, but she said it was for other people.”

Inside the flat, brown South African Breweries beer crates are stacked against three of the four walls, along with a huge sound system that is soon blasting R&B at full volume. On the fourth wall is a framed picture of embroidered hands in prayer, with the words Loof die Here (Praise the Lord) sewn in red and blue at the bottom. Mostert smiles and says: “It’s my ouma who made it.”

She adds that she and her friends, mostly minors, share about six quarts among themselves every day. “Every day I drink two by myself,” she deadpans.

A boy, who says he’s 11, arrives at the shebeen clutching a R50 note to buy “four beers for my father”. While serving the youngster, Mostert says: “I don’t really know what happens to a baby when a pregnant woman drinks. But I think the babies come out funny.”

Handing the boy R6 in change, she adds: “I’ve seen five such kids here around the shebeen. They’re short and look a bit retarded.”

A baby wails inside the flat, adding to the cacophony. “It’s my brother’s child,” says Mostert, continuing: “I think the women drink because they’ve got problems at home. Their husbands hit them and their lives are full of stress.”

Street legal: One of the few licensed liquor stores in Roodewal; most are illegal shebeens.

Street legal: One of the few licensed liquor stores in Roodewal; most are illegal shebeens.

Link with poverty

Whereas numerous South African studies have found a link between poverty and FASD, relatively high rates, often among all socioeconomic spheres, have been found in developed countries such as Sweden, Italy and Croatia.

Says Julies: “I’d lie if I say I drank because of poor circumstances. For most of the time I had money. I drank because I wanted to be ‘in’ with my friends. Everyone drank and all we had to do to get alcohol was to walk to one of the nearby shebeens.”

In Roodewal, says FASfacts social worker Michelle Liebenberg, peer pressure within the context of a general binge drinking culture contributes hugely to pregnant women drinking, as well as to parents giving their children alcohol.

“In Roodewal you haven’t drunk ‘right’ if you’re not drunk. Some people argue alcohol is an ‘okay’ choice because it’s not an illegal substance like drugs,” she says. “It’s also cheap.”

Ironically, research has shown that alcohol is the most harmful of all abused substances to unborn babies – more so than cocaine, heroin or dagga. It’s also the most widely used addictive substance in South Africa.

Liebenberg says parents sending their children to buy alcohol on their behalf is commonplace in Roodewal. “It’s become socially acceptable for a child to walk around with a beer. Because the shebeens are unlicensed, there are no rules. Children can easily buy – and drink – alcohol illegally.”

Century-old “legacy”

Although Worcester is in the Cape Winelands and some of Roodewal’s residents work on wine farms as seasonal workers, FASD is by no means limited to areas with wine farms. A recent study in Aurora on the West Coast, a grain-producing region, found rates of 17.5% among schoolgoing children. High rates have also been found in De Aar in the Northern Cape.

But studies do consistently point to the “legacy” of the historically unique relationship this population has had with alcohol. According to FASfacts director Francois Grobbelaar, no farms in the area use the (illegal) dop system, in which workers get paid with wine, which began during Jan van Riebeeck’s time in the Cape.

But he adds: “You can’t expect to eradicate a drinking culture that was nurtured over 200 to 300 years within 20, 30 or even 40 years.”

Uncertainty

Back at her hok, Julies is preparing her children for a Wednesday-evening church service. She smiles: “I tell them about God and pray with them, because I’ve changed my life.”

The mother says it’s now more than a year since she and her children drank alcohol. But Julies’s husband remains a regular binge drinker.

“Yes, it’s difficult with him still drinking,” she says, placing her Bible in her handbag. “But at least he doesn’t hit me any longer because we fight less. The alcohol made me want to argue with him all the time.”

Julies’s husband is working again, albeit for a meagre wage of R1 800 a month at a packing firm. She is now a mentor to pregnant women. Life for the Julies family remains hard; the future is uncertain.

Julies pulls the hok’s door shut and mutters: “Often, when we walk to church on a Sunday, which is still my husband’s biggest drinking day, my son will say: ‘Mammie, Daddy’s drunk all the time. Why don’t we all just start drinking again as well and be one lekker family?'”

* Not their real names