Madala Kunene emerges from the back of a large stage in the middle of a football field in Ulundi, KwaZulu-Natal. A guitar he’s removed from its stand hangs around his neck as he talks about the songs he will sing on stage during his scheduled 40-minute set.

He waits in the wings as one of those typical government-gig emcees announces that Durban kwaito hitmakers Big Nuz have arrived and will perform later in the show, much to the elation of the crowd.

Kunene shuffles over to the young promoter who is wearing stone-washed jeans and a white golf shirt. He whispers a few words before going on stage. It’s musical rush hour and the impatient crowd is feeling boozy. Kunene plugs in and tries to overpower their noise with a slightly up-tempo rendition of his greeting track, Sanibonani.

Trippy youngsters gathered in front of the stage make a circular motion with their hands calling for a substitution. They want Big Nuz. Kunene is booed off stage and does not even get a chance to finish his second song properly.

Kunene (62) is arguably one of South Africa’s greatest guitarists – alive or dead. He lives in Hillary, a newly gentrified suburb just outside Durban. Here five-roomed houses are nestled between double-storey pads and convenience stores. Kunene and his family occupy a modest-sized home that is in desperate need of a paint job. The house is a gift from his former boss, Robert Trunz, head of B+W (later Melt) records.

This is where this blues troubadour’s head hits the pillow as he tries to keep away from prying eyes – particularly those armed with camera, pen and paper like me. “Sometimes you guys make up all kinds of stories,” he says. “I once opened the paper and read that I was quitting music and becoming an inyanga [spiritual healer]. People just pull stories out of thin air and it’s really discouraging.”

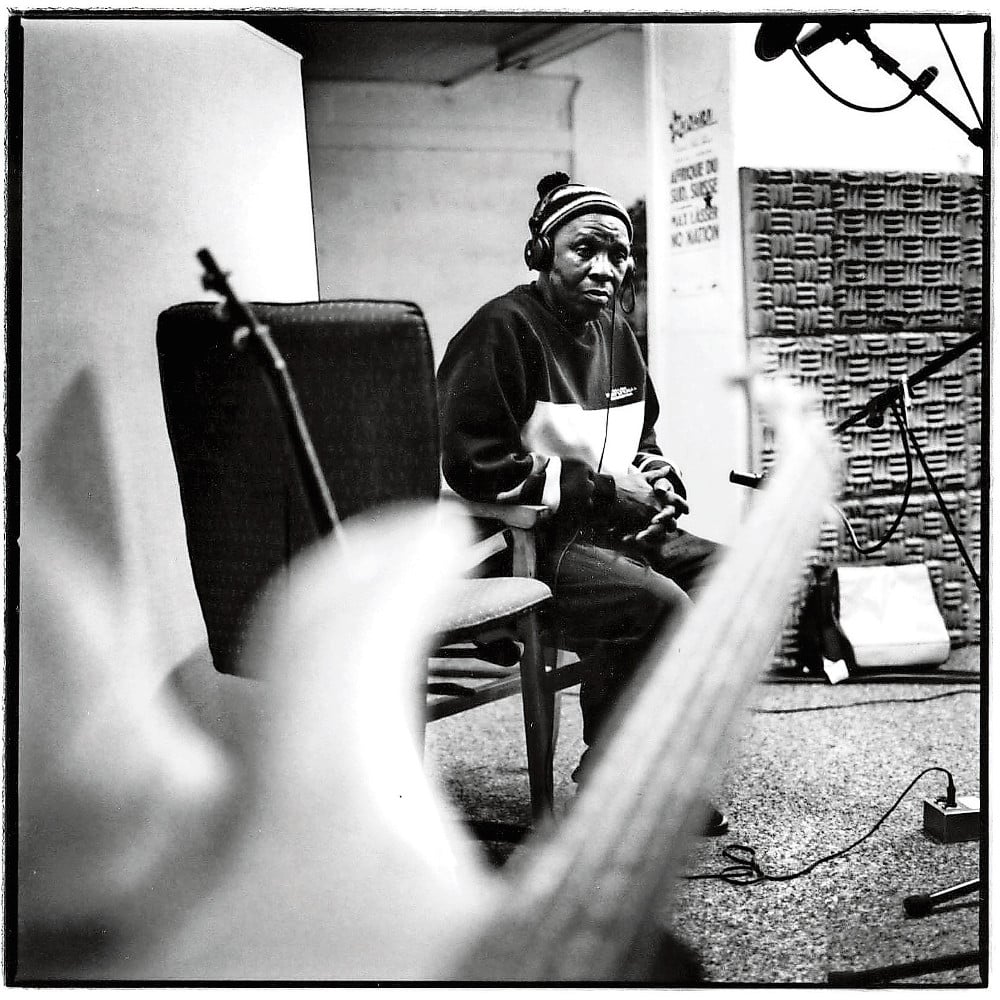

Kunene is wearing light cotton pants with tattered edges and an orange and lime print detail. On top he sports an equally flimsy, maroon floral overcoat over a blue and white shirt. A signature green woollen hat frames his crumpled face.

His weapon of choice is a Takamine six-string guitar with a black neck and a coffee-brown finish. He puts it on a stand next to him before we begin our conversation. This is the axe that Kunene has been riding like lightning across stages for the better part of the past decade. The strings that quiver like antennae from the headstock of the instrument are much like Kunene’s own life story, loose and flexible.

He tells me what he said to the promoter before going on stage on that windy Ulundi afternoon. “I told him he is still gonna have to pay me in full,” he says, before bursting into laughter.

His latest project is a new production at the Durban Playhouse called Bhakti, which merges his music with contemporary dance pieces created by award-winning choreographer Lillian Loots. Speaking about the show, Kunene says it offers him a unique challenge of playing live music to set movements: “I love improvising and being able to play different things, but with this show there are a lot more restrictions and that is a good thing. There is a lot of beauty in a controlled performance and it really pushes me as far as that is concerned.”

The themes of isolation and helplessness in Bhakti merges well with Kunene’s often melancholic and meditative musical sensibility. “It’s interesting to work within a dance framework because suddenly you are not just thinking about yourself and how you play, you are thinking about somebody else. You have to watch them, their movements, and make sure that you don’t mess up and make them miss a step. It’s a lot of pressure but it’s also fun,” he says.

Kunene is one of the most talented and yet obscure musical figures in South Africa’s post-1970s blues lexicon. His music is an acquired taste among hipsters and blues purists, and operates outside the familiar trappings and humdrum of South Africa’s pop idiom. If you consider yourself an alternative, roots-inclined South African music lover, then chances are you have seen or heard Kunene’s name mentioned somewhere, while simultaneously having no specific memory of the face attached to the name.

Kunene is one of the top South African folk-guitar marksmen, a true original and one of KwaZulu-Natal’s musical lighthouses. “It’s strange when people are interested in your music, particularly as a guitarist, because there are so many people who play this instrument at one level or another. As far as uniqueness goes, if you want to stand out, playing the guitar is hard because it’s difficult to distinguish yourself,” he says.

Kunene is often described as a mbaqanga or maskandi artist, a label he hates. He has no interest in genre specifications and prescriptions. Instead, his brand of blues operates in a space where there is a transfusion of cool jazz, maskandi, mbaqanga and East Coast melancholy.

“Music that’s one-dimensional never connects with people,” he says. “I grew up listening to a lot of Duke Ellington and even then I realised that his music was from elsewhere but it also had bits and pieces and sounds that I could recognise from my own life. And that was liberating because it’s allowed me to merge things from different sounds that I like and have ownership of that process.”

In person, as on stage, Kunene, also affectionately known as Bafo (brother), is evasive. He can go for hours in conversation without making much eye contact. Often when he performs he buries himself in the spotlights and looks straight ahead in what seems to be a meditative state. And always with a mischievous smile that proclaims: “This is my thing.” He employs the guitar as a medium for call and response between himself and the audience. On sets he can add entirely new riffs and impromptu adaptations of songs he has already written, depending on the mood of the audience.

During the time we spend together, it becomes clear that the guitar is an extension of Madala’s own personality: he picks it up and breaks into melody, often in mid-conversation, adding sound to the gaps words cannot reach. Where language fails, music will have to suffice.

“I’ve never been really good at talking because talking also requires that you listen and it’s very difficult to express yourself when you’re in dialogue with someone you don’t agree with. That’s why music is so important – it allows you to say things people don’t agree with in a way they like. It eases tensions in a way dialogue just can’t,” he says.

Although a figure of relative anonymity, Kunene is somehow able to get artists to rally around for projects or causes he believes in. Friendships like those he shares with Guy Buttery and Bafana Nhlapho have ensured that he remains active. Recently he’s been recording some new material with BLK JKS drummer Tshepang Ramoba.

A father of nine, Kunene confesses that he doesn’t want to die broke like so many of his musical peers and that’s why he continues to work so hard. These days he doesn’t gig a lot but he gigs better than many.

On an almost yearly basis, he is able to secure tour dates across the seas at festivals in countries such as Germany, the United States, Switzerland and France. At home he is a staple diet in manicured spaces such as Durban’s KZNSA Gallery as well as the Elizabeth Sneddon Theatre at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Anywhere will do to keep his unique brand of the blues alive.