Since time immemorial ancient cultures have carved vast, mystifying designs on the Earth’s surface. Messages to the gods? Astronomical calendars? Landing sites for extraterrestrial visitors? These are geoglyphs, large designs on the ground made from durable materials such as soil and stones.

You find them across the globe, from South America – where Chile’s Atacama Giant lies 119m tall against a barren hillside and the Nazca animal figures that cover 450km2 of Peruvian desert – to Kazakhstan, where Google recently discovered 50 geometrical geoglyphs, including swastikas.

It was the Nazca lines in particular that inspired land artist Anni Snyman to create the Snake Eagle Thinking Path at Matjiesfontein in the Karoo recently. There are no mysteries behind it, however.

“Land art is a way of interacting with the natural world. You don’t have to have a degree in art history to appreciate it,” says Snyman, who is co-founder of Site Specific, a nonprofit group that produces land art events in South Africa to bring meaning to selected sites. In this case, it was in honour of a breeding pair of black-chested snake eagles resident in the area.

Work began in September and finished in February. Unlike in Nazca, where the artists scraped away the darker topsoil to reveal lighter-coloured earth beneath, Snyman and her team of volunteers created their 170m?x?58m design with thickly painted lime dots the size of a small dinner plate. Lime is a natural material that contrasts with the earth, showing up on satellite pictures. Dots evoke Aboriginal paintings as well as South African rock art in which dotted lines depict portals to other dimensions.

Clearly visible from the air if you’re lucky enough to get up there, Snyman’s beautiful, vaguely Native American-styled image is a continuous line that covers 1?536m.

“The Nazca lines seem to be walking lines,” she says. “The act of walking, of making the artwork come alive through your actions, appeals to me. So it’s also linked to the tradition of labyrinths. The sense of your body moving through space in relation to the work and the contextual landscape brings with it an acute awareness of the moment and urges one towards a re-evaluation of human endeavour and, most importantly, time.”

The grid after the wind (Janet Botes)

The grid after the wind (Janet Botes)

A maze of white dots

I walked the Snake Eagle Thinking Path one sharp, blue Karoo morning. From the ground it simply looked like a maze of white dots. The stretch of stony earth where it’s laid out was a British Army campsite during the South African War, housing 10?000 soldiers and 17?000 horses. Popping up among the prickly clumps of Karoo bushes more than 100 years later are fragments of green glass, old ceramics and rusty bully beef tins on some of which the date 1901 is still visible. The art team has turned a few into small artworks. Tiny tributes.

I went at a slow, steady pace, making sure not to tread on the dots – a few are already cracking on the edges – and found myself musing on this specific space at this particular time: wide-open veld and sky, as well as what had gone before, particularly for those unlucky soldiers on the hard, cold ground.

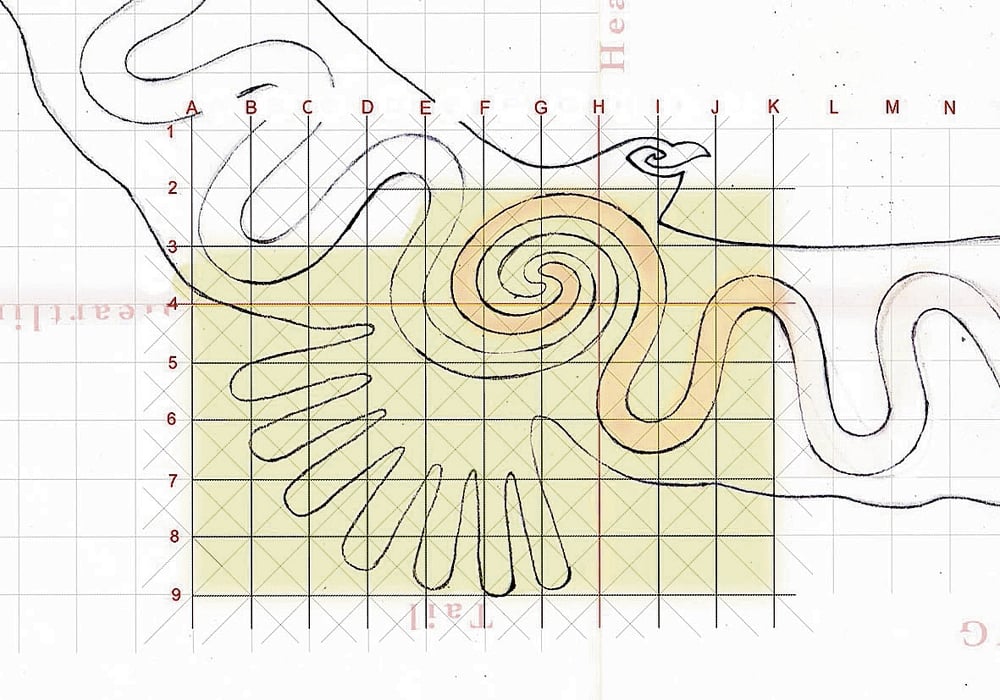

Creating the Snake Eagle was a collaborative process that necessitated transferring Snyman’s drawing to a 6m?x?6m grid with the help of geologists Chris Hartnady and Rowena Hay of the earth sciences consultancy Umvoto Africa, using GPS readings and land surveying tools.

“We redrew the Eagle line within each square,” says Anni, “marking it with lime dust, sweeping plants and rocks out of the path, and replanting bigger bushes wherever possible. Then the lime-dot team moved in. It took about 16 of us three weeks.

“After Lance Foster took aerial pictures with a drone, we could see our half-drawn eagle for the first time, and made corrections.”

A drawing of the Snake Eagle Thinking Path

A drawing of the Snake Eagle Thinking Path

A Karoo canon of geoglyphs

A fine artist and former curator and lecturer, Snyman has been using art objects in nature ever since her first attempt seven years ago at the Afrika Burn festival in the Tankwa Karoo.

There she and her artist brother PC Janse van Rensburg created an Earth Siren geoglyph to call attention to environmentally destructive projects in the Karoo. It can still be seen on Google Earth’s 2009 view of the site.

The Snake Eagle is Snyman’s first permanent geoglyph. “We plan to create a Karoo canon of geoglyphs,” she says. “To walk the geoglyphs of the Great Karoo could become a tourist pilgrimage. We intend to build a Riverine Rabbit in Loxton next year. Volunteers welcome.”

Snyman’s hope is that the Snake Eagle will attract global attention to Matjiesfontein’s unique Victorian history.

The town is a national heritage site and its Lord Milner Hotel, built in 1899, was restored in the 1960s by legendary South African hotelier David Rawdon and recently brought back to vibrant life by another legendary South African hotelier, Liz McGrath, who died last January. Her company, The Collection by Liz McGrath, continues to run the hotel, alongside of which the Snake Eagle Thinking Path is an intriguing addition to Matjiesfontein’s otherworldly charm.