Activist and artist Adejoke Tugbiyele.

United States-born artist Adejoke Tugbiyele, whose sculpture, ink prints and video installation are on display at Cape Town group show Speaking Back, talks to the Mail & Guardian about using her art as a platform for activism and how the passing of Nigeria’s anti-gay laws in 2014 affected her life and art-making. Tugbiyele’s work highlights sexual identity and has been exhibited at the 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair in London and the Centre for Contemporary Art in Lagos, Nigeria.

Your work at Goodman Gallery in Cape Town was created in 2014, around the time when the anti-gay law passed in Nigeria caught the world’s attention. Was your art a reaction to this?

For the exhibition, a set of 10 drawings, sculpture and video was selected from my body of work. I also did a live performance during the show’s opening reception. The ink drawings most directly speak to the way ultraconservative Christian doctrine continues to demonise innocent people who choose to love openly and freely.

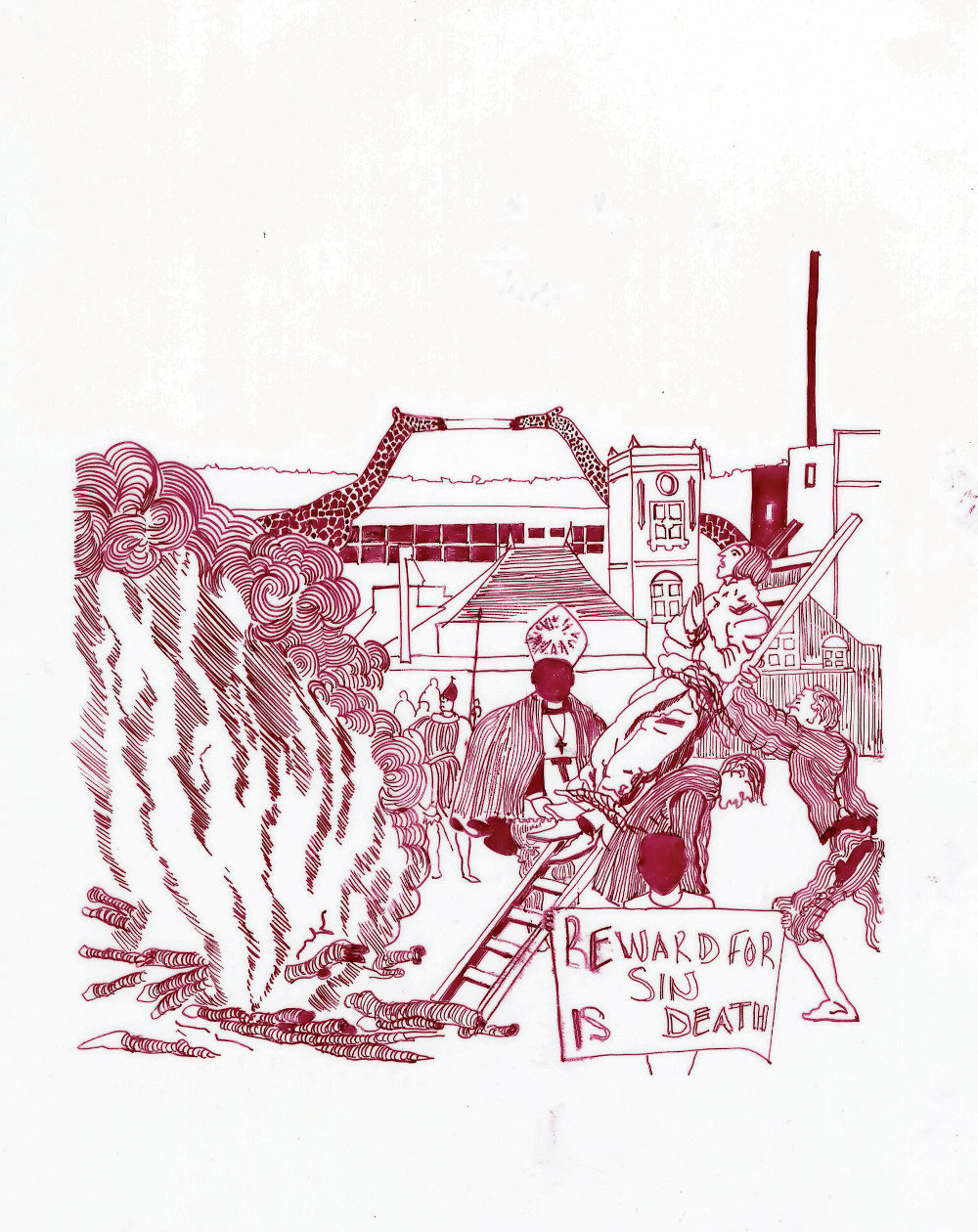

As soon as Nigeria passed its anti-gay law, dubiously called the Same Sex Marriage [Prohibition] Act, I fervently began finishing the set of drawings I had already started. These ink drawings combine imagery from the torture of sodomites in medieval Europe with current journalistic images I found online, depicting anti-gay protests in Africa. By “flattening” space and time in this way, I wanted to show how much humanity has not changed, and how much work needs to be done in Africa with regard to LGBTQ [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer] rights.

What were you doing in Nigeria at the time the laws were passed?

I left for Nigeria in October 2013 to embark on Fulbright research as a scholar and visual artist. I was raised in Lagos for seven of my formative years, and also visited as a young adult. So in many ways the trip was like a homecoming. I was interested in how LGBTQ Nigerians balanced their love of God with self-love, while living in a highly conservative familial and sociopolitical environment.

My work went on smoothly for the first three months. On January 7 2014 the Bill was announced in the media. All of a sudden, homosexuality emerged as a primary conversation topic and tensions were high. Not only did I become emotionally depressed, I started getting ill from high anxiety, lack of sleep and loss of appetite. My response was to make art, or rather quickly finish what I had already started.

Adejoke Tugbiyele’s Reward for Sin is Death

Speaking of the title of the exhibition – Speaking Back – curator Natasha Becker told me she “wanted it to be about what women artists are saying ”. In this show, what is your art saying?

The reality of death, torture, pain, jealousy, fear is so real among many LGBTQ Africans. Many people don’t realise that the coming-out experience is torture enough. My work speaks to this inner struggle, but also to how the body navigates burdens of family, religion and the state. In South Africa, the activist and photo-grapher Zanele Muholi has sacrificed so much and worked hard to show how real the pain is for lesbians who endure abuse in the form of “corrective rape”. This happens in Nigeria as well but few women speak up about it. Until Nigeria’s anti-gay law is eliminated, it will continue to motivate my work.

For those of us who weren’t at the show’s opening, could you share with us the thoughts around your performance piece?

The body remains the stage, the site of institutional control and thus [is] where we need to look to not just exercise but demand freedom. For me it begins with how I dress each morning to daily mannerisms of my life/work as an artist. This is what my performance Freedom Dance suggests. So long as we are alive, let’s dance. In Nigeria, at the end of birthday, wedding and funeral celebrations there is a call to Dance! Dance! Dance! Just look at the printed programme of any official celebration and you will see those words at the very end.

We dance to remind ourselves that we are alive and that life itself ought to be celebrated.

Second, my decision to dance in Nigerian men’s traditional attire, or agbada, played with gender roles. I also danced to prerecorded traditional drumming, that I also played to challenge the patriarchal notion that only men should drum. My aim was to interrogate gender roles in Nigeria. The point of the performance was to demystify ideas of male and female, without needing to categorise the body in terms of “gay” and “lesbian”.

What are your thoughts on using your art as a platform for activism?

I find the relationship between my art and activism to be cyclical. Activism helps me stay in touch with the issues and ideas I respond to in my work. My work in turn educates and empowers others in the LGBTQ movement in Nigeria and beyond. Both depend on each other. To me, political art is not as powerful when it operates in a vacuum. It must engage people and serve as a call to action. Artists do not make laws and policies, but they can inspire policy makers by bringing visibility to issues concerning the marginalised.

Where are you currently based and what other projects are you embarking on now and in future?

I am establishing my practice in New York, with additional studios in other locales in order to engage different communities, such as Lagos, Johannesburg and Newark – at different times and for different reasons. Coming up soon is both New York City Pride and Newark Pride, in which I will participate to support and recognise the LGBTQ community in Nigeria and the diaspora.

I am excited to announce my upcoming solo exhibition at Goodman Gallery, Cape Town, in September 2015, curated by Neil Dundas and Lara Koseff, as well as an art residency in Maboneng Arts District in Johannesburg.