SA fiction is still muddling along ... what followed after 1994 was pretty much a randomised free-for-all.

In one of the many post-Franschhoek Literary Festival debates that have taken place around the idea of decolonising literature, it is perhaps Sunday Times books editor Ben Williams who cut to the chase. He described the so-called “white literary system” – the one Thando Mgqolozana had vowed to opt out of in a heated panel discussion at the festival – as imposing an “ambiguity of dependence”. Once one is immersed in it, Williams said, “one can’t move in any direction unambiguously”.

It was quite soon after Mgqolozana began speaking at a Wits University discussion around “decolonising the literary landscape” that it became apparent that he too could not move in any direction unambiguously. Mgqolozana said: “I wish I was taking a stand not to be published by Jacana … I cannot change those things.” But his 21 tweeted suggestions, which have become something of his manifesto for decolonising the South African literary scene, begin by declaring that “starting our own thing [a whole new literary infrastructure] is the only way”.

Mgqolozana’s main points in this regard are that the power to change things lies not necessarily with black writers but with readers and book buyers. He suggests, to get books into townships, using a model based on the existing distribution system to shebeens that also draws on the abundant ingenuity of township dwellers. But he also sounded a warning: private individuals alone cannot deliver what’s required.

Williams, also the founder of bookslive.co.za, was present when Mgqolozana made his Jacana remarks and emphasised that ambiguity is evident in a lot of South Africa’s economies. “It’s a feature of our society. Our markets are small and it’s difficult to make a break with a system and exist outside of those dependencies because they are also legitimising forces. You can get ahead quickly inside of them.

“Radical action is needed to create ruptures and realignments. It’s a question of how quickly these realignments happen. It is similar to what has been happening on the campuses with the #RhodesMustFall movement. Some of it is symbolic, but the Rhodes statue has gone and that happened quite swiftly.”

Williams said that since Mgqolozana was talking about “black literary self-determination”, there was no way to do that without government involvement. “In France, for example, you can make a living as a writer partly because the cultural system that enables writing is held up by the government. In all forms of cultural production, the government mandates certain quotas to be met and there’s a robust grant system so you can access funding. It’s kept French culture afloat from the tide coming across the channel.”

Williams said there are some lessons to be learnt in some of the things the apartheid government did to promote Afrikaans literary self-determination.

Mzi Mngadi, a Pietermaritzburg-based author who publishes in isiZulu, said the National Party government did some damage in that “it made us to look down on our languages as only being worthy of creating prose books for schools.

“They made millions for themselves but they did not actually promote a reading culture. They had a sure-case market for books.”

Mngadi, whose book Ababulali Benyathi is prescribed for first-language isiZulu speakers in matric, believes that one of the ways the new government can promote a culture of reading is by promoting the adaptation of novels into screenplays. “An example of this is the book Tsotsi [by Athol Fugard, which was turned into an Oscar-winning film]. I wasn’t aware of the novel and I can tell you I was not alone in going to the shelf to read it. Before the TV era, it was fashionable to have a copy of James Hadley Chase in your back pocket.

“The libraries in our cities only stock old and dilapidated books when it comes to indigenous languages. In their own defence, though, they may just say that people don’t request those books, but people can’t request or buy something they don’t know [about].”

Contributing to the debate, author Pumla Dineo Gqola argued that even as “decolonialisation” was being discussed, people were still committed to a model that needed to be slashed. Gqola counted Femrite, the nongovernmental organisation promoting women’s writing in Uganda, and Cassava Republic, the publishing imprint based in Nigeria, as examples of where “imagining had been imaginative”.

Publishing houses are not transformed, Gqola said, and aspects such as editing and social media are run by white people and thus “black people would always be anthropological subjects”.

Agreeing with Gqola was Durban-based Xubera Institute for Research and Development director Xolani Dube. The institute’s format is to host discussions and book launches where patrons pay an entrance fee for a chance to mingle with authors.

“Most English-language writers that are Africans are products of Western education, living through handouts of the Western education system. Their craft is not about representing the narrative of Africans and hence this debate is about their rejection by this system. Kwesi Prah has never gone to Franschhoek and cried. Pitika Ntuli has written a lot but he’s never come back from somewhere crying.

“Writers working in isiZulu, isi-Xhosa, Setswana etcetera, they understand that they are not communicating to whites or Western scholars but they are writing to their people. In South Africa you have to demonise a particular race to get an audience, but then you do so in the language and manner of the race you demonise.”

As the bookshop declines, if Gqola is to be believed, perhaps the model to study would be one pursued by authors who have “hacked the system” such as Gayton McKenzie, DJ Sbu and Mofenyi Malepe, author of motivational tract-cum-memoir 283: The Bad Sex Bet.

Written in the form of a “letter to my son”, Malepe’s cautionary tale about sexual indiscretion was officially released for consumption on World Aids Day last year. Malepe, who regularly wears the title’s paraphernalia, said the initial print run of 5?000 books is about 600 copies from depletion. The marketing drive is aided by gaudy, porn-like cover art and a marketing team of five vehicles bearing the book’s artwork.

“I wouldn’t say we’ve been successful,” says a confident Malepe. “The goal is to sell a million copies. The thing with publishers here is they take the books to Exclusive Books and authors think they have it made and they relax. If these writers did what I did, they’d make it.”

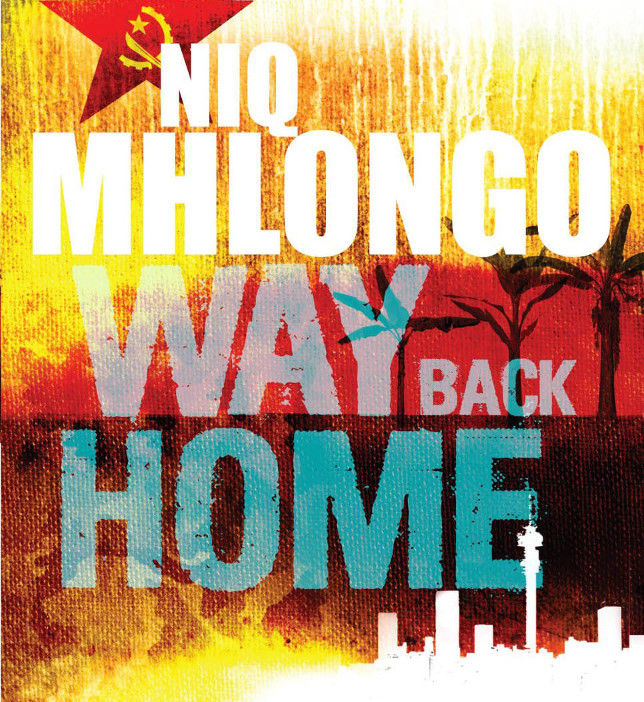

Malepe believed that the underlying social campaign (to mend bridges between fathers and sons) gave his book added impetus, especially in neighbouring countries, but he believed the same marketing strategy was replicable to drive fiction sales in this country. “If you’ve ever read the book Way Back Home by Niq Mhlongo, the characters there, I know each and every one of them. My feeling is that readers don’t really care, they just want to read.”

Ironically, it was Sihle Khumalo, the author of the 20?000-plus-selling travel book Dark Continent My Black Arse, who differed with Malepe, arguing that, as a nation, we just don’t take literature seriously. “The fact that the biggest literary award in this country is R100?000 proves that literature is just not a priority.”

According to his publishers (Umuzi) it was a combination of wit, charisma, a catchy title, the novelty factor but most of all word of mouth that combined to make Dark Continent the smash that it was. Khumalo’s other travel titles for the imprint never quite came close to repeating that first feat, suggesting that a formula may very well lie outside of tried conventions.