For well over a generation the management of diabetes focused primarily on bringing blood sugar levels within the normal range to prevent a huge list of complications such as blindness, kidney disease, heart attacks, strokes and amputations.

‘Do as I say, not as I do” has long been the mantra of doctors. But newly emerging data from the Discovery Vitality Group strongly suggests that it should be “do as the doctor does”.

Chronic disease’s impact

The financial health burden is increasing worldwide, especially for chronic illness such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancers. The increase in chronic disease can be partially attributed to an ageing population, but four risk factors – unhealthy diet, smoking, excess alcohol use and a lack of physical activity – account for the majority of behaviours leading to chronic diseases.

Data from the 2010 global burden of disease study for South Africa showed that six of the top 10 leading risks for all diseases are lifestyle behaviours including (in order of importance) alcohol use, poor diet, smoking, suboptimal breast-feeding, insufficient physical activity and drug use.

Three of the other four risks are directly influenced by these behaviours: obesity, high blood pressure and high glucose levels. We explore how general practitioners in particular could influence healthy behaviours of their patients by starting with themselves.

Why prevention is important

Chronic diseases account for 75% of the global burden of disease, according to a 2011 report on the global economic burden of non-communicable diseases by the World Economic Forum and the Harvard School of Public Health.

In 2012 cardiovascular mortality rates of the working-age South African population were higher than in similarly aged people in the United States and were predicted to increase by 41% between 2000 and 2030, the South Africa Centre of Excellence associated with the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute found. In addition, they report that nearly half the deaths in South Africa caused by cardiovascular disease occur before the age of 65 – four times the US rate, with a major effect on the economy.

The prevention of chronic disease could bring substantial cost and health benefits, but few large studies have quantified this. Lifestyle interventions are effective; according to a 2010 study published in the American Journal of Health Promotion, involving about one million Discovery members, those who were highly active in health promotion programmes tackling smoking, exercise and diet had lower costs per patient, fewer hospital admissions and shorter stays in hospital when compared with other members who were either less active in the same programmes or not at all.

Another of our US-based studies focused on the theoretical effect of workplace health promotion programmes on costs among our insured members. By reducing risk factors for chronic disease, employers could see average medical costs slashed by more than 18% for insured employees, according to a 2014 study published in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. And further cost savings are expected from increased morale and productivity, and reduced absenteeism.

Doctor’s role in prevention

The doctor’s role is traditionally seen as diagnosing disease and providing appropriate treatment, most often pharmacological-based. However, as the “custodian” of health, the doctor can also be key in the prevention of chronic disease and encouraging the uptake of other forms of treatment such as lifestyle change.

Missed opportunities for prevention in general practice settings are common. Despite substantial benefits and generally low treatment costs, the World Health Organisation has shown that appropriate measures for prevention after heart attacks – medicine use and modified lifestyle-related risk behaviours – are implemented in less than half of all patients, even in high-income countries.

How do doctors influence the lifestyle behaviour of their patients? Factors we have long known influence a patient receiving – and being influenced by – prevention advice include their age, sex, level of education and their ability to pay for medication. Emerging evidence suggests that the influence of a doctor on his patient goes beyond treatments provided and also considerably influences the patient’s lifestyle. Doctors have a certain responsibility in terms of their public image – most patients expect their doctors to lead healthy lifestyles and, intuitively, the doctors’ approach to a healthy lifestyle will affect his or her ability to change patients’ behaviours. This is understudied, however.

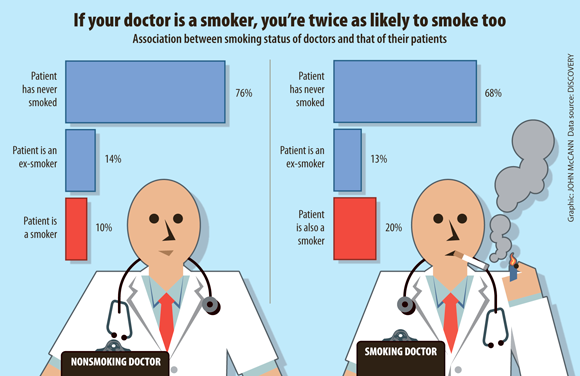

Data presented at our Doctor Thought Leadership Summit on July 12 and 13 showed that doctors may have more influence on their patients than they realise: smoking rates among patients of doctors in our network who are nonsmokers are about 10%, compared with 20% among patients of doctors who are smokers. Similarly for exercise, inactive doctors had more physically inactive patients (about 56%) compared with doctors who were highly active (about 50%).

Vitality age is a measure of health status and factors in lifestyle, blood tests, body weight and blood pressure. The difference between an individual’s actual age and their Vitality age (the Vitality age differential) can give a good indication of overall health status.

The data showed that patients’ Vitality age differentials were positively associated with that of their doctors.

Increasing influence

Achieving behaviour change is complex with numerous challenges because patients have a natural resistance to changing long-held habits.

Feedback is important to sustain positive behaviours and the long lag between the healthy intervention and measurable health outcomes is an obstacle that can be tackled with shorter-term, intermediate feedback of improved health outcomes and the use of technology such as wearable health-tracking devices to provide near-term information to the patient.

Health “points” might be issued for healthy behaviour, such as healthy food purchases and gym use. The points can then be converted into rewards: movie tickets, travel discounts, special offers on sports gear.

How can doctors ensure that they are providing the motivation and skills needed by patients to change their behaviour?

Our own data suggests that doctors should start by reflecting a healthy image themselves to positively influence the patients’ likelihood of achieving a healthy lifestyle. We are working on ways to encourage doctors to focus on prevention.

The output report of the Lancet-Rockefeller Foundation Commission on Planetary Health was recently released, including a call for doctors to encourage healthy diets and activity as a way to promote population and environmental health, and sustainable living.

Should doctors be trained to better influence their patients’ lifestyle choices? A 2010 study, in the Journal of Medical Education, reported how they used actors to rate general practitioner performance in real-life consultations of childhood obesity patients and found that the actors’ ratings of the consultations, but not the general practitioner self-ratings, predicted reductions in body weight even nine months after the visit.

Such simulations should be considered to identify doctors who require further behaviour change technique training and, while 95% of general practitioners rated such exercises as useful, only 18% would pay for them. In addition, institutions should focus on the health of their staff through their own workplace wellness initiatives, as discussed earlier.

Finally, doctors should remember that they have influence as advocates for health beyond the usual setting of the doctor-patient consultation. This has led to positive change as seen with dramatic reductions in rates of smoking among doctors and their patients in Britain.

Leading by example, doctors have a particularly unique opportunity to improve patients’ health by embracing sustainable lifestyles as well as by prescribing lifestyle interventions.

Derek Yach and Cother Hajat work for Discovery, which owns Discovery Health (the largest administrator of medical schemes in South Africa) and Vitality. Yach is also a member of the Lancet-Rockefeller Foundation Planetary Health Commission