The sun has just risen over the shacks of Extension 1 in Diepsloot, Johannesburg north. It is a calm Tuesday, just after 6am, in October 2013. Those with jobs are on their way to work; most people are hanging around doing nothing, whispering about death.

A crowd of people are banging on the door of Sisanda and Thokozani Mali’s one-room tin shack. “You need to come to the toilets! Quickly!” a voice shouts on the other side of the door.

The young mothers race to the public toilets, about 500m away, still in their pyjamas.

“It’s the one on the left; the one that’s broken!” someone yells. “They were found in there.”

The Mali sisters push through a heaving crowd of bodies to get to the toilet. Their hearts are hammering. They can hardly breathe.

At the toilet’s tin door, someone announces: “People have found the bodies of two toddlers. They may be yours.”

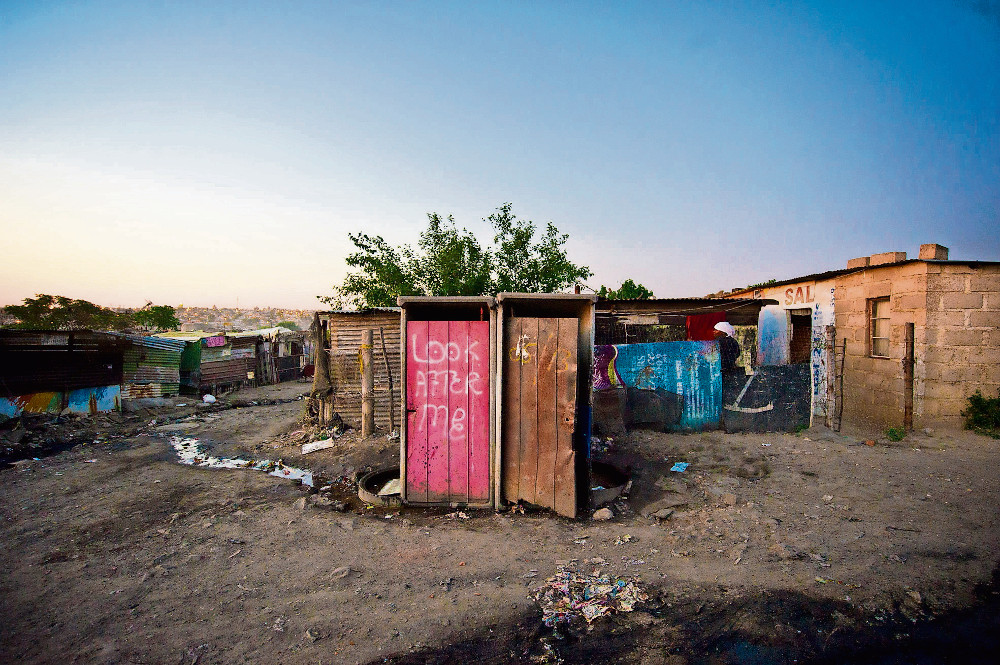

The Mali cousins’ bodies were found stuffed down these toilets.

The Mali cousins’ bodies were found stuffed down these toilets.

Missing toddlers

Four days earlier, two of the Mali sisters’ children had disappeared a few metres from the family’s doorstep. They shared the shack with their mothers, grandmother, great-grandmother, aunt and five-year-old cousin.

Just after lunchtime, Sisanda had gone to buy sugar from a nearby shop. Her three-year-old daughter, Zandile, and Thokazani’s two-year-old, Yonelisa, were playing in front of the family’s shack. When Sisanda returned, the girls were gone.

“No one saw anyone talking to the children,” Sisanda remembers. “But there were some people who told us something that made us worried. They said: ‘We saw them walking behind a man wearing a yellow T-shirt.’ “

After they had reported the disappearance, the police, Mali family and community members combed thousands of shacks and alleys. They scoured the rubbish dumps and riverbanks.

But on that Tuesday morning the search stopped.

Two tiny, mutilated bodies had been found – they were stuffed head-first into a blocked public toilet. The four little feet and legs that stuck out were tied together with plastic, and bodily fluids poured from the corpses, which had started to decompose.

There, amid the stench of faeces and urine, someone turned the small, half-naked bodies around so that the Mali sisters could see their faces.

“It was our daughters,” recalls Sisanda.

A year later, Ntokozo Hadebe, who was 29 at the time, was found guilty on six rape and three murder charges – in addition to the rape and murder of Zandile and Yonelisa, DNA results also linked him to the disappearance of another girl, a five-year-old, whose body had been found on a rubbish dump in the area. Post-mortem results revealed he had raped each girl twice – vaginally and anally – and then strangled them.

Hadebe’s shack was about 20m from the toilets where the girls were found.

When the judge passed the sentence – 240 years of imprisonment – in the high court in Pretoria, Hadebe showed no remorse. “Fuck you!” he repeatedly shouted before being led down to the cells.

The Mali family has since moved to Extension 9 in Diepsloot, where they’re renting two small rooms at R1 000 a month each. There’s a huge fence, with a locked gate, around the property. “We can’t really afford it, but we need a safe place for the children,” Sisanda explains, adding that Thokozani has since had another child.

Sisanda’s sitting on a couch next to her mother in one of the rooms. There’s a picture of Zandile in a light blue dress next to the pots on the kitchen unit. “We don’t understand why the guy took the kids and killed them like this. He never said in the court why he did it,” says Sisanda softly, weeping. “We never spoke with the killer. He’s not a human being to us.”

On the corner of William Nicol Drive and Diepsloot Road, just after you pass Afri Tombstones, there’s a spanking-new two-storey brick building. Its gloss makes it incongruent with the township. The Diepsloot police station, most of it built five years ago at a cost of R52-million, remains largely unstaffed.

Inside, there’s a spacious charge office, an investigators’ bureau, interrogation rooms and holding cells.

Police officer Lwandile Skosana* thought he would be working here. But instead, he and his colleagues are “squatting” at the nearby cramped offices they are forced to share with the metro police.

There’s no official explanation about why the new police station is largely empty, other than vague utterances from the South African Police Service about “problems with the contractors”.

Skosana says his dream of preventing crime has come to nothing. “Who am I helping here in Diepsloot?” he asks, his voice desperate. “All I do is to drive from crime scene to crime scene, fill out reports and pick up dead bodies. Sometimes I feel like I’m wasting my life here.”

Skosana is navigating his way through one of Extension 1’s narrow gravel roads. The morning’s rain has turned the soil into dark, wet mud. Urine and excrement have collected in the puddles surrounding the policeman. “When I was new in Diepsloot, I used to feel something. But I just feel nothing now,” he says. “Child rape is something that I see almost every day.”

The shacks are built almost literally on top of one another. People are screaming and shouting, and children are running around directionlessly through the incessant, chaotic noise of the hooting of taxis.

Skosana explains: “It’s easy to rape in a place of chaos, easy to drag kids and women into a shack and rape them and hide them away in the mess of Diepsloot. It’s easy for criminals to disappear in this congestion.”

There are no recent statistics for Diepsloot’s official population. South Africa’s 2011 census found the township’s 13 extensions had a total of 137 954 residents. But, four years later, those who live here, including Skosana, believe the number has grown closer to 600 000.

Easy to hide

Skosana stops in front of a shack in which an illegal shebeen operates. “Criminals who need a place to hide, they come to Diepsloot.

“We are all just squeezed together here,” he says and picks up a rolling football to hand it to a boy running after it.

Everywhere, men and women are sitting around. A boy and girl play with a plastic scooter. On the wall of a cellphone repair shop the word “SEX” is scrawled in purple capital letters. Below it drips another phrase: “Life is shit.”

The 2011 census found that only about half of Diepsloot’s inhabitants have jobs. But again, Skosana believes, it’s “much less”.

“When people are bored, they’re dangerous,” he warns. “For some men here, rape has become like a sport – a form of entertainment, like a hobby. And alcohol, which is available everywhere in Diepsloot from shebeens and spaza shops, fuels it.”

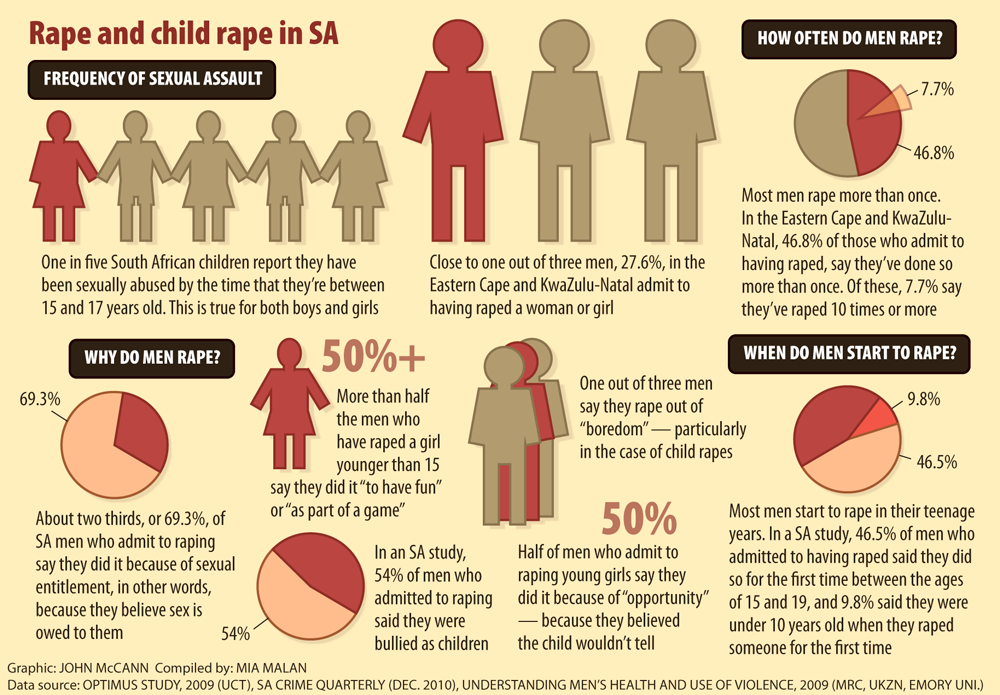

The policeman’s statements are not unsubstantiated. In a 2010 study published in the South African Crime Quarterly, men who admitted to raping were asked their reasons for doing so. More than half of those who had raped a girl younger than 15 said they did so “to have fun” or “as part of a game”.

“Boredom” was an explanation for a third of rapes, and was an even more common motivation when children were raped.

Although the study didn’t find alcohol to be a cause of rape, it found it to be an important “contextual factor”.

One out of three men revealed there had been no consequences for their rapes and did not show remorse for their actions. Only one in eight of the men who had raped were jailed.

Since last month, a few police members have begun to fill up the new police station. They’re too few to occupy even half the building and most of the staff is administrative.

“It’s impossible to police a big place like Diepsloot properly at the moment,” Skosana says. “Usually this entire place is being patrolled by only two police vehicles – there are only two staff members in each vehicle. How can four policemen be responsible for 600 000 people?”

Vulnerable: Thuso Kgosi* has Down’s syndrome and has been repeatedly abused.

Easy target

Thuso Kgosi’s* face lights up as he sits on a double bed in his mother’s shack. Next to him, a rickety table holds a small television that plays the signature song of his favourite soap opera, Skeem Saam. It’s 6:30pm and his mother is cooking samp and beans.

“There’s a boy loving a girl in this programme!” Thuso shouts with his arms up in the air, giggling. “Mangolisa is the boy and Lelo is the girl.”

Naledi Kgosi* and her four children live in this one-room shack in the backyard of someone’s RDP house in Extension 2. There are five other shacks on the same property.

Thuso is different from her other children. He has Down’s syndrome. He looks about 13 – three years younger than his true age.

Twice a week, Naledi works as a domestic worker in Fourways, an affluent suburb barely 10km from Diepsloot. One evening, about five months ago, when Naledi returned from work, Thuso complained of constipation. His mother wanted to help him by using a “traditional cure” of inserting a stick in his anus “to loosen up things”.

But before doing so, she noticed that his anus was “very, very red and swollen”.

Naledi turns around where she’s cooking and places her hands on her hips. “I asked him if he was sore and he told me, ‘There’s this man who is putting his penis in my anus. Every time he does that he gives me 20 cents.'”

Naledi sits on a rusted collapsible chair. She looks at Thuso. “I know this man did this to my son because my son’s mentally disabled. The perpetrator knows the law will not trust my son’s word against his,” she sighs.

The rapist lives just up the road, about 150m from the Kgosis’ home. The morning after she discovered Thuso had been violated, Naledi reported it to the Diepsloot police. “They promised they would investigate the case. But I have heard nothing from the police since and no one has been arrested.”

Throughout Diepsloot, that’s a familiar refrain.

Naledi gets up to give the samp and beans a stir. “I don’t know how many times this man has raped Thuso,” she laments, and knocks the spoon on the side of the pot to clean it. “This thing is filling me with pain, especially since Thuso told me once, ‘Mommy, you know, I was starting to enjoy that sex thing.’ “

She bends over and cries.

Like most mothers in Diepsloot, Naledi is a single parent. The fathers of her children play no role in their lives. “I must cope with this alone now,” she says. “I wanted to tell Thuso’s father about this, but whenever I try to speak with him on the phone he just puts it off. He’s not interested.”

Lone voice: Brown Lekekela of The Green Door acts as a link between victims, medical care and the police.

Lone voice: Brown Lekekela of The Green Door acts as a link between victims, medical care and the police.

Absent fathers

Brown Lekekela, a well-spoken man in his early 30s, eases behind his small desk in the Wendy house in his backyard.

“What leads to a lot of Diepsloot’s problems is that children here grow up without fatherly love,” he says. “Diepsloot’s children put their trust in strangers who can abuse them. To them, they are not strangers, they are their uncles, because they give them five bob, buy them sweets – things that their fathers never did.”

Across from Lekekela is a neat single bed. A paper poster of a blond, turquoise-eyed Jesus is up on the wall. Rainbow rays shine out of Christ’s heart. A statue of the Virgin Mary wearing a baby-blue cloak watches over the cottage from the top of a chest of drawers in the opposite corner.

This is the makeshift headquarters of the Green Door, which Lekekela manages. It helps abused women and children to report the crimes against them to the police, and to get healthcare.

Lekekela is the Green Door’s only counsellor.

“Many child rapes in Diepsloot don’t get reported because children – and often adults too – think this is the way that men are meant to treat kids. Rape is a normal part of life here,” he says.

On Lekekela’s desk there’s a file filled with certificates of counselling and project management courses he has completed. He frequently works through the night. His is often the first kind face that those who have been raped, see. He is the link between them and the police and the hospital.

But Lekekela doesn’t get paid to run the Green Door. The organisation receives no funding.

“The provincial government helped us with this building, about two years ago. Since then the officials come here, they ask what we need, I tell them, they fill in forms, they leave. But no money comes,” he says softly, and incongruously smiles.

No remorse

“Mostly, rapists here don’t think they’ve done anything wrong. They think it’s their right to rape. They argue, ‘What is the problem if I have given this child or woman money?’ “

Lekekela fetches a journal. In it are the names and contact details of people the Green Door has helped. There are many, written in different shades of ink.

“When children and women come here, they still smell like the rapist’s sweat,” he explains. “They will be bleeding and would have scars all over their faces and their private parts would regularly be torn apart.”

He opens the book and shakes his head. “It’s absolutely terrible.”

Most victims have one thing in common: they come from single-parent households. “It’s rare to find a family in Diepsloot headed by a father. They mostly don’t hang around. They leave the children with the mothers – like, its women’s work to look after babies,” he says, scoffing.

In South Africa, it’s unusual for children to live with both biological parents.

According to Statistics South Africa, only 36.4% of children experience life with two parents. When black children are isolated in this research, that figure is even lower: fewer than one out of three black youngsters (31%) stay with their mothers and fathers.

There are no official figures available for Diepsloot but Lekekela believes the proportion of children growing up in households with two parents is “considerably lower” than the national estimate.

“Come with me today and we visit random homes and I can guarantee you almost 100% that in eight out of 10 we will not find the father,” he says emphatically.

The Mali cousins’ fathers didn’t even attend their funerals.

The Mali cousins’ fathers didn’t even attend their funerals.

The murdered toddlers, Zanele and Yonelisa Mali, never knew their fathers. They made zero financial contributions to their wellbeing, and never even attended their funerals, say their mothers.

The man who killed the Mali cousins also grew up without a father. In mitigation of his sentence, he pointed out that he was raised by his grandmother and was left “heartbroken” when his father denied paternity. Molested 16-year-old Thuso’s father last made contact with him in 2004. He has never paid child maintenance.

A fatherless community, according to a 2009 Medical Research Council (MRC) policy brief, gives rise to “intergenerational cycling of violence”. Studies have repeatedly shown that children raised by one parent are far more likely to experience emotional or physical abuse than those who have two parent figures. But, at the same time, research has also revealed that children who have been abused are more likely to become abusers themselves.

The MRC document explains the vicious circle: “Girls exposed to physical, sexual and emotional trauma as children are at increased risk of revictimisation as adults” and “exposure of boys to abuse, neglect or sexual violence in childhood greatly increases the chance of their being violent as adolescents and adults”.

In 2009, the MRC was the joint author of a study conducted among men in the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal. One out of three men admitted to having raped a woman or girl. More than half of them reported they had been harassed or bullied as children. Most rapists also perceived their parents to be “significantly less kind”.

Absent fathers

Back in Diepsloot, Glenys van Halter has been working with sexually abused children for 25 years. She’s a feisty lay counsellor and “creative therapist”, using art to help victims to deal with their emotions.

A few months ago, Van Halter was working at a primary school in the township when a lot of noise emanated from a classroom where a teacher had briefly left the pupils alone. Van Halter went to investigate.

As she entered the room, she saw an eight-year-old boy standing in front of a girl of the same age. He was trying to force her to her knees. His trousers were down.

”He had her by the hair and was smacking her and shouting, ‘You will suck this because I want to know!’ ” Van Halter recalls.

She says she demanded of the boy: “What do you want to know?” He answered: “At home tonight I have to do this. So I want to know what it feels like.”

Van Halter explains: “Those same absent fathers are the rapists and guys who end up in jail. And so it’s perpetuated generation after generation after generation, because the men who do this had no good role models themselves. They grew up watching their fathers and uncles doing the same thing.”

Van Halter later found out the boy was sharing a shack with five adult men who had all been “using him for sex. He was just curious. What was he learning every day?” she asks. “He was learning to abuse others. His role models were five sexual predators.”

Victimised: Five-year-old Murendeni Ramovha* by a 16-year-old. His mother says she knows who did it, but the police hasn’t arrested him.

Victimised: Five-year-old Murendeni Ramovha* by a 16-year-old. His mother says she knows who did it, but the police hasn’t arrested him.

It’s a few minutes after 3pm and a shy five-year-old Murendeni Ramovha* has just woken from his afternoon sleep. He sits in a corner of the only room at his daycare centre in Extension 9 and picks his nose.

The room is about 3m long and 2m wide and holds 20 preschool children. His mother pays R300 a month for his care here.

Murendeni’s parents are from Limpopo – almost a third of Diepsloot’s residents are, according to the 2011 census.

One Saturday afternoon in March, the boy was playing football in the street outside his parents’ RDP house, when a neighbour’s 16-year- old son called him to “show him something inside” his home. About 20 minutes later, a traumatised Murendeni left the teenager’s house screaming and sprinted straight to his parents’ house. “He shouted, ‘That boy took his penis and put it in my bum, Mama. He hurt me!’ ” his mother recalls.

Tears were streaming down Murendeni’s cheeks. His anus was bleeding badly and he urgently needed a doctor. But Diepsloot has no public hospital and his parents, both jobless, couldn’t afford any of the private healthcare facilities in adjacent Fourways. The closest children’s hospital was 30km away – an hour-and-a-half-long round trip, which requires two minibus taxi rides. It cost the three of them R150.

At the Rahima Moosa Mother and Child Hospital in Coronationville, doctors confirmed the rape, treated Murendeni’s wounds and counselled the boy. It would be his only counselling session because his parents can’t afford to travel back to the hospital.

“My son was raped by someone who is still a child himself,” Murendeni’s mother says, crying. “I don’t understand how that could happen.”

But research has proven that this type of rape is not unusual. Asked about their age the first time they raped, nearly half of the participants in a 2009 MRC, University of KwaZulu-Natal and Emory University study said they did so between the ages of 15 and 19. About 10% said they were 10 years old or younger, and 16.4% were between 10 and 14 years old.

Earlier this year, South Africa’s first-ever representative data on child abuse was published in the University of Cape Town’s Optimus study. The research found that, by the time children are between 15 and 17 years old, “one in five report having experienced some form of sexual abuse”.

This was true of both boys and girls.

The morning after their son was raped, Murendeni’s parents reported it to the Diepsloot police. They provided the police officer with the name and address of the boy who had raped their child. But no one has been arrested.

“Now he’s free to rape other children and maybe even rape my son again,” his mother cries. “There’s no justice in Diepsloot. Maybe Satan is in control here.”

‘Many many’ children are buried in Diepsloot’s graveyard, says the caretaker.

‘Many many’ children are buried in Diepsloot’s graveyard, says the caretaker.

Next to a row of open graves at the Diepsloot cemetery in Ridge Road in Extension 5, a cold wind stirs red dust and flaps the wrinkled cover of a discarded magazine. A faded Kim Kardashian pouts on the cover. At the entrance, a blocked drain overflows with faeces and urine; nearby thieves burn stolen cables for the copper.

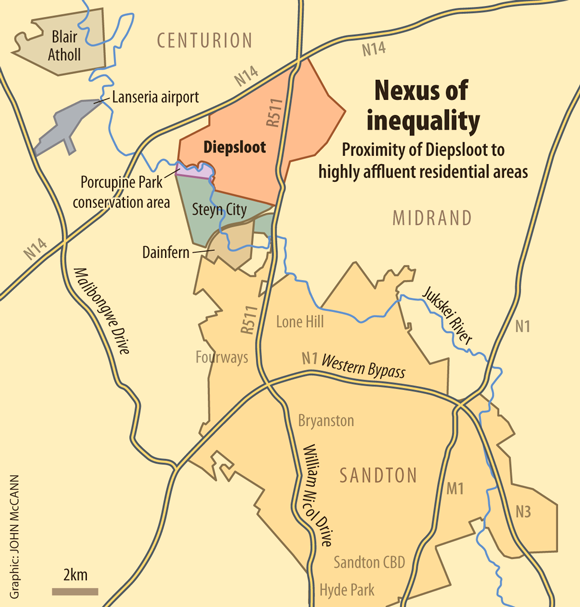

In the distance are the massive yellow and red silhouettes of the cranes constructing Steyn City, the multibillion-rand development that will soon be South Africa’s largest parkland residence, with golf courses, shopping centres, private schools, restaurants and myriad security measures.

“This kind of inequality is very bad for South Africa,” says the Green Door’s Brown Lekekela, gazing from a bridge at the behemoth growing up in the shadow of Diepsloot. “The people here have nothing but then they look down the road at people who have everything and more.

“Of course people are angry. It’s a dangerous situation. What will you do when you have nothing and your neighbour has it all? You will jump the fence. Simple.”

Research has shown that income inequality is one of the strongest predictors of violence. The MRC says poverty and unemployment prevent men and women from getting access to “traditional sources of wellbeing, status and respect”.

“Inequality in access to wealth and opportunity results in feelings of low self-esteem, which are channelled into anger and frustration, and violence [including rape] is often used to gain the sought-after respect and power,” a policy document states.

Lekekela says: “Diepsloot’s troubles could easily spill over to places like Steyn City and Dainfern [another nearby wealthy golf estate]. People are bored and angry. There’s no recreation in Diepsloot. We need the rich people’s help and they need ours. We must work together otherwise we are all in a dilemma.”

Many children get buried here

At Diepsloot’s graveyard, Godfrey Mangoma’s black gumboots crush the dead leaves. He is walking over a charred field in faded blue overalls. It’s his job to organise the burials.

“It’s R622 for a grave for a small child and R1 237 for kids who are 10 years and older, the same price as for adults,” Mangoma says matter-of-factly. “We get many, many children – every week.”

Nearby are the graves that hold the remains of the Mali cousins in two tiny white coffins. Each girl’s tombstone is decorated with a pair of large etched angel wings.

Mangoma says: “I feel bad burying babies and children knowing that they have been murdered in very brutal ways, before they have had a chance to really live. I ask myself, why rape and kill children?”

He shuffles off again, speaking to himself. “There’s a good space there,” he says. “That’s the one that I will fill next.”

*Names have been changed to protect the identities of children. The police officer’s identity is being protected because he spoke to us without official permission. [Note this article was originally published on 2 October 2015]

You can make a difference

If you would like to help the Green Door, a project in Diepsloot that counsels victims of sexual and domestic violence, and helps them to access healthcare and report the crimes to the police, contact Brown Lekekela on 078 888 2144. The organisation needs clothes for women and children, sanitary pads, washing cloths, soap, toothbrushes, toothpaste, nonperishable food for children, a kettle, a microwave oven and a washing machine – and financial support.