The cast of Napo Masheane's latest play 'A New Song'.

History repeated itself recently when students from the #FeesMustFall protest movement marched to the Union Buildings in Pretoria to demand that the government freeze university fees for 2016 and to drive home their message that education should not be a privilege reserved only for the wealthy.

Forty-nine years ago, on August 9 1956, about 20 000 South African women of different races – the majority disenfranchised black African women – marched to the Union Buildings to protest against the hated pass laws imposed by the apartheid government.

This historical moment serves as a backdrop for poet and playwright Napo Masheane’s latest stage production, A New Song. It is fitting that it is being staged at a time when students are challenging the status quo and shaping their own future, just as their grandmothers did in 1956.

The play, which has an all-female cast, tells the story of a young “born-free”, Lindiwe, who feels powerless in the current political landscape. But her grandmother, Thokoza, encourages her to get involved in politics “to redefine the future and pick up a new song”.

The cast consists of Sibulele Gcilitshana, Thami Baleka, Jana Oosthuizen, Lichelelle Lerm, Pearl Noxolo Monama, Naledi Mabeleng, Vernicha Coetzee and Aneshree Paul.

A New Song moves between the 1950s, when Thokoza worked as a domestic worker, and 2015. Masheane uses music and dance to carry the audience from one time period to another. Masheane says no poetry features in the play because “the script is already poetic”.

“As much as the play is political and inspirational, it is also a play that entertains. The dance and music are something I feel add to the beauty of the words and narration of the storytelling,” she says.

Examples of the ordinary woman

The first part plays out in the 1950s in the posh suburb of Houghton in Johannesburg, where Thokoza and her friend Bantu, who is also a domestic worker, talk about joining the anti-pass law march.

Thokoza tries to rally as many domestic workers as she can to take part in the march.

“Bantu has been very faithful and loyal to her friends, but just a week before the actual march she decides not to go and stays with her madam,” says Masheane.

Bantu deceives her friend and gets a pass book. This moment in the play creates tension among the friends and reveals how people reacted in different ways to the pressures of apartheid and the struggle against it.

Masheane says she chose to tell the story through domestic workers because, to her, they are telling examples of the ordinary woman.

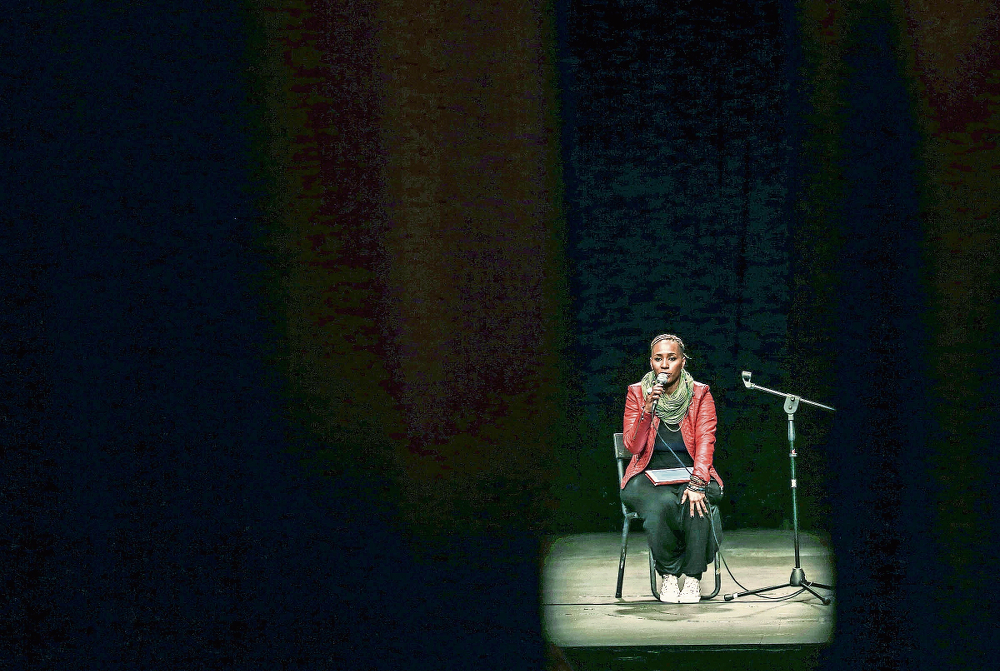

Napo Masheane (Nardus Engelbrecht/Gallo Images)

“They are women whose names never go down in history books; streets and monuments are never named after them. But these women, they take care of our children, they manage our homes, and they make sure that we are able to become the kind of people that we are in the world.

“So for me it’s about singing a song for them and saying: ‘I might not know your name, but I hear you and feel you. Your voice and story matter too.’”

Growing a culture of script-reading

Masheane’s grandmothers were both domestic workers. Their stories helped to inspire the script for A New Song, which was conceptualised in 2013 as part of a project at the Royal Court Theatre in London.

Masheane first presented A New Song as a play reading at the Royal Court in May 2014 (the venue was sold out) and staged another reading of the work at the Market Theatre earlier this year.

One of her works from the 2015 Children Monologues series – based on the testimonies of more than 200 South African children – was performed by Oscar-nominated actor Chiwetel Ejiofor at the Royal Court on October 25.

Play readings have not gained much attention in South Africa, Masheane says.

“I think in the 1990s a lot of white theatre practitioners did numerous play readings. But I think it’s a new thing for black theatre practitioners.

“I’m part of a collective of 11 South African playwrights, called the Playriot, who want to introduce the culture of script-reading to help create and develop audiences for our own work.”

The success of Masheane’s play readings prove that the theatre audience is ready for what she calls “a group of contemporary practitioners who connect the past and the present – who have a modern take on protest theatre”.

Playwrights such as Athol Fugard and Gibson Kente have given us classical stage productions that still stand above the rest, but over recent years we’ve seen citizens taking back their power, speaking out louder than before – giving protest theatre more material for the stage.

History in the making

In the second part of the play, Thokoza, now in her 60s, argues with Lindiwe about present-day South African politics.

“Why should I join politics?” Lindiwe asks her. The play indirectly attempts to answer this question, using the 1956 march as a point of departure and as a reminder of why South Africans commemorate Women’s Day on August 9.

Masheane has made great strides in South African theatre. A New Song is the first woman-directed, woman-produced play to be staged at the John Kani Theatre at the Market Theatre in Johannesburg.

“I fought throughout my life, in terms of theatre and trying to bring change to South African theatre, and to make sure that the voices of black women theatre practitioners are recognised and taken seriously,” says Masheane.

“So I feel like I’ve always been prepared for this time and that it’s the right time. It’s a huge honour and it humbles me. And yes, it puts pressure on my creativity, because whatever I put on stage will be part of South Africa’s theatre history.”