Mzwandile Buthelezi's work has graced album covers of jazz artists Thandi Ntuli's The Offering

Artist Mzwandile Buthelezi makes the diagonal trek from De Beer street across De Korte to get to number 81, The Orbit, where we’ve scheduled our lunchtime meeting. What would’ve been the spot to talk shop about his work is closed for the time being. So we recalibrate.

Over the past year or so, Buthelezi’s work has graced album covers of jazz artists Thandi Ntuli’s The Offering, Mandla Mlangeni’s Bhekisizwe, on which he did the layout and Benjamin Jephta’s Homecoming and others.

“My idea with ispan, njayam’ [work, my friend], is once I’ve done it and it’s out, it’s out. It’s up to the public to respond. I come from a grafitti background. You know graf man, you put up a piece [and] uyavaya, [then you go]” says Buthelezi, decked at a table at spot number two.

Photographer Muntu Vilakazi, whom we ran into and coerced into joining us, sits besides him. Buthelezi’s contribution to the above-mentioned albums, and to forthcoming work by jazz drummer Tumi Mogorosi, is great on its own. Vilakazi’s portrait of Mogorosi is the cover of the South African edition of his Project Elo LP.

Viewed in the context of South African jazz music, which is having a ‘what-a-time-to-be-alive’ moment right now, Buthelezi’s a one-man wolfpack carving a lane all of his own. He mentions bra Steve Mokwena of the Afrikan Freedom Station as another important link in his art-and-music exploits

“Being able to listen to abany’abantu [other people] in terms of criticism is important. But being able to self-critique is far better,” says Buthelezi.

“How I got into art is through itimer lam’[my dad], who was a jazz collector – he collected vinyl. Through growing up I got to interact with vinyl and songs. And through the album covers is how I started gaining interest in graphic design, but I didn’t love jazz at the time. Way later I got into hip hop, and through hip hop I started liking the samples, and then I started digging through the records. And that’s really how I started collecting,” says Buthelezi.

Art that compliments the music

Buthelezi got his first album art gig in 2007 through a friend. It was musician Vusi Mahlasela’s Guiding Star. A few years passed between that and him meeting pianist and composer Ntuli.

“We understood each other on a few levels. From [the work I did for] uThandi, cats started calling me,” he says.

“He’s just an incredible illustrator. I didn’t actually tell him what to do for the cover; I told him how I felt going through [the] recording process, and I asked him to interpret it in his own way,” said Ntuli in a chat we’d had earlier.

“In its own sense the artwork is its own creation. [It] complimented the music so well. I saw the first draft and was like ‘This is it!’ It was great to have him [be] part of the project,” she said.

“Going to the show,” a phrase Buthelezi returns to often throughout our conversation, is how the fine illustrating skills of graphic designer Sindiso Nyoni landed on The Brother Moves On’s recently-released Shiyanomayini EP.

Similarly, Nyoni represents a new wave of independent illustrators working with independent musicians in a manner that cuts through the red tape traditionally associated with record companies. He has produced various works for several independent imprints.

Nyoni’s philosophy’s to collaborate with as many people outside of his field of practice, hence the leap into music is an extension of himself, his vision.

“I’ve always believed that art can’t operate in isolation. I studied graphic design, but then I’ve found myself messing with performance artists. I’ve found myself messing with musicians and with fashion designers.”

Collaborative work

Nyoni believes that collaborative endeavours can only be beneficial.

“Everything inspires everything. You can’t say that the kind of work you’re doing has not been inspired by a poem some guy wrote, or by a building at the corner of Yeoville, or something like that,” he says.

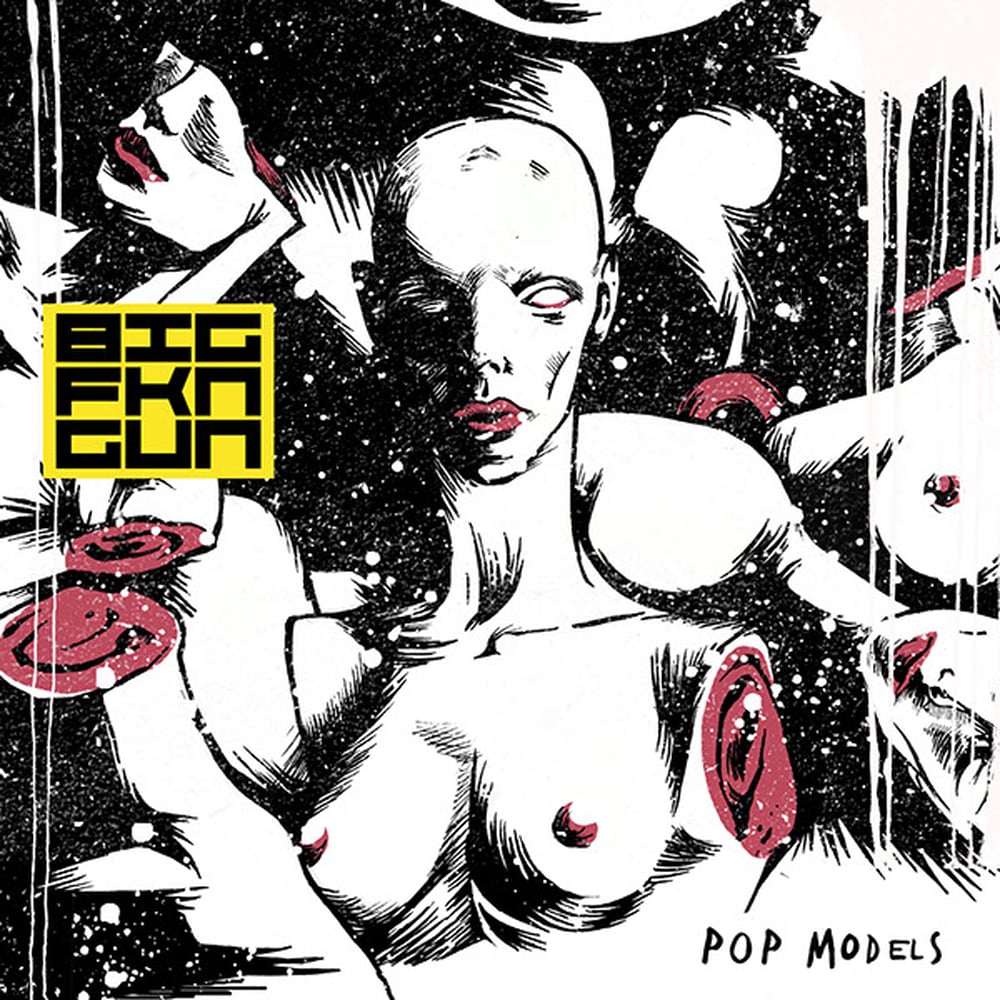

He also worked with BIG FKN GUN on their debut offering Pop Models. Pop Models is a packaging geek’s day in paradise. The front cover depicts a zombie character, eyes’ sclera filling the sockets and one side of the face stitched up. The matte paper onto which the CD sleeve is printed renders itself well to Nyoni’s polished-yet-raw aesthetic; running one’s hand over it has an effect similar to feeling on spray-painted surfaces.

BIG FKN GUN’s debut offering Pop Models.

The two-panel cover opens up to reveal more artwork in its inner nest: Six pieces which can be ordered any which way the owner desires are printed back-to-back, each illustrating the themes around which the 14-track EP – 12 song and 2 remixes – is centred.

“Sol (BFG’s front man) and I were a team back when I worked in advertising. He was my copywriter and I was his art director. I’d known about his band and sound all along so it was only a matter of time before I would lend my visual artistry to the sound of BFG. This wasn’t the first album cover I’ve done though,” he says via e-mail. Nyoni’s also contributed work to a few acts in Zimbabwe, and local acts in Jo’burg and Cape Town. He also did work on a number of albums released under the African Cream music label.

Buthelezi singles out artist Hargreaves Ntukwana (Dollar Brand’s Underground In Africa, David Hewitt’s The Storyteller, and others) as a big inspiration to his approach to art. He also speaks about history’s tendency to single out one person out of an entire movement and elevate them to messianic status at the expense of those who formed and informed ideologies that guided the movement.

In this case it’s the work of another artist, Dumile Feni. Buthelezi does acknowledge Feni – he is a fan of that whole Polly Street art scene, including Hargreaves, Ezrom Legae, Fikile Magadlela and others – but is cautions against the white-washing of a paralysing white gaze in need of a hero to designate. This gaze, which allows Feni’s ‘Goya of the Townships’ nickname to be used unquestioningly, also invents terms such as ‘township art’ to continue the legacy of blackness as being lesser-than.

“There was a style and culture that developed in terms of art and drawing ekasi based on [township art]. Growing up eNdofaya, there were a few people that had Hargreaves Ntukwana and Fikile Magadlela piece in their houses. So it’s not necessarily [Dumile’s influence] alone (although this has been huge), but things I’ve seen ekasi while growing up.”

The working process

Buthelezi explains his working process. “I spend a lot of time drawing with music in the background; I kind of improvise with music,” he says. “Music is a universal language, music can also put you in a trance and if you listen carefully…in that space, you can have other channels opened. Music exists in an empty space,” he says.

“If you look at a guitar, for example, the sound doesn’t come from the strumming of the string – it comes from the hollow space. Same with the drum as well; it’s not the skin that’s making the sound, it’s the hollow space. We can all enjoy music even without vocals; we all feel wind yet we can’t see it. What I try to do most of the time is to pull out the soul of the music. I try to draw what I’m feeling.

“I could be reading a poem, and I start drawing starting with a circle most of the time. Most of the drawings have got circles. That comes from the circle of life, the empty space.”