‘Translation is not a matter of words only: it is a matter of making intelligible a whole culture,” British writer Anthony Burgess wrote.

That encapsulates the experience of Sahel Sounds’ Christopher Kirkley and Tuareg guitarist Mdou Moctar, who this year launched their adaptation of Prince’s 1984 rock musical Purple Rain, transferring it to West Africa, to the windswept streets of Agadez in Niger, to be specific.

Sure, their Purple Rain has many familiar scenes of guitar-shredding, purple motorbikes and family conflict, but the narrative had to adapt to a Tuareg context.

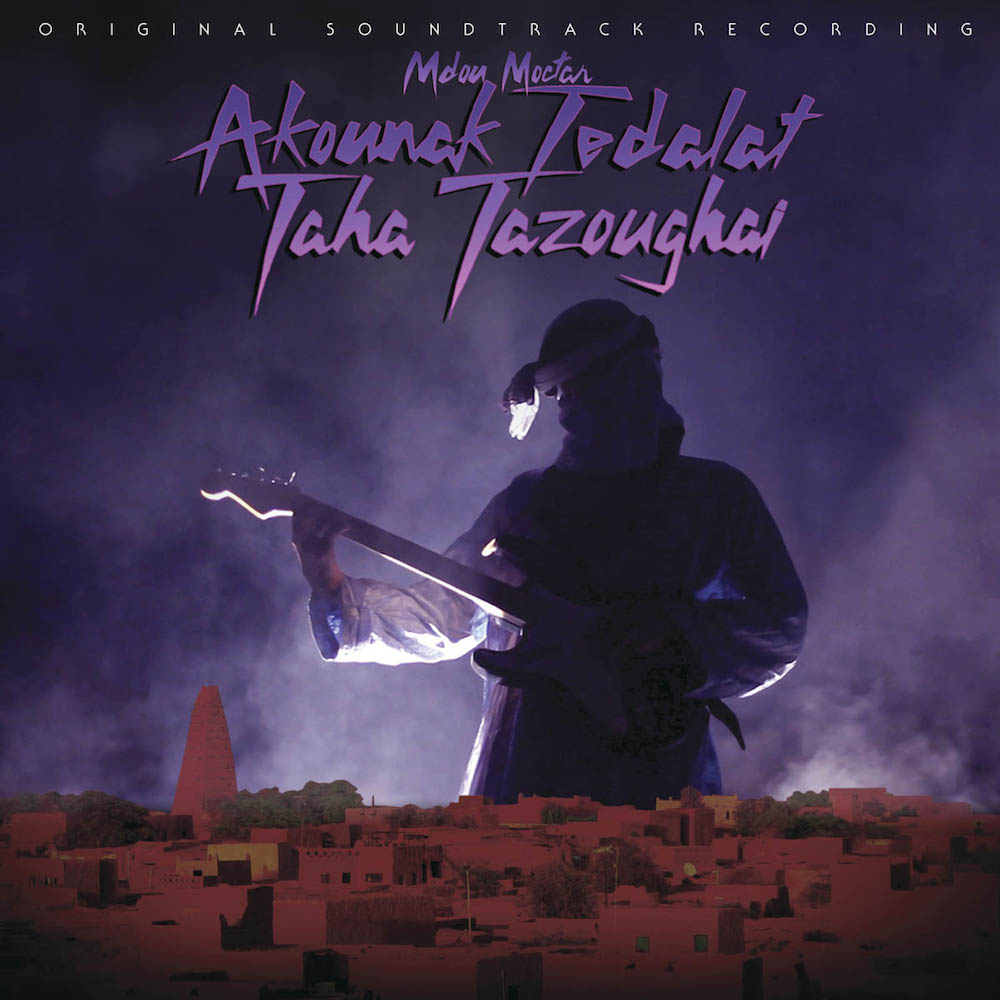

First, it would have to be in the Tuareg language Tamashek. But Tamashek has no word for “purple”. “My language doesn’t have a word for every colour,” says Moctar. The film now bears the name Akounak Tedalat Taha Tazoughai — “Rain the Colour of Blue with a little Red in it”.

Kirkley moved to West Africa after graduating from Oregon State, where he’d studied biology. Inspired by ethnomusicologists such as Alan Lomax, he wanted to “record something important”. “I feel that the American folk tradition is indebted to the work of recorders and archivists,” says Kirkley. “I wanted to do something of the same in the Sahara.”

So he travelled from town to town with a guitar, jamming with local musicians as he went, swapping music via mobile phones and memory cards. “MP3 trading is a pretty common social activity,” he says. “Browsing phones and collections ?of friends and choosing the songs you like.”

If Kirkley heard songs that spoke to him, he tried to track down the musicians who had made them. In 2009 he started a blog, Sahel Sounds, to distribute songs he’d discovered, as well as his recordings, and the blog later became a record label.

“In much of West Africa, cellphones are used as all-purpose multimedia devices,” he says. “In lieu of personal computers and high-speed internet, knock-off cellphones house portable music collections, playback songs on tinny built-in speakers, and can swap files in a very literal peer-to-peer Bluetooth wireless transfer.”

This unofficial MP3 network trades songs from Abidjan to Bamako and Algiers. “I’ve dropped off music in Niger and found that same song in Mauritania,” Kirkley told Rolling Stone. “It had made its way 1?000km.”

In December 2011 Kirkley released his first compilation, Music from Saharan Cellphones. It featured Moctar’s track Tahoultine — the song that announced Moctar to the world beyond West Africa.

Moctar’s glorious tune was also the opening track of an autotune-heavy album of innovative new Tuareg music. Inspired by recordings for Hausa films coming out of northern Nigeria, Moctar decamped to Ahmadia Multimedia Sound Studio in Sokoto in 2008.

Combining a Bollywood influence with local rhythms, the Hausa musicians use autotuned robotic vocals floating on drum machine patterns as the synths play the melodies.

“I really like the sound of this electronic music,” Moctar says. “I wondered what traditional Tuareg music would sound like when combined with electronic music, and so I decided to try.”

Ana, the album that came out of his Nigeria trip, didn’t see commercial release until September 2014, when Sahel Sounds put it out. In the meantime one of its songs, Anar, an autotuned love ballad, was a smash hit on the Sahara cellphone network. (Moctar’s songs generally take the form of tales of anguished love and broken hearts.)

When Kirkley met Moctar, he saw a maverick, a pioneer, pushing the boundaries of Taureg music. They became good friends.

Sometime in the next few years, the idea of remaking Purple Rain with Moctar came up. Kirkley had spotted the similarities between Moctar’s story and Prince’s in Purple Rain. Moctar was born in the town of Abalak, in the Azawagh desert of Niger. He taught himself the guitar on a homemade instrument even though his family wanted him to have nothing to do with music.

In 2002 he moved to Libya in search of work to support his family. He worked there for three years. “When I moved to Lybia I stopped playing music,” he says. But he did ?go to a gig by his fellow Nigerese Tuareg guitarist and singer Hadani Alhousseini, a former member of Etran Finatawa.

That moment changed everything for Moctar. He decided to chart a course back to music.

The soundtrack to Akounak Teledat Taha Tazoughai is the first studio album recorded by Mdou Moctar and his band. (Supplied)

Moctar says he had never seen Purple Rain before they began planning to make their film. After a successful crowd-funding campaign, they began shooting. “Over three weeks in Niger, we found a cast and crew, and most importantly, began rewriting the story from the perspective and experiences of Mdou and his fellow musicians,” says Kirkley.

“The story was intended as a ?collaboration. Everything was subject to constant revision, with input ?from cast and crew,” says Kirkley. “Sets, designs, clothing, actors, and even the story itself, were rewritten during production.”

Prince’s father in Purple Rain was a violent, wife-beating, alcoholic man. Moctar’s father has been transformed into a pious Muslim, who forbids his son to play music and even burns his son’s guitar in one scene.

Kirkley says that although he wanted to make the film representative of how he saw Agadez this view came into conflict with his cast and crew as they worked on the film.

“When a sight was deemed unsightly, we covered it up,” says ?Kirkley. “The day-to-day realities — the corner dusty boutique, the donkeys milling about dirt streets, the blown-out amplifiers and bricolage guitars — were not considered the cinematic ideal.

“Often, locations did not correspond to my vision,” he says. “When a house was deemed too small, we moved to a bigger one.”

He says the lead actress demanded that she wear fine clothes when she was shooting scenes, so her character had to be rewritten as very rich, with expensive habits.

Moctar sees things slightly differently. He sees the finished film as a story about the daily struggle in Niger. “Most of the things in the movie are real,” he says.

Before its premieres in the United States (at the Hollywood Theatre in Portland, Oregon) and Franc (Le Gyptis in Marseilles), the film was screened in Agadez. It was September 2014.

“It was a very vocal crowd, filled over capacity, and the film was punctuated with cheers and applause,” says Kirkley. He is releasing the film in West Africa on DVD, USB or via cellphones.

The Akounak Tedalat Taha Tazoughai soundtrack album is the first studio album Moctar has recorded with his band. Mesmerising cyclical guitar riffs dominate the album, propelled by raw bass and percussion — a rhythm section that switches between drawing its juice from the rich wells of roots reggae and that of traditional Tuareg percussion.

Whether noodling or full-out shredding, Moctar is a formidable guitarist and the soundtrack has him on full display.

Kirkley says the album features recordings made over the past ?two years, some as “on the fly, spontaneous sessions during pre-production”, and others during the shoots. Yet some were recorded in a studio ?in Marseille.

“Some of the instrumental music is a result of running out of gas in the bush and toying around with a portable amplifier under a tree 20km outside of Agadez,” he laughs.

Meanwhile, Moctar has become a global touring artist. He has completed several European tours overthe past two years, as well as in Turkey and Canada. The film has screened in France, Spain, Portugal and Switzerland.

“It is surreal,” says Moctar, clearly grappling for words. “I never even dreamed about being able to do tours with my music,” he says. “I enjoy playing for audiences. It is what makes me tick,” he says.

“When I compose, I want to see the audience’s reaction.” Tuareg music has come a long way since Tinariwen burst on to the international scene in the early 2000s. Fourteen years later, a new generation of Tuareg guitarists — of whom Moctar is a prime example — are taking the music boldly forward into a new future. It’s a purple dawn for Tuareg youth, a new Tamashek poetry for a new power generation.

Read more from Lloyd Gedye or follow him here