SKA and MeerKAT

This year, white dishes will mushroom on the Northern Cape’s dusty plains as South Africa’s 64-dish MeerKAT starts to take shape. The MeerKAT is a South African-designed and built radio telescope, a precursor to showcase the country’s radio telescope engineering ability.

However, even though there are fewer than a handful of antennae on the site now, astronomers around the world have already booked five years’ observation on MeerKAT.

This R2-billion telescope will be the largest radio telescope of its kind in the southern hemisphere until it forms part of the larger Square Kilometre Array (SKA) at the end of the decade. This thousand-dish leviathan will then usurp the title. Africa and Australia will host the SKA, but its core will be near the small Karoo town of Carnarvon.

The SKA will be the largest radio telescope in the world; in fact, once it is complete, it will be the largest scientific instrument on the planet. But the problem with large scientific projects is that it takes a while to see the fruit of the behind-the-scenes labour of hundreds of scientists, engineers, bureaucrats and diplomats.

In 2016, we will see more tangible proof of their efforts, as the MeerKAT antennae proliferate. Although MeerKAT’s completion date has been set for the beginning of next year, we’re likely to see some results coming out of the telescope as more antennae are added.

Lee Berger

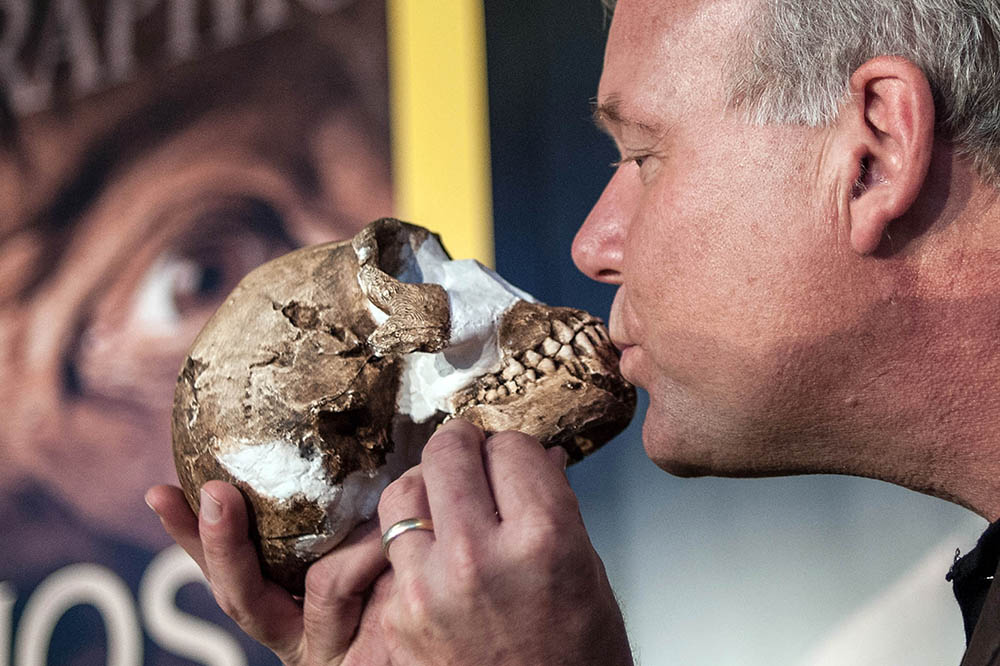

Palaeoscientist Lee Berger wowed the world in 2015, when he unveiled possible human ancestor Homo naledi and a treasure trove of skeletons in the Dinaledi Cave, in the Cradle of Humankind in Gauteng. Berger, a professor at the University of the Witwatersrand and National Geographic explorer-in-residence, was also responsible for the discovery of Australopithecus sediba in 2008 – another hominin.

While there has been controversy about the Homo naledi find – from the scientific community, with question marks over the researchers’ conclusions, and from South African society at large, where the announcement sparked a race row – there is no doubt Berger has remarkable talent. He makes finding hominin fossils, some of the most rare and precious artefacts on Earth, look easy.

Before the Homo naledi announcement, Berger told the Mail & Guardian: “We’re a species with backyard syndrome: we think we know our own backyard, but we just look past it.”

He says there are now teams of explorers combing through the green, rolling plains of the Cradle of Humankind, looking for fossils.

“We’re in for one of the greatest periods of discovery in this field, and that’s going to be exciting,” he said. So while there is nothing officially on the scientific cards for palaeoscience this year, keep an eye on Berger: who knows what he will find next?

Palaeoscientist Lee Berger with a replica of a Homo naledi skull. The hominin is a possible human ancestor. (Stefan Heunis, AFP)

Gene editing

Gene editing is an area of science to be watched on two fronts: the technological leaps that appear to be happening every other day, and the legislation and oversight that is lagging relatively far behind. Gene editing involves removing, adding or manipulating parts of DNA, and scientists are finding new and cheaper ways to do this – on plants, animals and perhaps one day on humans. This has life-saving implications for people suffering from genetic disorders. In a paper published in the prestigious journal Science on December 31 last year, researchers showed that they had edited mutations in the dystrophin gene from mice. Flaws in this gene are responsible for Duchenne muscular dystrophy in humans, a disease which affects about one in 4 000 young boys, whose life expectancy seldom exceeds 25 years.

A Chinese team last year disclosed – to an international outcry – that they had attempted gene editing on human embryos, but found that the tools were not accurate enough to achieve the editing required. However, the tools being used to do this sort of editing are becoming more sophisticated. So, expect many new revelations in this exciting field. But at the same time, 2016 will be the year to watch how states control it – because it is a powerful technology, and all powerful technologies need to be regulated.

Gene editing has life-saving implications for those with genetic disorders. (Madelene Cronje, M&G)

Large Hadron Collider

In an underground tunnel, scientists are smashing particles together at incredibly high energies to understand the smallest constituents of the universe. In 2015, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) – a 27km particle accelerator that straddles the border between France and Switzerland and is about 100m underground – managed to increase the energies at which the atoms collide by more than 50%, creating a new record for the highest energy particle collisions.

By sifting through the detritus of these collisions, researchers are able to identify and detect new particles. While the Higgs boson, otherwise known as the God particle, is the most famous discovery of the LHC, almost entirely due to its catchy name, scientists have discovered a number of new particles, filling very tiny holes in our standard model of the universe. This model describes how matter and forces interact.

Last month, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (Cern), which operates the LHC, announced the possibility of a new boson and this resulted in a flurry of 150 academic papers on online preprint archive arXiv. With the higher collision energies (13 TeV), we are very likely going to see a glut of discoveries coming from the scientists at Cern, which also include South Africans. But the popularity of new particles will almost certainly depend on what they are named.

High-energy particle collisions in the Large Hadron Collider will lead to a glut of discoveries.

Mars

Now that there is the promise of liquid water on Mars, it will take more than a 225-million km gulf to keep humans away from the red planet. We knew that there had once been ancient water and that there are present-day polar ice caps, but the briny water Nasa announced last year changes everything.

Liquid water is necessary for life as we know it, adding to evidence that the planet could support life. With this increased attention, not to mention Nasa’s rovers on the planet, we are certain to find out more about the planet that is increasingly being viewed as humanity’s Plan B – in case we destroy our current home.

And while we are making great strides in understanding the science of Mars, the technology to get us there is also stepping up to the plate. Late last year, South Africa-born Elon Musk’s SpaceX managed to launch and land the same rocket back on the launcher, an historic feat that will change space exploration because, to date, we weren’t able to reuse rockets. Being able to do so will slash the costs of space travel: you don’t need a new rocket each time you want to launch, and you would not have to carry another rocket to, say, Mars, if you wanted to return.

However, there are some people who don’t want to return to Earth. This year, Dutch not-for-profit organisation Mars One will begin training its final 100 candidates, including five South Africans, who want a one-way ticket to Mars. From science to exploration, Mars is the planet to watch in 2016.

Mars will make headlines this year as scientists learn more about the planet.