Arnhem Mirror from Johan van der Schijff's I to I.

It took more than a hashtag campaign to remove the Cecil Rhodes statue from its prime position on the University of Cape Town campus. It took a large crane and a team of men to extricate it from its prime position, making clear it had never been designed with removal in mind.

This was no doubt part of the misplaced hubris underlying its creation. When it was eventually detached from its plinth even the notion of its permanence was only partially shattered – it wasn’t destroyed – just relocated. Nevertheless, this landmark moment, dislodged other seemingly enduring conditions; such as the slow and ineffective transformation of our centres of education, and our society at large. Public art, monuments also came under scrutiny; however, the fate of existing ones was the focus rather than a complete overhaul of the role and design of public monuments.

This was an oversight and a conundrum that has recently been addressed by an unlikely individual – a Pretoria-born Afrikaner who spent time at veldschool – or as Johann van der Schijff puts it “our version of Hitler’s youth camps.” He seems to have been a skeptical non-conformist since those days when he scoffed at measuring his pulse while listening to Neil Diamond’s music to gauge the negative effects of rock music. As a lecturer at UCT, who teaches sculpture, he is perhaps well placed to suggest alternative public art models.

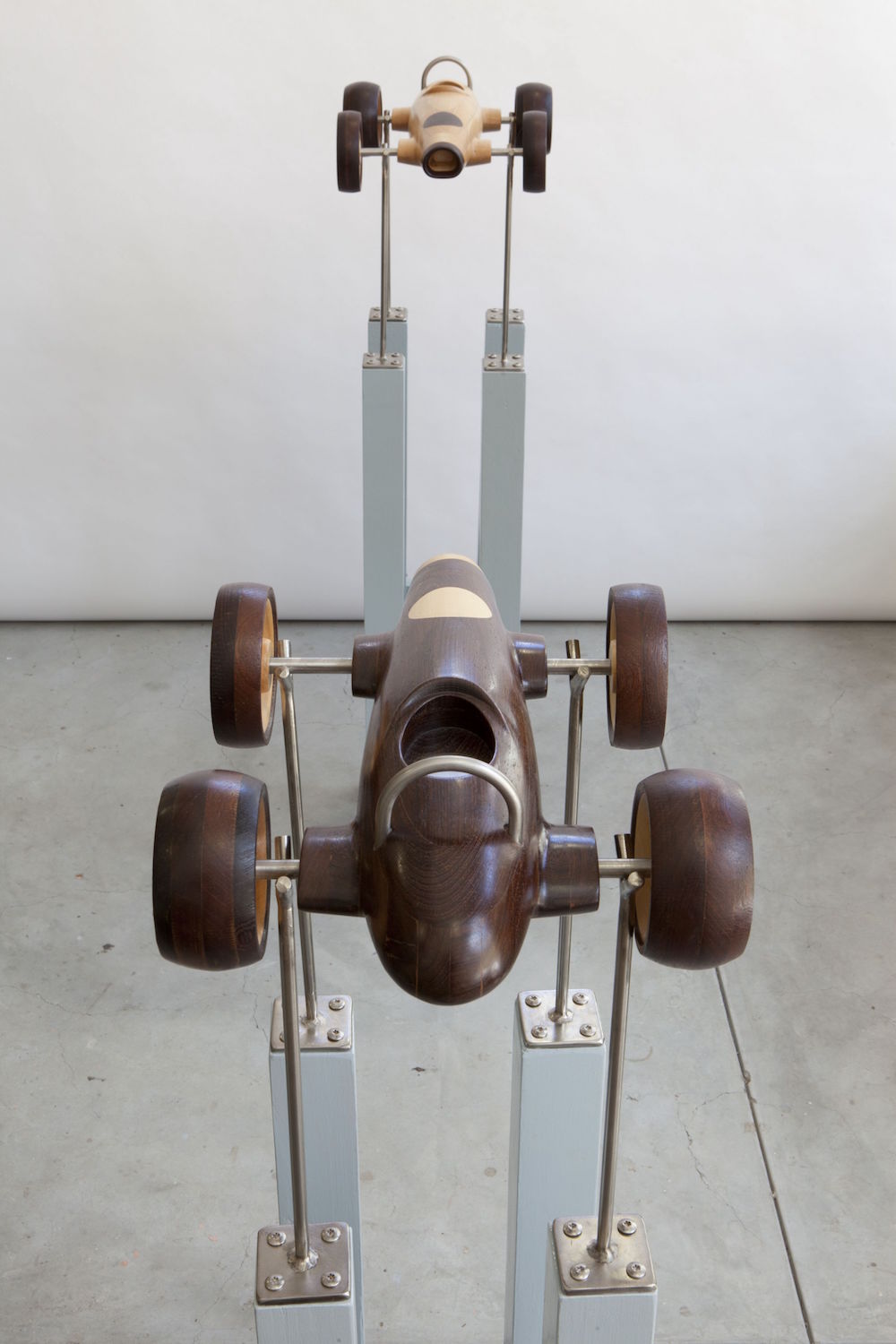

He proposes some interesting ones in his recent exhibition, I to I, showing at the Art on Paper Gallery in Joburg, where via a collection of models for public sculptures he completely overturns the design and function of them. He advances two radical alterations to public art; firstly, that monuments should never be conceived of as being impermanent from the get-go. To this end all of his public artworks have wheels attached to them so that not only can they be removed quickly, but, potentially, if they prove useful to society, can travel to different sites at different times where they can be accessed (or rejected) by different communities.

The second radical idea he advances through this show is that monuments should be functional in that they set the stage for public performances and can be used by the public rather than just operate as objects to gaze upon. For this reason he has designed a feet-washing podium and one based on a Roman Catholic confessional booth – there are two seats on either side of divide with a grill through which the two participants can communicate to each other without revealing their identity.

Chicken run (Johan van Der Schijff)

Both of these podiums are rendered in minature and 1/3 scale, however, he would have liked them to be realised and has sent the proposals to various public art committees and such. He felt that gestures of repentance shouldn’t be done behind closed doors but should be publicly enacted, as in the manner of the TRC. The foot-washing podium was made in response to Adrian Vlok’s eagerness to clean the feet of his victims or their relatives.

Van der Schijff conceived of these podiums and the notion of temporary public sculptures in 2007 – long before the #rhodesmustfall campaign. He encountered Vlok during the height of apartheid as a student at the University of Pretoria, where along with other arts students he was protesting against the government’s policies.

“I remember he got into his car and he opened his electric window and he laughed at us. He was frightening,” recalls Van der Schijff.

It is probably for this reason that he was completely skeptical of Vlok’s attempt at repentance via foot washing.

“Is he doing it because he is Christian and is afraid of how God will judge him or because he is genuinely repentant?” asks Van der Schijff.

I to I (Johann van der Schijff)

This level of skepticism underlies his foot-washing podium and also the confessional one, which appears like a prison or military device – its design was inspired by the look of Kaspirs and Ratels from the apartheid era.

“It is absurd, why would you want to talk to someone through this thing,” he says moving the grill back and forth.

It should be surprising that he is cynical about his own creations but this is an intrinsic part of them; for while they present an opportunity for South Africans to come to terms with the past individually and publicly, he is unsure whether can be done or have any impact. This view is based on his perceived failure of the TRC.

This may explain why these podiums have never been executed in reality but also why the rest of his exhibition is largely devoted to the artist analysing his own middle-class white existence. In this way his exhibition is a bit like one of his podiums; a temporary public show of coming to terms with his position in society. He makes a tongue-in-cheek ‘confession’ to eating a Woolies sandwich for lunch via a wood sculpture that mirrors the plastic packaging it comes in. In this way he monumentalises his privilege – makes his ‘shame’ concrete. Does he really confront his privilege by doing so, can one? These are the questions that beat at the heart of this exhibition.

Art should pose questions not answers and perhaps that ultimately should drive the creation of our new public monuments. Not only should they be temporary and functional, as Van der Schijff proposes, but their value should always be conditional, before they are wheeled away and hidden from public view.

Independently generated by IncorrigibleCorrigall and subsidised by the gallery.

‘I to I’ is showing at the Art on Paper Gallery in Joburg until 30 January 2016.