In the winter of 2014 I accompanied a man who was in search of a Cecil John Rhodes statue that had been removed from an old train station in his hometown of Mahikeng in the North West.

We drove for more than four hours, from Mahikeng to Kimberley, to fulfil his aim of confronting the men he believed had stolen public property and moved it to the Kimberley Club, their elitist enclave, away from public view.

Thinking now about the interaction between heritage activist and farmer Galefele Molema and then Kimberley Club secretary Randall Bruce, I realise that Molema’s quest was probably more symbolic than physical. Perhaps this was a cathartic journey of reassessing his notions of collective history.

Perhaps he knew, somewhere in his mind, that the Rhodes statue would never be returned to Mahikeng, where it had marked a pivotal stop in Rhodes’s ill-fated cross-continental rail project. Postcolonial bureaucratic intransigence had found perfect bedfellows in Rhodes cultists hellbent on safeguarding a piece of imperialistic nostalgia.

The North West Provincial Heritage Resources Authority displayed no sudden urge to facilitate the return of the statue, this time to a refurbished museum in Mahikeng, as Molema wished. And as for the Kimberley Club and their newly acquired property, they wore the self-satisfied look of impunity and the smugness of reunited kinsmen.

Driving back to Mahikeng with Molema, I wondered whether he would appreciate anew the bloodied bonds that tie the colonisers and their descendants to those who must inherit their edifices.

The colonised, despite being a numerical majority, remain, to all intents and purposes, a cultural minority, ensnared by monuments to their conquest.

Meleko Mokgosi’s solo exhibition Comrades is so powerful that in a matter of a few panels of paintings and ancillary text, it brings into sharp focus all the violence of capture and the muted horror of the past 22 years of “flag freedom”.

Currently showing at Cape Town’s Stevenson gallery, Comrades forms the second chapter of the artist’s Democratic Intuition project. This in turn comes on the heels of his eight-chapter installation project Pax Kaffraria, in which Mokgosi looked at postcolonial aesthetics alongside issues of national identification, globalisation, trans-nationality and whiteness.

The series title is apparently a reference to United States academic and theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, who, according to a note on the website of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston in the US, “suggests that to recognise the ability of other individuals and their children to think abstractly and take part in civic life is inherently democratic. Mokgosi is interested in the pursuit of recognition as both a primary goal of suppressed peoples and the essence of artistic expression.”

Mokgosi’s oeuvre is carefully considered work that respects form, only to subvert it. Like Pax Kaffraria, Comrades is nostalgic, if only in a discomforting way.

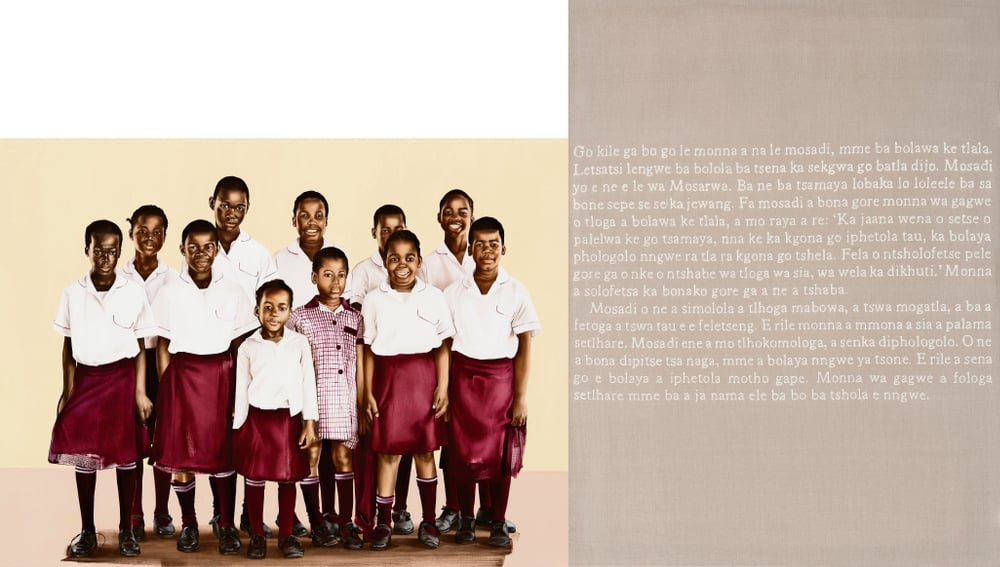

The Botswana-born, US-based artist’s use of history painting to depict subjects in unaffected poses forces us to look at histories taken for granted. His series of panels depicting schoolchildren, for example, comprises eloquent interrogations into both the continued neglect of education and the ruse of the concerted, quiet violence of assimilation.

It is no accident that in Mokgosi’s depiction of students in multiracial schools, the black children are not only outnumbered but by implication are slightly shielded from prominence.

His Comrades II panel depicts three smiling matriculants of a model C high school. They stand in an inverted triangle, with the head boy flanked by his two deputies. The fact that the black student is in the minority in this painting, as is the one depicted in Comrades IV, harks back to a time when black students were first allowed into government-subsidised white schools.

By depicting them as minorities, Mokgosi seems to acknowledge the assimilation into whiteness they had to endure and ponders the pitfalls of imagined exceptionalism they may stumble into later in life. The artist, born in 1981, may have a personal recollection of the epoch.

The panels in Comrades II and Comrades IV may be viewed as complementary to the images of schoolchildren attending black schools depicted in Comrades I and Comrades III.

Mokgosi’s almost photographic painterly precision means that “fiction” is starker than fact when it comes to pondering the contrasts between these two groups.

Comrades I

The lack of uniformity of the schoolgirls’ uniforms in Comrades I, the state of their shoes and their varied facial expressions speak of the precariousness of black life. The image evokes a sense of foreboding for their future.

Their high school counterparts, clad in an assortment of pullovers, plain blazers and rolled-up sleeves (Comrades III), brim with pre-adulthood swagger. These are the same smiles that will be cut short as they fail to complete their degrees, hamstrung by financial woes and the alienating environment of tertiary institutions that deny their intellect and humanity.

But although Mokgosi acknowledges the structural pitfalls and their dehumanising impetus, his subjects have an indelible humanity. His painting technique and use of colour, for example, go a long way towards rehabilitating the portrayal of black figures in popular discourse, returning to them a dignified individuality.

If the panels of folkloric text accompanying the paintings are taken into consideration, one is forced to reckon that patriarchy is no less an evil than the systematic beast of racism.

It is especially poignant in the wake of the current controversy over the “maidens’ bursary”, which provides funding for young women in KwaZulu-Natal’s uThukela municipality as long as they undergo regular virginity testing.

More so than the paintings, these text panels force us to consider a completely new Africa that can jump “black into the future”, as it were, thereby circumventing the perpetual stasis depicted in the three panels that make up Comrades V.

By refusing to translate them, Mokgosi dons a futurist’s hat, transmitting secret technology from the confines of a gallery.

Explaining the role of the texts, Mokgosi says: “In my reasoning, they are paintings since the written texts were done by carefully painting into the portrait linen with bleach, then neutralising the surface so that the bleach does not continue to react with the fabric. So instead of adding pigment, I am removing it from the actual support that usually houses painted images. And the fabric is also specific because linen has very different academic and connotative qualities to cotton-duck canvas.”

Mokgosi says he wanted to use the texts as a way of providing already existing tools that “some might say are not Eurocentric, that can allow us to think about various things from capitalism to power to greed and an engagement with the ethical”.

With this instalment in the saga of Democratic Intuition, Mokgosi is beguilingly instructive and interventionist – not only asking the questions but suggesting that the answers were with us all along.

Comrades is on at Stevenson in Woodstock, Cape Town, until February 27. Visit stevenson.info

A brief Q & A with Meleko Mokgosi

There is something uncanny to the timing of your work, the decision to exhibit it in Southern Africa at this moment. This is your first exhibition on this part of the continent in over a decade. Was it a deliberate decision to hold your tongue, as it were, until now?

Unfortunately ,I do not have much say in exhibition opportunities, so it is not a matter of a wilful absence but more about the desire from spaces to want to show my work. Fortunately, I have been working with the Stevenson gallery for some time and they are an absolutely incredible in their support and framing of what I do.

I am curious as to your process in painting faces. I read somewhere that when you go to Botswana, your family members keep a stack of newspaper clippings and other materials at your ready. How much of this material feeds into the some of the emphathetically portrayed faces. Are you using photographic source material for these?

— Yes, I only use materials from multiple sources, including newspapers, magazines, periodicals, as well photographs I take. During every trip to Botswana and South Africa, I make sure to do as much traveling as possible and do a fair amount of photography.

The images of so called Model C school uniforms invoke the quiet violence of assimilation that many South Africans have had to endure, starting, in some cases, in the early Nineties. How much of your personal experience feeds into the work?

Although my work is not autobiographical, it does bare traces of my experiences. This has always been very important to me, both as an artist and also looking at other people’s artwork.

When looking at or making artwork, I believe it is always more important to be able to see or connect to the producer’s investment in the material. The reason I say this is because there are times when artists seem to want to make objects from what they think is a neutral positionality, and therefore think that what they want to communicate can speak to everyone at once.

Obviously I have problems with this because therein lies a universalising impulse that we must always work against. Sure there might be a desire to speak across divides and reach everyone, but we can only speak in one tongue to select group of individuals. All this to say that there needs to be a constant and careful analysis of our positionality in narrative structures within which we are implicated directly and indirectly. So I can only make what I make from my positionality and only with reference to my experiences as person.

While there has been a lot of calls for removals of monuments in South Africa, there has also been a lot of reclaiming of these monuments by Afrikaans cultural groups and separatists, particularly in places like Orania. Do you think the fact that the glut of post-apartheid monuments amount to Nelson Mandela statues says something of our disconnect as to how we memorialise ourselves as Africans?

Regarding the relationship between Comrades and the anti-colonial statue movement: My work and practice have always been preoccupied by the tensions and histories that the the anti-colonial statue movement raises: that is the telling of one’s histories versus official History.

What is most interesting about this movement is how it illustrates the process of defining oneself as a postcolonial nation. Something with which my work is interested in coming to terms is both how the postcolonial must negotiate itself away from the colonial (and therefore recognize the influence and force of the colonial moment), as well as debunking any attachment to an idea of a problem-free postcolonial state. For me, this myth does similar damage as that of the “noble savage,” succeeding in flattening and ignoring the complexities of human history and differences.

Also, what comes to mind is the role of the students in this movement. Throughout history and around the world, students have been the engine for change [for example, in Sharpeville], which shows the utopian tendencies and possibilities of the process of learning in a democratic environment. But tethered to this, something I have long been trying to explore in my work is the instrumentalisation of education to produce certain kinds of citizens.

Education was and has been one of the most powerful tools to transfer and instil the dominant class’s ideological beliefs. So, how is this site both an engine for change, where the youth collectively dare to think toward a more inclusive future while at the same time one of the institutions most responsible for exclusion and the repression of voices.

Finally, perhaps something my practice of painting can capture is the epistemic violence of representation. That in any representation, be it a drawing or political representation, some violence, covering over, or distortion necessarily happens. This might be a way of thinking about the tensions behind the education system as place of change and stagnation. In any case, these are the conditions that surround the democratic postcolonial state, which I have been interested in pointing in particularly in the context and history of southern Africa.

So far, how do you see the chapters of Democratic Intuition unfolding? To you, how is Democratic Intuition a logical progression from Pax Kaffraria? Where can one see the first chapter of Democratic Intuition?

The first chapter of Democratic Intuition was exhibited last year at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston. I believe that chapter is in storage in Los Angeles, yet I am in the process of updating my website to include images from that installation. Whereas Pax Kaffraria examined national identification, anti-colonial sentiments and post-colonial histories, Democratic Intuition aims to ask questions about how one can approach ideas of the democratic in relation to the daily-lived experiences of the subjects that occupy southern Africa.

So Pax Kaffaria focused on larger ideas around the nation-state and nationalism, and in Democratic Intuition, I hope to have a more intimate focus on particular issues within the nation-state and trying to build more specificity into the images I am creating.

How significant are the locations where each chapter is exhibited?

All the installations try to pay careful attention to the space that it is exhibited in. Although they are not site specific, I would work very closely with the dimensions of the space to create work that suit it in terms of scale and content. So the location is a very important working through during the process of making the work.

Read more from Kwanele Sosibo or follow him on Twitter