The demise of apartheid freed Zakes Mda to explore the historical novel.

It is absorbing to hear author Zakes Mda speak of his psychological relationship with South Africa. In his unwieldy memoir, Sometimes There Is a Void, he writes of his tenure in the United States as migrant labour.

Publicly, and in conversation, he often characterise his place in South African society as that of an “outsider” in relation to the “inner circle of people who are eating”. There is a humorous emphasis that the Ohio University-based professor places on the verb, one that is in keeping with his long-running critique of our country’s descent into avarice.

It has appeared in his novels in various ways (take 2009’s Black Diamonds, for instance) as well as in newsprint and, of late, his Twitter timeline.

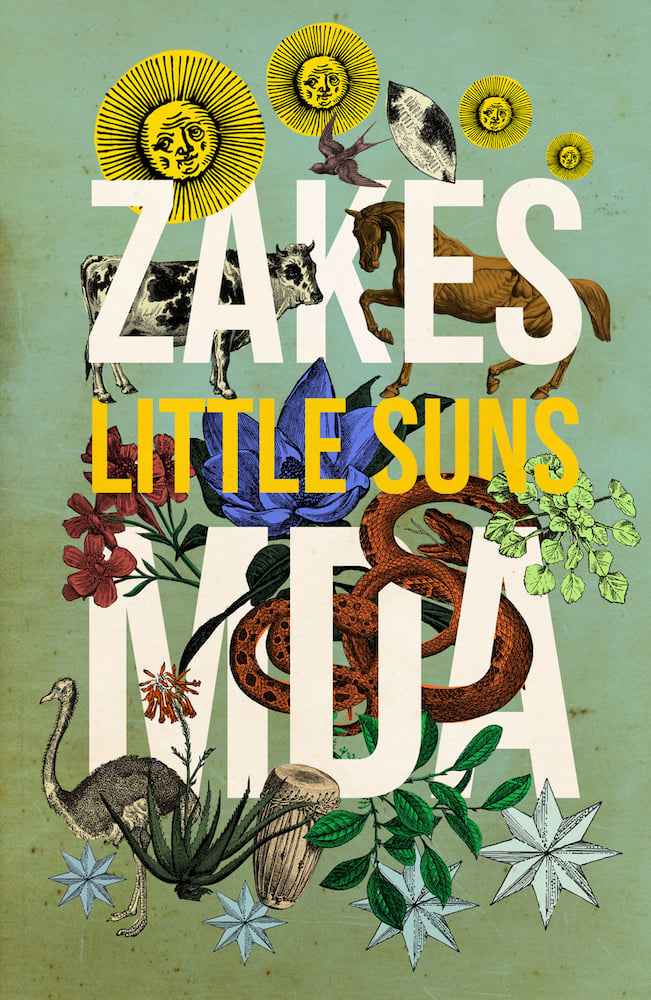

In fact, it is to Twitter that Mda turns to augment a response to a question about whether his ultimately metaphysical distance from South Africa has influenced his predilection for the historical novel. He scrolls up a December discussion with an advocate, Maru Moremogolo, who asserts that Mda’s latest novel, Little Suns, “brings context to judicial powers of traditional leaders, perfect timing [abaThembu king] #Dalindyebo”.

Moremogolo explains that, in Little Suns, the 19th-century King Mhlontlo of the amaMpondomise wanted his judicial powers restored by magistrate Hamilton Hope – and late last year Dalindyebo’s defence for his own crimes is that they were committed while he was carrying out “judicial” functions.

Mda found the comparison affirming to his practice. “When you read my historical novels, take The Sculptors of Mapungubwe, for instance, you’re actually reading about the present,” he says as we sit around an outdoor table at the Johannesburg guest house he is staying in. “The issues that we grapple with are the same issues that they are grappling with today. A historical novel that is not about the issues of today is useless.”

It is on the page, as opposed to on the stage as a panellist, that Mda offers us an opportunity for time travel and introspection.

Little Suns tells the story of the displacement of the amaMpondomise after Mhlontlo’s decision to kill Hope. The magistrate had sought to enlist the king and his army in a battle against some Basotho rebels in what became known as the Gun War of 1880-1881. In return, the amaMpondomise would receive guns and ammunition.

Hope maintained that the Basotho rebels were refusing to hand over their guns in defiance of the Peace Preservation Act of 1878, which required all native peoples to surrender their guns and ammunition to the government of the Cape Colony’s British Kaffraria.

The murder of Hope and some of his men would cost the amaMpondomise their kingdom, but not before they had destroyed the magistrate’s offices and jail. Mhlontlo, who teetered on the brink of prevarication, had decided to spare the general white populace as well as white people he saw as not being part of the state. “We should be killing everyone whilst we have the chance,” says an exasperated Malangana, the king’s brother and interpreter. “They will call other white people and make war on us.”

Besides fictionalising actual events, and thereby forcing us to re-examine them, there are other allegorical parallels to modern-day South Africa in Little Suns. There are moving scenes in which the amaMpondomise, beset by taxes and the injustices of a court system that humiliated them with physical beatings, take over the magistrate’s court after Hope’s murder and stage mock trials.

These scenes coexist with others, years later. Notably, long after the status quo has been restored to the colony, a hobbling, tamed Malangana confronts a group of white women playing bowls at the Residency, where Hope had lived during his tenure as magistrate.

As the women insult him, calling him a vagabond and telling him to “foot-sack”, as they amusingly try out “Trek-Boer” expletives, Malangana wants them to remember that he is “the man who killed Hamilton Hope”. When they dismissively remind him that history records Mhlontlo as the killer, he retorts: “My spear tasted his heart even though he was already dead.”

One gets the distinct sense from reading Little Suns that, rather than launch diatribes about the state of South African literature, Mda is at a point where he’d rather let his art continue to do the talking.

By way of contributing to issues emanating from debate sparked at last year’s Franschhoek literary festival, Mda threw a once-off missive in which he told arts writer Charl Blignaut that he too had taken a decision to boycott the festival and other lily-white ones as he felt like a “dancing monkey”. There were shock waves, but the prolific writer just left it at that.

“Issues of decolonisation do not come with you guys [the younger generation]. We spoke about them,” he says, his pitch rising a notch. “The guys you are reading now are guys of our generation that we spoke about a long time ago. That’s why we are even tired of talking.”

The demise of apartheid, says Mda, freed him to explore the possibilities within the historical novel, where one can look at, for example, the methods and modalities of colonisation. But largely, Mda views the country’s literary trajectory through an optimist’s prism.

“Just in terms of quantity only, the novels that have been published in the last 10 years are greater in number than all the novels that we have published in the whole history of novel writing in South Africa – just in the last 10 years. And many of them are by these young and dynamic writers who come with many different themes in dealing with their situation today.”

He sneers at a thread of the debate that suggests that black South African writers working in English operate within narrow parameters, flinging a finite clutch of narratives to white audiences in anodyne prose, a product, no doubt, of an entrenched value chain.

“The whole rubbish of writers should be doing this or that is a complete bungle,” says Mda. “I liked what Nakhane Touré [a writer he was in public conversation with earlier this week] is doing … because he is being creative, he is being an artist and taking a direction that is different from most mainstream art. But there is nothing new there. The avant-gardists have been writing like that, the post-modernists and the post-post-modernists.”

Mda believes that if writers are influential enough they influence society, suggesting he finds comfort in the dialectical order of things.

By extension, he holds similar views on how writers can circumvent the prevailing infrastructure. “There are many writers who don’t even bother with the establishment. They write something and put it online. Rachel’s Blue was first published online as a Kindle novel. After a year being on Kindle, it got published by the establishment. They [had to] bid for it [my novel].”

For now, Mda is not ashamed of the creature comforts that come with playing the game the best way he knows how.

When the conversation moves to the use of English in telling African stories, Mda, a fluent Sesotho and isiXhosa speaker, is momentarily caustic. “I make a living from these books. They are published here, then they are published all over the world. And I get royalties, which are banked here at Absa. In other words, they benefit South Africa. It’s a job and I do it in the language of the market.”

With Little Suns, Mda not only advances the “speakability” of the current South African condition by offering compelling redrafts of colonial history, but also forces us to confront, viscerally, what that history looked like.

In so doing, he forces us to confront our current complicity in these systems and just what it might take to undo it.

Read more from Kwanele Sosibo or follow him on Twitter