It was, agreed both winners, a “yuge” night in American politics. A record number of New Hampshire voters queued in freezing traffic jams until well after polls were due to close to pick a Democrat and a Republican candidate to run for president.

The rebellion against the political establishment was overwhelming: Bernie Sanders, a self-declared democratic socialist and the independent senator from Vermont, had trounced Hillary Clinton in the Democratic race by almost 22 points. A bombastic property tycoon called Donald Trump had flattened a crop of Republican veterans who were once seen as the strongest field of conservative candidates for a generation.

This first primary of the United States election season is, like the Iowa caucuses that preceded it last week, only a small staging post on the long route to securing a party nomination. In fact, New Hampshire has not picked the eventual president since George HW Bush won the primary in 1988.

But results in both early states – including a win for maverick Texas senator Ted Cruz in Iowa – now point to political insurgencies that may drag on for months, with potentially profound consequences for the direction of national politics and for whoever eventually wins.

For though they come from diametrically opposing ends of the political spectrum, Sanders and Trump share more in common than just a distinctively New York approach to pronouncing the word “huge”.

From their very different perspectives, both rail against the system of campaign finance that has come to dominate US elections but is now being questioned by many.

On one side, the property billionaire claims to have seen how easy it is to buy political influence and is choosing to renounce his old ways by paying for this campaign himself. On the other, Sanders is beating Clinton’s rich backers by raising $20-million a month from a record number of small contributors giving him an average of just $27 each.

Sanders told ecstatic supporters at a victory party: “We have sent a message that will echo from Wall Street to Washington, from Maine to California, and that is that the government of our great country belongs to all of the people and not just a handful of wealthy campaign contributors and their Super Pacs [political action committees].

“Tonight, we served notice to the political and economic establishment of this country that the American people will not continue to accept a corrupt campaign finance system that is undermining American democracy,” he added.

Shortly after Clinton rang Sanders to concede defeat in a campaign that has been dominated by claims of her links to Wall Street and her receipt of lucrative speaking fees from Goldman Sachs, Sanders’s supporters started singing: “We don’t need no Super Pac” to the tune of the Talking Heads song Burning Down the House. Given what a challenge his new way of politics poses to a system that even Barack Obama relied heavily on, the original lyric may have been just as apt.

As stock markets around the world once again continued their recent rout, here too were a pair of politicians declaring very different wars on the world’s economic status quo: both promising to end 70 years of US-led free-trade policy and – with varying conviction at least – both arguing the country should provide universal healthcare.

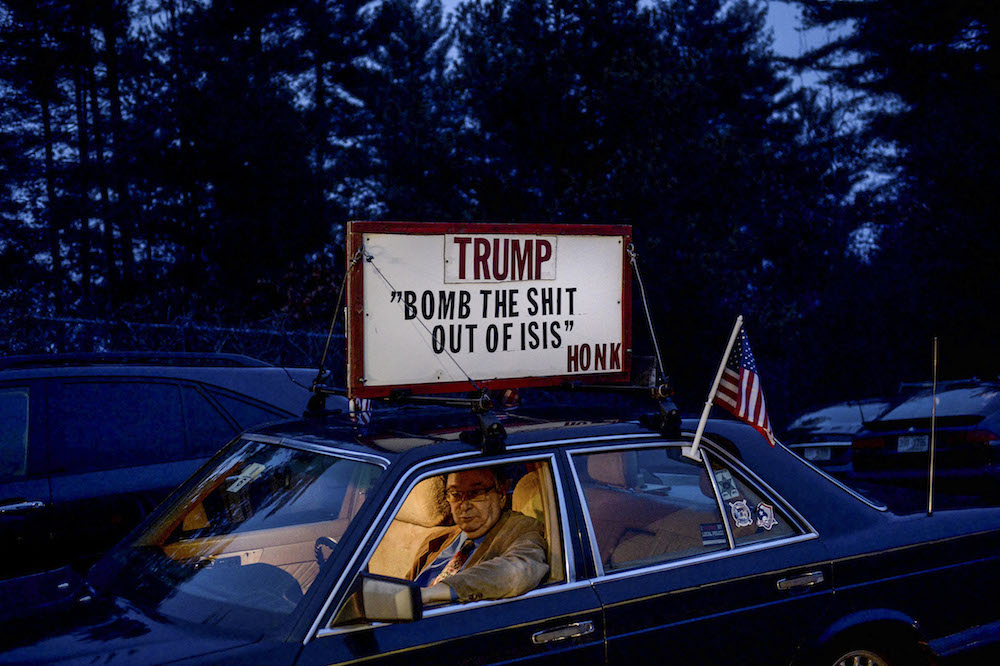

Instead of parroting the standard boasts of American exceptionalism, both claim the US is losing the key battles of the 21st century: Sanders pointing to soaring income inequality as a sign that the American dream is dead; Trump – his mantra “Make America Great Again” on every baseball cap – arguing the country is losing wars against Islamic extremism and Chinese mercantalism that Obama has been too weak to fight.

“We are going to start winning again,” Trump told his victory party. “We don’t win on trade. We don’t win with the military. We need to win with Isis [Islamic State].”

The parallels between the two men on policy matters are extremely limited, of course, and even highlighting their shared anti-establishment approach will fill both sets of supporters with horror, but there are stylistic similarities that are hard for outsiders to ignore.

Much as Trump accuses “scum” in the media of misrepresenting him and being overly politically correct when reporting on his seemingly ever more offensive insults, Sanders slams the “corporately owned press” for failing to take his ideas for social reform seriously enough.

“The people of New Hampshire have sent a profound message to the political establishment, to the economic establishment and, by the way, to the media establishment,” he told supporters on Tuesday night, who turned to shake their fists and stomp their feet at journalists – much as Trump’s supporters do at his rallies.

Supporters of both candidates are presented with a variety of villains to choose from when cheering their man as the rallies turn into pantomime. Trump focuses on racial and religious minorities as scapegoats for his vision of what is wrong with the US: Mexican immigrants are dismissed as rapists and drug dealers, to be deported in their millions and kept from returning by a wall on the border that their government will be forced to pay for; Trump crowds yell “Mexico!” on cue as he asks them who will pay for the wall. Muslims across the world are all deemed such a potential terrorist threat that they should also be kept from entering the US.

Appealing to the disaffected: Though they come from diametrically opposing ends of the political spectrum, Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump both rail against the system of campaign finance that has come to dominate US elections. (Darren McCollester/Getty)

The Sanders world view could not be more different, seeking rapprochement with the Muslim world and demanding sweeping immigration reform, but he has his own, more powerful bogeymen – largely, wealthy companies that are blamed for exploiting the middle class.

“Walmart!” shout his supporters, in an echo of the Trump gatherings, as the supermarket giant is paraded as a regular target. Bernie, as he is universally known by supporters, argues that its low wages and high profits represent a colossal subsidy from taxpayers because many of its workers are so poor they need help from government welfare programmes.

Goldman Sachs is similarly held up as an exemplar of Wall Street greed and an investment banking business model that he claims is based on little more than fleecing customers.

Yet it is perhaps no coincidence that the two companies Sanders most frequently chooses to exemplify the “rigged economy” both have strong ties to the Clinton family. The former first lady was a board director of Walmart for six years when she lived in its home state of Arkansas while her husband, Bill, was governor.

And, quite apart from the now infamous $600 000 Clinton took in speaking fees from Goldman Sachs after leaving the state department, her daughter, Chelsea, is married to a former employee of the bank. Campaign volunteers who canvassed for Sanders in the past few days in New Hampshire say it was these alleged ties to Wall Street and Clinton’s use of big-money campaign contributions that came up most among voters.

Given this, it was perhaps no surprise that among the first promises made by Clinton during her speech to disappointed supporters on Tuesday night were to take new steps toward reforming Wall Street and campaign finance.

The scale of her defeat on Tuesday nevertheless points to strategic challenges for Clinton that could hurt her in other states – particularly the “Super Tuesday” states voting on March 1 that once looked much more hospitable.

According to exit polling in New Hampshire, the only demographics Clinton won in the state were those aged over 65 and those earning more than $200 000 a year – a reversal of her comeback against Obama in 2008 when she won the state with the help of blue-collar workers.

It is waning support from younger voters and women that may also prompt a rethink of Clinton’s strategy ahead of the key battle for the Nevada caucuses next week.

Sanders campaign adviser Tad Devine told the Guardian he is now hopeful of tempting Latino-dominated service-sector unions in the state to part company with labour leadership in Washington and fight Clinton hard.

Though Clinton had until recently looked stronger in polling for the next few states, particularly among African-American voters in the South, Sanders flew straight to New York on Wednesday to seek the endorsement of key community leader and media host Reverend Al Sharpton, and will spend heavily on television advertising from Wednesday onwards.

At some point, many pundits still expect, more moderate candidates will catch both Trump and Sanders. Clinton could yet blow her opponent out of the water quickly if she holds Nevada and takes South Carolina with a decisive win among minorities. March will probably be a decisive month, starting with the Super Tuesday test across 13 states.

Among Republicans, governors John Kasich and Jeb Bush are slugging it out in a war of words to see who can be persuaded to stand aside gracefully and let the other take on the mantle of Trump-slayer.

But the reasons why voters turned out in droves to vote for Trump and Sanders in New Hampshire on Tuesday are not unique to the quirky little state, despite its outsize role in the primary process.

Even if they eventually fall by the wayside, their threat to the establishment status quo in the US may yet also tempt other independent challengers such as former New York mayor and businessman Michael Bloomberg.

And, with plenty of money of their own and a new sense of momentum, it’s hard to see Trump or Sanders stepping down easily as insurgent champions of this very frustrated new breed of voters anytime soon. – © Guardian News & Media 2016