Beasts of No Nation

Confronted with questions about why the jury of the 2016 Berlin International Film Festival had no people of colour serving on it, jury president – and three-time Oscar winner – Meryl Streep said: “We are all Africans, really.”

In the wake of the #OscarsSoWhite controversy about limited diversity in the film industry, Streep’s comment added fuel to the fire and prompted a storm of criticism about what was seen as a patronising attempt to silence the debate.

Few of the critiques of Streep’s comment focus on its original context. It was actually made in response to an Egyptian journalist asking her whether she knew anything about the Middle East or Africa and about films made in these regions. She admitted she didn’t.

At best, Streep’s comment was a clumsy attempt to show solidarity. But what it underlined was the continued absence of Africans and African film-making from international film festivals and mainstream cinema. If we are all Africans, why are we not watching African films?

D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915) glorifies the Ku Klux Klan. (Supplied)

Racism is a charge that could be levelled at cinema from its very inception. Film professor Robert Stam says that, of all the conditions that attended cinema’s birth, “it is cinema’s coincidence with imperialism that has been least studied”.

Many films made in the early 20th century whitewash black narratives and characters, and justify white violence against people of colour as righteous. DW Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), set during the American Civil War, glorifies the Ku Klux Klan. Instead of being condemned, the film is hailed as a “masterpiece” for its pioneering film techniques.

Although Griffith has been canonised, black and African filmmakers have struggled to get their work featured at international festivals or picked up by distributors and exhibitors, even after the strides achieved by the civil rights and independence movements. An instructive example is the representation of African films at Cannes, the most prestigious international film festival.

Since Cannes began in 1946, a mere 3% of the films in competition have been African. And from 1946 to 2013, only 14 African films won prizes. Only one African film – Chronicle of the Year of Embers (1975) – has ever won the Palme d’Or.

Birth of a Nation filmmaker Nate Parker was told that his film (pictured above) would not succeed. (Fox Searchlight Pictures)

The decision was so contentious that the jury members and film-makers received death threats, and required police protection as they were leaving the Palais des Festivals. This is because the film dared to tell a story about the Algerian War of Independence from the Algerian, rather than the French, perspective.

Although the “father of African cinema”, Senegalese director Ousmane Sembène, was invited to be a Cannes jury member as early as 1967, few people of colour have since been welcomed into this inner circle.

In contrast, films that use Africa as a backdrop for white adventure narratives are still widely screened globally – such as Out of Africa (1985), starring Streep herself, which won seven Oscars and grossed more than $100?million worldwide. Why?

The answer, of course, encompasses racism but also goes beyond it. It has to do with the perception that African and black films will not attract audiences. When he set out to make a film about the revolutionary slave Nat Turner, filmmaker Nate Parker was told that such a film would not succeed because “movies with black leads don’t play internationally”.

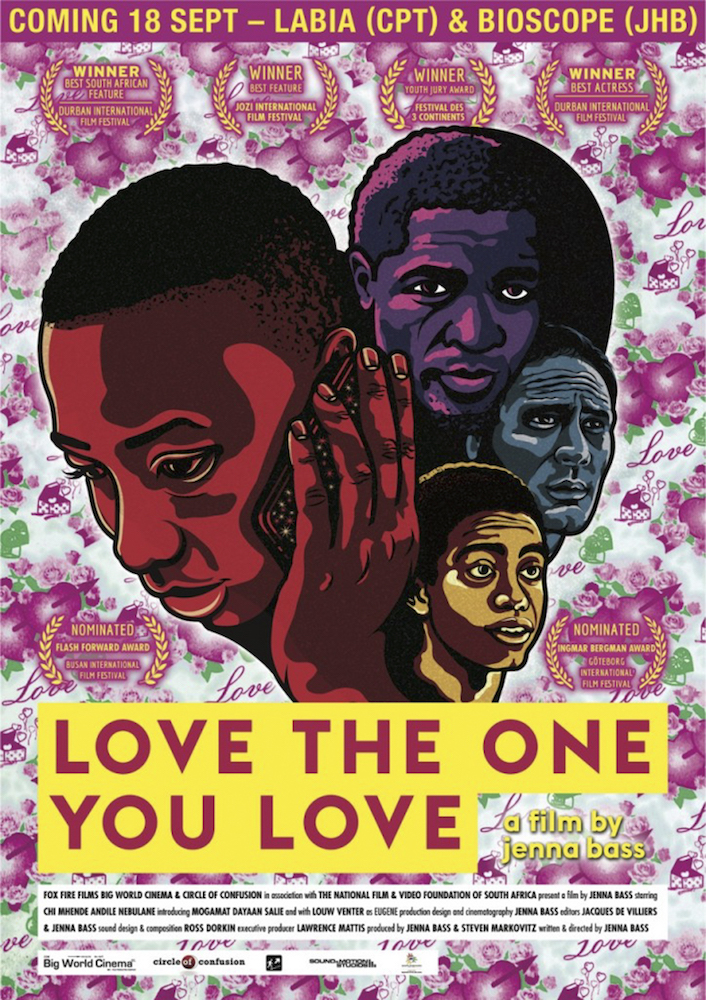

Films like Love The One You Love offer diverse narratives about Africa. (Big World Cinema)

A few weeks ago, Turner’s film – purposefully titled The Birth of a Nation – secured the most lucrative distribution deal ever recorded at the Sundance Film Festival: $17.5?million from Fox Searchlight Pictures. The film was also included in a rich programme of black and African films screened at the 2016 Pan-African Film Festival in Los Angeles.

There are other signs that the industry is transforming.

• Franklin Leonard’s The Black List (an annual survey of the “most liked” screenplays that have not yet been produced) has helped to catapult screenwriters of colour into the limelight;

• The Toronto International Film Festival’s artistic director, Cameron Bailey, is an African film specialist whose connection with film production on the continent goes back 25 years;

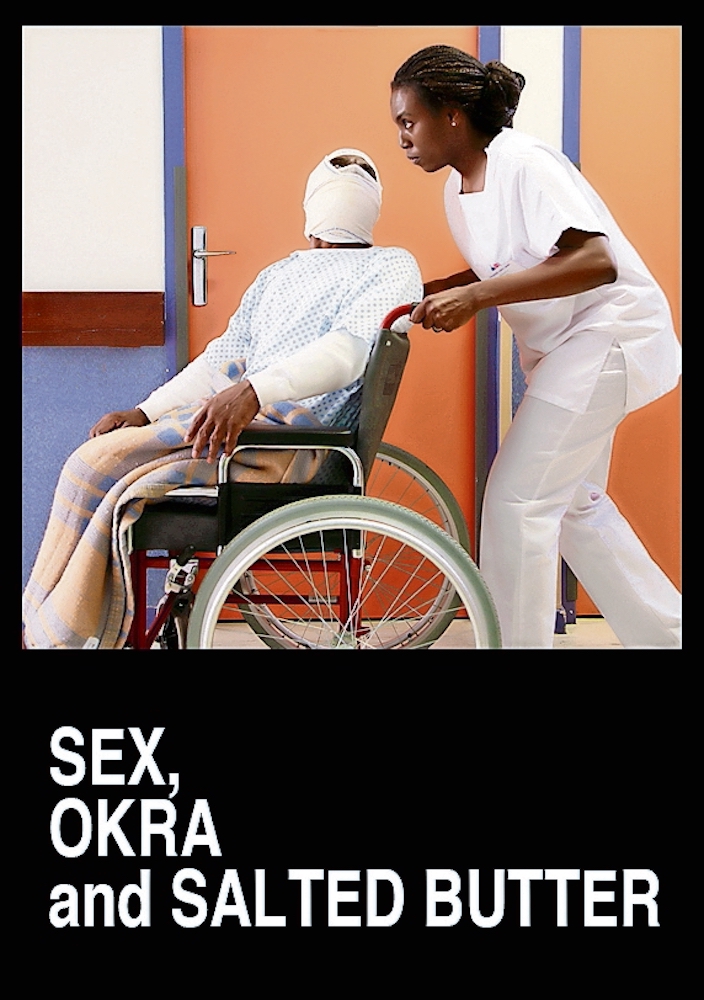

Sex Okra And Salted Butter was originally produced for television. (Africa Picture House)

• The Sydney Film Festival’s director, Nashen Moodley, is a South African who is also the curator of the Asia-Africa programme at the Dubai International Film Festival;

• Since 2006, the Dubai festival has also run the lucrative Muhr awards for Arab, Asian and African filmmakers; and

• Selma director Ava DuVernay has recently started a film distribution company, Array, through which she supports African films such as Ayanda (2015), a South African coming-of-age film directed by Sara Blecher.

But it is the internet – as the new frontier of film distribution – that will be the real yardstick of change. There are some promising signs here, too, with the recent arrival of African video-on-demand platforms such as AfricaFilms.tv, buni.tv and iroko.tv.

It is not simply an issue of black lead actors, though. It is a sobering fact that the film about Africa that has performed best on Netflix is Beasts of No Nation (starring Idris Elba), a child-soldier movie that rehashes stereotypes of an endemically violent continent.

We need more diverse narratives about Africa – the ones in films like Sex, Okra and Salted Butter (2008), Pumzi (2009), Love the One You Love (2015) and so many others.

And it is not just up to the film industry. As individuals we can make a difference through the films we choose to see. I boycotted the Oscars on February 28. I had something much more exciting to do: watching Malian filmmaker Souleymane Cissé’s film Yeelen (1987) and discussing it with him at the CinemAfrica Film Festival in Stockholm.

We need to vote with our cinema tickets and our internet clicks. And if Hollywood refuses to change itself, why do we even give it the time of day? – theconversation.com

Lindiwe Dovey is a senior lecturer in African film and performance arts at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.