Albert Adams is one of the names on Marilyn Martin's list of overlooked artists she wants to put on the art map.

“I am fascinated by those who have been left behind or forgotten,” says Marilyn Martin, the co-curator of Bonds of Memory, a retrospective of Albert Adams’s paintings at the Smac Gallery in Cape Town.

The curator, who carved out her place in (art) history as the director of the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town, has compiled a list of overlooked artists she wants to put on the art map. Some of those names, such as Louis Maqhubela, who is known for his modernist abstraction, have already been ticked off that list.

Martin thought she had ticked Albert Adams off the list after a 2007 retrospective of his work at the national gallery, which she curated with colleague Joe Dolby. It coincided with the publication of a book of essays on Adams penned by, among others, Peter Clarke, the Cape Town artist who had grown up with Adams. But it seems Adams didn’t become a household name, showing that a book isn’t always enough.

“People forget so quickly,” says Martin.

She and Dolby hope this new retrospective of mostly paintings Adams created between the 1950s and 2000s — drawn from a collection held previously by the University of Newcastle in the United Kingdom — will reignite interest in the artist, and sustain it. Another iteration in Stellenbosch before a countrywide tour of the exhibition next year is intended to help achieve the goal of solidifying Adams’s place in history, and in our collective memory.

This is usually the type of work a public art institution undertakes, rather than a commercial one, but this is not the barrier to Martin and Dolby’s objective. There are a number of other obstacles. These include the fact that it is not clear where in the big art history scheme of things Adams “belongs”, given he was somewhat of a chameleon artist who adopted a variety of different styles influenced by British and German artists. It doesn’t help matters that he died before giving the curators enough insight into what motivated his art; so much of what we know is based on their suppositions.

It is likely, given his reticence towards commercial galleries, that he may have been reluctant to show his art, or perhaps he was sceptical about how it would be framed by someone else. He and his partner, Edward Glennon, curated a show of Adams’s work at the Irma Stern gallery in Cape Town.

Untitled (Four Figures with Pitchforks) c1950. Chalk on paper.

Another complication is his life story, which does not conform to the “struggling political artist in exile” narrative. He wasn’t interested in politics, claim Martin and Dolby, and appears to have flourished in his self-imposed exile from the country of his birth. In a way, it is almost as if Adams quietly resisted being canonised. This puzzle makes his art all the more poetic and attractive, and is fitting given that he was a “complicated man”, says Martin.

Adams taught art history, so one can assume he knew well enough the machinations around unearthing overlooked art or artists. In South Africa, such activities are politically and racially fraught. The sensitivities about which and how supposedly overlooked artists are brought to light cannot be underestimated. Martin and Dolby do not appear to suffer from an overt “white saviour” complex — Martin’s list of overlooked artists includes white men.

As always in this country, one can’t put race aside. This exhibition is subtly haunted by Adams’s racial identity as a coloured person, although it is not something to which he drew attention or wanted to be highlighted, according to Martin.

“His work needs to be assessed on its own terms,” she says.

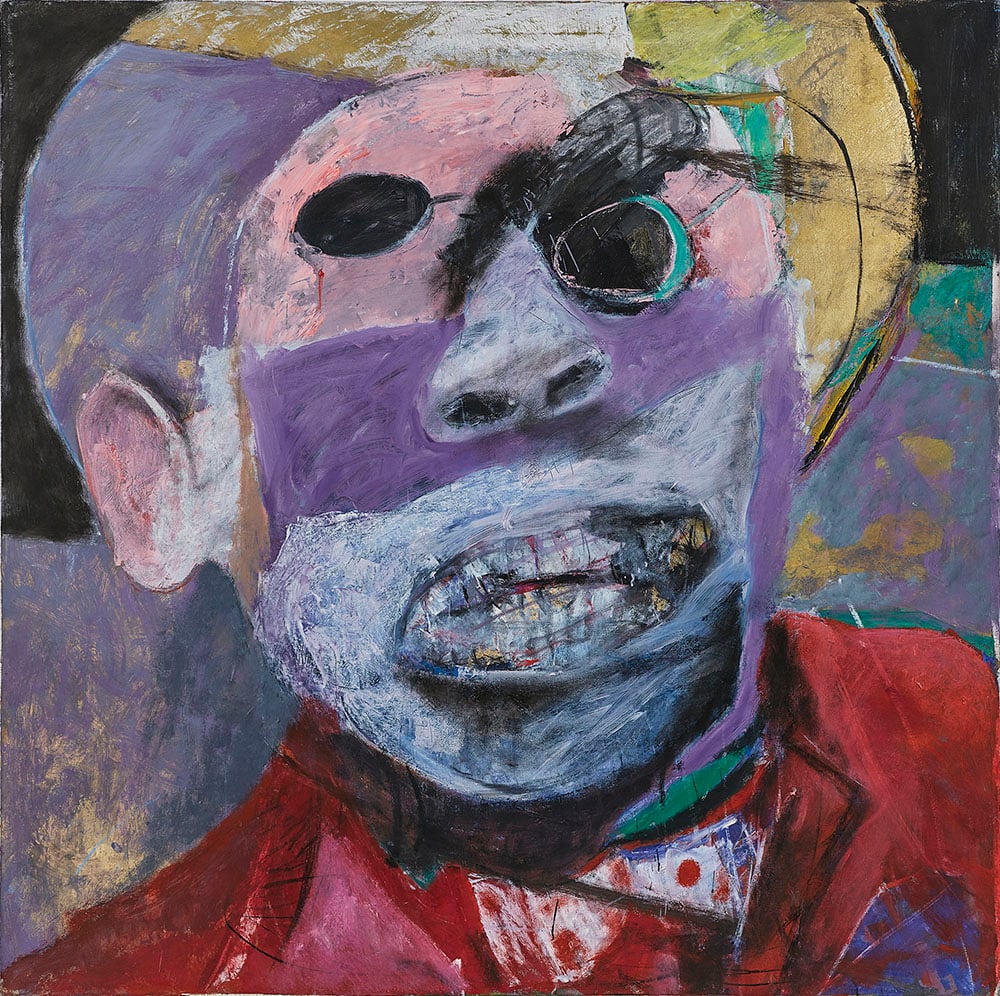

But his dark rendering of the recurring motif of a minstrel from the Kaapse Klopse festival led Smac Gallery owner Baylon Sandri to conclude that Adams’s significance is tied to his racial identity or aspects of it with which the artist wrestled. Minstrels are associated with stereotypical ideas about the coloured population in the Western Cape and Adams had a compulsion to paint self-portraits, leading Sandri to this conclusion.

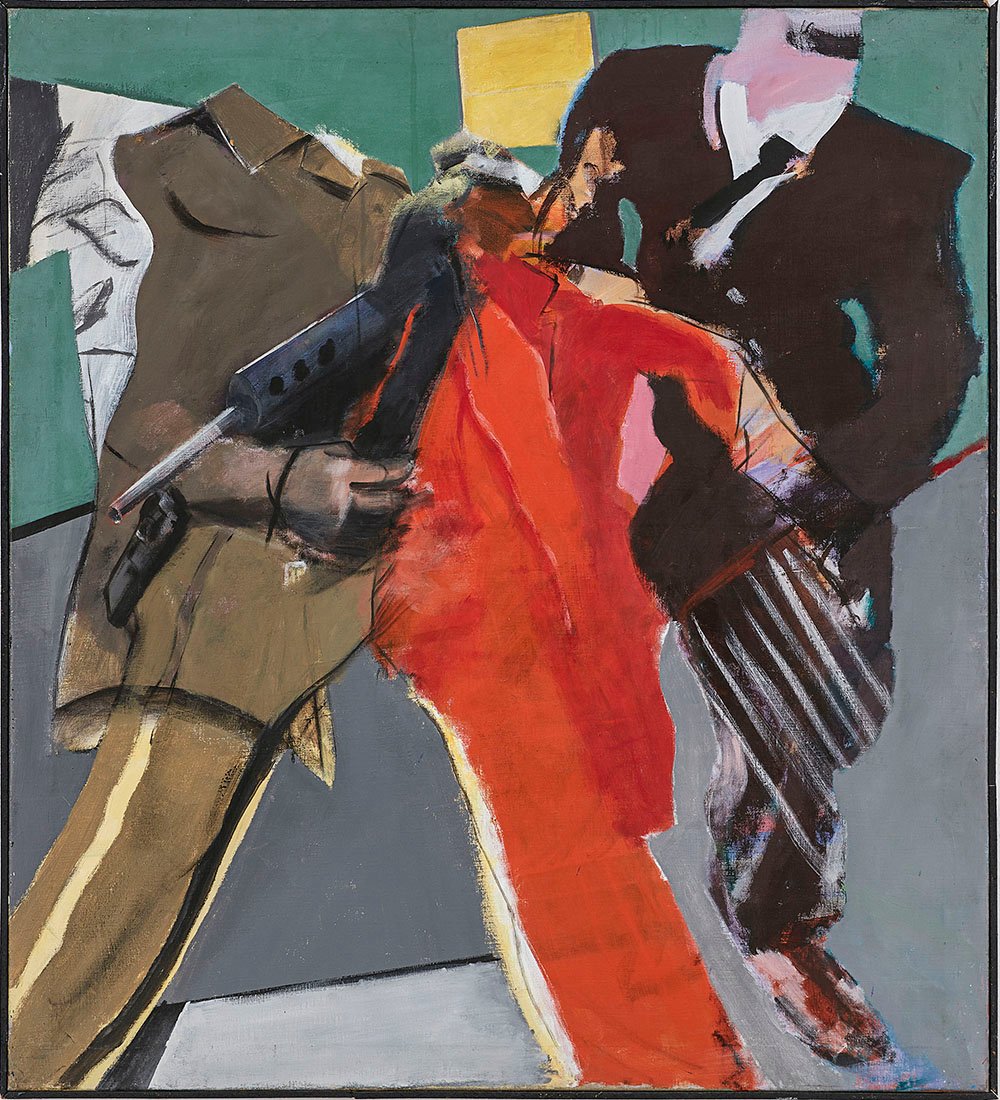

The Captive 1982. Acrylic on canvas.

Adams would not have been able to overlook his race, because it prevented him from enrolling at the University of Cape Town’s Michaelis School of Fine Art. Being homosexual apparently made it difficult for him to feel a sense of belonging in his community, too.

Presumably these circumstances encouraged him to study abroad, at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, before enrolling for other classes in Italy and Germany, where he apparently absorbed the German Expressionist mode.

European artists, including Picasso, influenced Adams heavily. This can be seen in his triptych dubbed South Africa 1959, which is informally known as the African Guernica in reference to Picasso’s famous work relaying the violence and chaos of the Spanish Civil War. He settled in London until his death in 2006 and his art reflects British sources of inspiration, mostly from the School of London painters, who were pursuing forms of figurative painting amid the trend for abstraction in the 1970s.

The Captive, a semi-figurative work reflecting three spliced male figures, brings to mind the bright collage-type paintings of RB Kitaj, who came up with the term School of London. Cyclist with Monkey and other works featuring this animal make one think of Francis Bacon’s work. In this way, Adams seems to have slipped under the skin of many different modes of expression.

“This made him an individual. He wasn’t part of any movement,” says Dolby. “I think that is his strength,” adds Martin.

Celebration Head 2002. Oil on canvas.

In today’s art world, a lack of distinctiveness might not have won him applause. Artists are under pressure to develop a characteristic language that is recognisable, particularly to buyers. Selling his art does not seem to have been a driving motivation for Adams.

Adams may have moved in the same circles as Irma Stern when he was based in Cape Town and then visited the city later on, but he does not appear to have forged strong alliances with the art community in London. This may have had something to do with British class snobbery, says Dolby.

Adams may have created work in isolation, but he was not a recluse. He loved teaching and, much to most people’s surprise, thrived on it, despite working at tough schools in London’s East End. He appears to have settled happily into life in England with Glennon. Martin and Dolby describe him as a charming, sophisticated, knowledgeable raconteur, although their interactions with him appear to have been limited, most often to discussions around funding for his 2007 retrospective, which he did not live to see.

He may have been reticent about showing his art or discerning about the contexts in which he did, but he appears to have craved praise. Martin claims he was deeply disappointed that she did not rave about some of the works he had shown her.

Martin and Dolby favour his drawings over his paintings. “We both feel the more graphic and gestural and restrained use of colour works better,” says Dolby.

But his paintings, as always, are of more value to buyers and it is the sale of them at a commercial space such as Smac that may ultimately put Adams on that elusive art map.

Bonds of Memory is on show at the Smac Gallery in Cape Town until May 21.

This article was Independently generated by IncorrigibleCorrigall and subsidised by the gallery.