Making the grade: Ecstatic matrics receive their final marks. Struggling grade 12s who have been pushed through may be able to write some exams at year-end and the rest at a later stage.

A new plan by the basic education department will see the publication of not one but three different pass rates for matrics at the end of 2016.

The plan, which has been welcomed by academics, makes provision for the pass percentage of progressed learners to be reported separately.

These are children who have failed grade 11 twice but have been promoted to grade 12, despite not meeting the promotion requirements.

Previously, only the national and provincial pass rates were publicised.

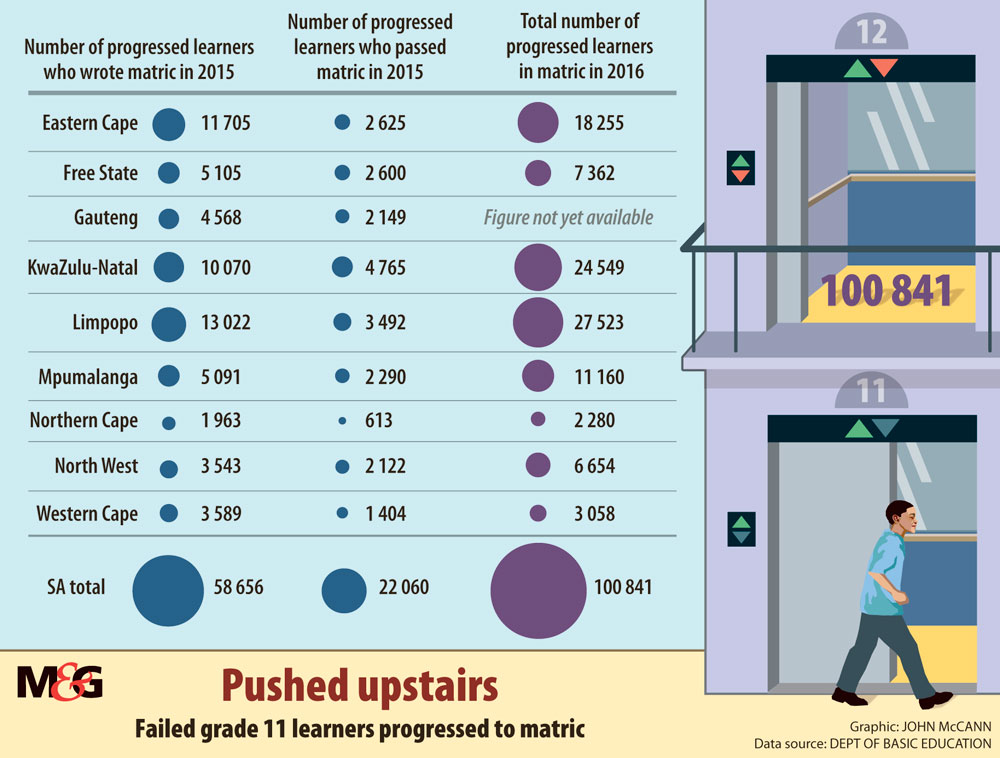

Last year’s national matric pass rate of 70.7% would have been 74.1% if 58 656 progressed learners had not sat for the exams. Only 37.6% of this group passed.

So far this year, there are 100 841 progressed learners in matric in eight provinces. Gauteng’s education department was still capturing registration figures at the time the statistic was compiled.

The basic education department has been encouraging provinces to “progress” those who have repeated grade 11 more than once, as well as those who are deemed overage, since the policy was promulgated in 2013.

According to the draft amendment regulations on the senior certificate exams, which were gazetted recently, the national and provincial pass rates would each be broken down into three sets of statistics: the combined pass rate of all matriculants, the pass percentage of progressed learners, and the pass percentage of matriculants excluding the progressed group.

Rufus Poliah, chief director for national assessments and public exams in the department of basic education, said the new reporting method would provide the public with more detailed information.

“In implementing the policy on progressed learners, the department has been totally upfront and there is no intention to ‘massage’ the results. It is important to monitor the performance of progressed learners hence the separate reporting on their performance.”

He said it was an open and transparent method of reporting “so as to obviate the criticism that the department is concealing vital information”.

Speaking in his personal capacity, John Volmink, acting vice-chancellor of the Durban University of Technology, said that he did not believe the department was trying to “fudge” the national pass rate by announcing three pass rates.

“On the contrary, I think it’s an honest attempt to recognise that not all learners are equally prepared to write the grade 12 exams.

“If we look at the outcomes, the achievements, separately over time we will become more intelligent about how different or how similar the two groups are.”

Volmink said there was always the assumption that the matric cohort from year to year remained the same.

“Last year showed us very clearly that the matric cohort is different in many ways to other cohorts and the results also demonstrated that. I think that, over time, if we disaggregate it in part we will be able to see how different the two populations are.”

He added that the progression policy was important because it was not in anyone’s best interest to keep people who are supposed to be in school for 12 years for 14 to 16 years.

“The progression policy is really one of social justice and making sure that we don’t clog up the system with people that don’t want to be in school,” Volmink said. “It’s common cause that, if somebody fails more than twice, the likelihood that they would leave school is extremely high.”

Nick Taylor, a research fellow at JET Education Services, said: “If this is part of a general scheme to try to break down the matric results into different indicators, I think we are going in the right direction.

“I think it’s very interesting that a number of progressed learners passed last year. What does that say about the system?

“They failed grade 11 and passed matric. You are always going to get a bit of that because kids work harder in matric, but maybe it says something about teachers’ inability to assess accurately in grade 11.”

“It’s easy to manipulate the pass rate,” said Taylor. “Progressing learners is one way of preventing the pass rate from being manipulated. Principals can manipulate the pass rate by holding kids back or even kicking [those who are weak academically] out of school.”

But he said other indicators of success should be targeted, such as the teaching of English first additional language. “One of the biggest problems in the university sector is that these kids are hopelessly unprepared in terms of their language and cognitive skills.”

“For me,” he said, “the most important element in trying to improve the standard of schooling is to improve the standard of teaching English first additional language.”

Mafu Rakometsi, chief executive of matric quality assurance body Umalusi, cautiously welcomed the bid to have three separate pass rates. “This disaggregation of learners will serve the purpose of us understanding the 2016 cohort better, that there are so many percent progressed learners and so many percent nonprogressed learners. When we deal with this exam and then debate and discuss, we will be fully aware of the cohort we are dealing with.”

He said that, at the end of last year, Umalusi was criticised by education commentators for not having separated the progressed learners from the other learners. “They were saying that we just took them as a uniform group. They were saying we dealt with this group [the 2015 matrics] as if it was a homo-genous group when doing our quality assurance processes when, in fact, they were not homogenous.”

Said Rakometsi of the disaggregation: “We are still in discussions with the department on this matter. We have not reached finality on it.”

According to the draft document, learners progressed to grade 12 should be allowed to write some subjects at the end of the year and the remainder in a subsequent exam. But those who have demonstrated “acceptable achievement” in six subjects will be allowed to write all of them during the exam window.