Rough road: Since the introduction of e-tolling in 2013

The South African National Roads Agency (Sanral) finds itself in an ever-worsening financial vortex as motorists hold firm in boycotting the electronic tolling of Gauteng’s highways.

Mounting unpaid accounts stood at R7.2-billion at the end of March, with the largest single unpaid bill topping R35-million, and three million road users remain in arrears.

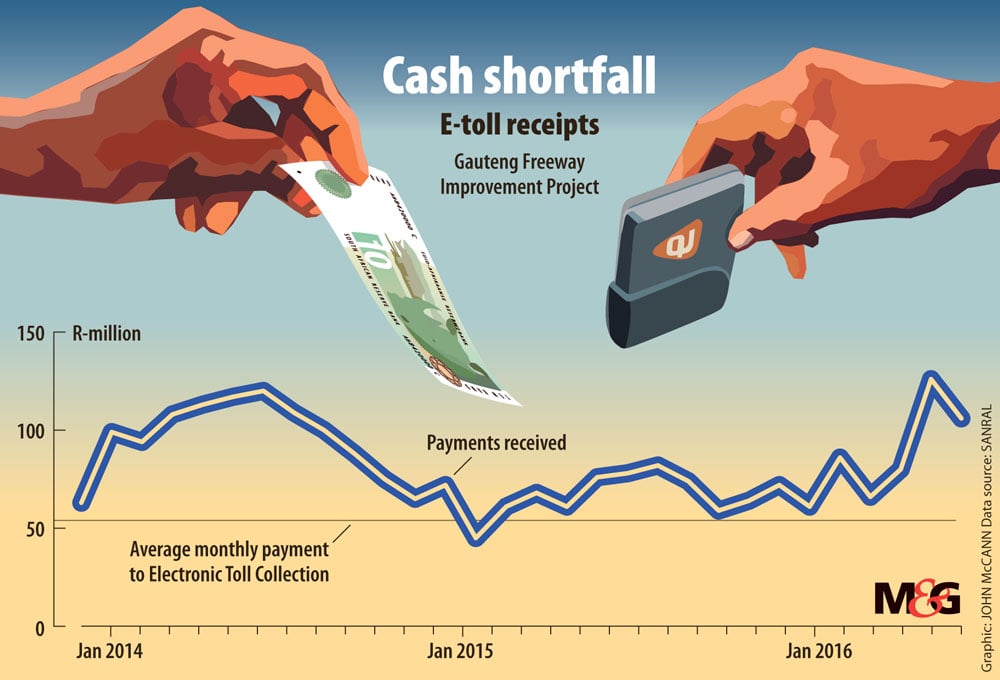

Collections are low, and in one month the entire e-toll collection did not match the average R54-million a month paid to the company that operates the tolling.

Sanral’s revenue shortfalls have seen its debt rocket from R6.2-billion in 2007 to R36.7-billion in 2015.

Now the agency has prepared 6 500 summonses that are in the process of being issued and served to non-paying users. But a long-time foe, the Organisation Undoing Tax Abuse (Outa), is gearing up to fight the matter in the courts.

Outa said it is in the early phases of preparing a legal action but it is searching for a “workable” arrangement in finalising a case to test the legality of the tolling scheme. Although e-tolling is not unlawful, it may not be enforceable, said Wayne Duvenage, the Outa chairperson.

Since the introduction of e-tolling in December 2013, monthly collections have at times struggled to meet even revised forecasts.

Sanral collected R120-million in the month of June 2014 — before the Gauteng government announced a review of the e-toll system in July that year.

Collections remained between R45-million and R82-million during 2015. This year a 60% discount on historic e-toll debt saw Sanral realise collections of R126-million in April and R106-million in May.

But revenues have varied greatly, which means that, in some months, Sanral may not even receive sufficient e-toll revenue to cover the average monthly payment of R54-million to the Electronic Toll Collection (ETC), now wholly owned by the Austrian company Kapsch TrafficCom.

“Payment to ETC takes place on a schedule of payment items and depends on the services delivered for the month, such as the number of invoices printed and posted, calls received and made, etcetera. The payment certificate includes also costs such as administration costs, communication costs, banking fees, facilities (including maintenance and asset refresh), rates and taxes,” he said.

Sanral originally estimated the ETC would take 17c of every rand paid by users of Gauteng highways but, with the high levels of non-payment, the ETC’s fee now accounts for a significant part of monthly collections.

Sanral said the contract with ETC was tendered for and includes an eight-year operating period.

Duvenage said Sanral is becoming increasingly desperate. “It is a defunct scheme that is not even paying for the collection process, let alone the toll roads,” he said.

Of more than 1.4-million vehicles with an e-tag, most — just over 1.3-million vehicles — are in good standing, said Vusi Mona, Sanral’s general manager of communications. He said there are just slightly fewer than three million accounts with amounts owing. Of these, 1.2-million owe less than R500 each.

To pay its bills, Sanral continues to rack up debt. The agency’s financials show that its borrowings (recorded under non-current liabilities) grew from R6.2-billion in 2007 to R31.7-billion in 2011 and to R36.7-billion in 2015.

The treasury provides allocations for non-toll roads and Sanral can’t raise debt for them. It can only raise debt for tolled roads, which account for 15% of its total road network. Furthermore, about 40% of the tolled roads are awarded to concessionaires, which are financed by private sector capital on a “build, operate and transfer” basis.

This means that Sanral gets revenue from just 1 832km of its 3 120km of toll roads.

According to Mona, the Gauteng Freeway Improvement Project (GFIP), which refers to the upgraded highways now subject to e-tolling, represents about half of Sanral’s debt portfolio.

At 200km in length, the project amounts to 10% of Sanral-operated toll roads, and less than 1% of Sanral’s national road network of 21 403km.

Meanwhile, the tenders for road construction have been found by the competition authorities to have been subject to collusion and inflated prices. Sanral this year lodged civil claims of R600-million and R760-million against some of these construction companies.

Raising debt is part of a continuous programme to fund Sanral’s toll portfolio, said Mona.

“As with most long-term infrastructure, the repayment period is over several financial years. For toll roads, this is normally around 15 to 25 years, depending on the traffic, tariff and real rate. Funds raised are, therefore, applied for continuous maintenance of the road, operations and servicing the debt.”

In its last annual report, 2015, the agency noted it would hold more cash than usual so that it can still cover expenses in the event of a further decline in the payments for the GFIP, or in the event of a failed bond auction. As of March 31 2015, cash and cash equivalents held were R9.8-billion, more than double the R4.1-billion held in 2014.

Sanral has held a number of failed bond auctions, with not enough subscribers, in the past year and has cancelled several others in anticipation of undersubscription.

It has two types of debt — bonds that are backed by a government guarantee and bonds that are not. The former is the easier kind of debt for investors to buy into, said Gordon Kerr, a fixed income expert at Rand Merchant Bank.

“They haven’t really come to the market with the non-guaranteed stuff lately,” he said.

Bonds backed by a government guarantee and issued by state-owned entities typically enjoy yields close to those of sovereign bonds. But in the case of troubled parastatals such as Eskom, its bond yields are about 100 basis points above sovereign bonds, with the 10-year bond yield being around 8.4 this week.

With Sanral’s shorter-dated debt, the credit risk is not seen as bad, but for longer-dated bonds the difference in yields are as much as 275 basis points higher than the government 10-year yield, Kerr said.

In June, Sanral announced a successful return to the market when it issued two government guaranteed bonds, allocating R600-million.

But critics believe the summonses are the last-ditch attempt of a roads agency under pressure.

Whatever the reason, it has presented an opportunity for Outa to challenge Sanral’s e-tolling system in the courts.

The 150 Outa members who have so far received summonses have unpaid toll bills ranging from just a few hundred rands to R8-million. The larger bills are for big transport companies.

“In the trucking industry, these guys are traversing these highways daily. And a lot of them are actually not able to travel on other routes,” Duvenage said, noting the organisation expected many more of its members to come forward with summonses.

He said the 60% discount on historical e-toll debt was the carrot and the summonses are the stick.