Students protest against NSFAS in March 2015.

Rising costs, like a tapeworm, gorge on the substance of universities, hollowing them from the inside out. Their appetite for income is insatiable, yet these higher education institutions are never adequately nourished.

It’s an affliction that universities around the world suffer, known as “cost disease”. But the malady is hitting South Africa’s institutions hard.

This week the #FeesMustFall movement — demanding more affordable, if not free, university education — has come to the fore again, as has the political anarchy that accompanies it.

The president has ordered no increases in tuition fees for the second consecutive financial year and treasury coffers appear too stretched to pick up the tab. While the fees commission whittles away at finding a solution, campuses have been plunged into disarray. On Wednesday, University of KwaZulu-Natal students torched vehicles and buildings and clashed with police. A law library was destroyed.

The downward spiral is quickening, with many universities claiming to be on the brink of — if not already in — crisis. Universities, which are run as not-for-profits, are pushing back against a fee freeze, unable to absorb the cost without an increase in state subsidies.

Ahmed Bawa, chief executive of Universities South Africa, said these institutions were pushed to the edge a long time ago. “That could mean very different things for Wits [the University of the Witwatersrand] versus the University of Zululand,” he said. “But I can say without any equivocation that a whole host of universities are at critical points.”

Jaco van Schoor, deputy vice-chancellor for finance at the University of Johannesburg (UJ), said, if there had ever been any slack on university balance sheets, it was all but gone by now. “The last two or three years have forced us to have a look at cost efficiency,” he said. “At university level we all cut our budgets.”

There is no credible research into the cost efficiency of universities in South Africa. Nico Cloete, the director of the Centre for Higher Education Trust, recently implored economists to conduct research into efficiencies at the universities.

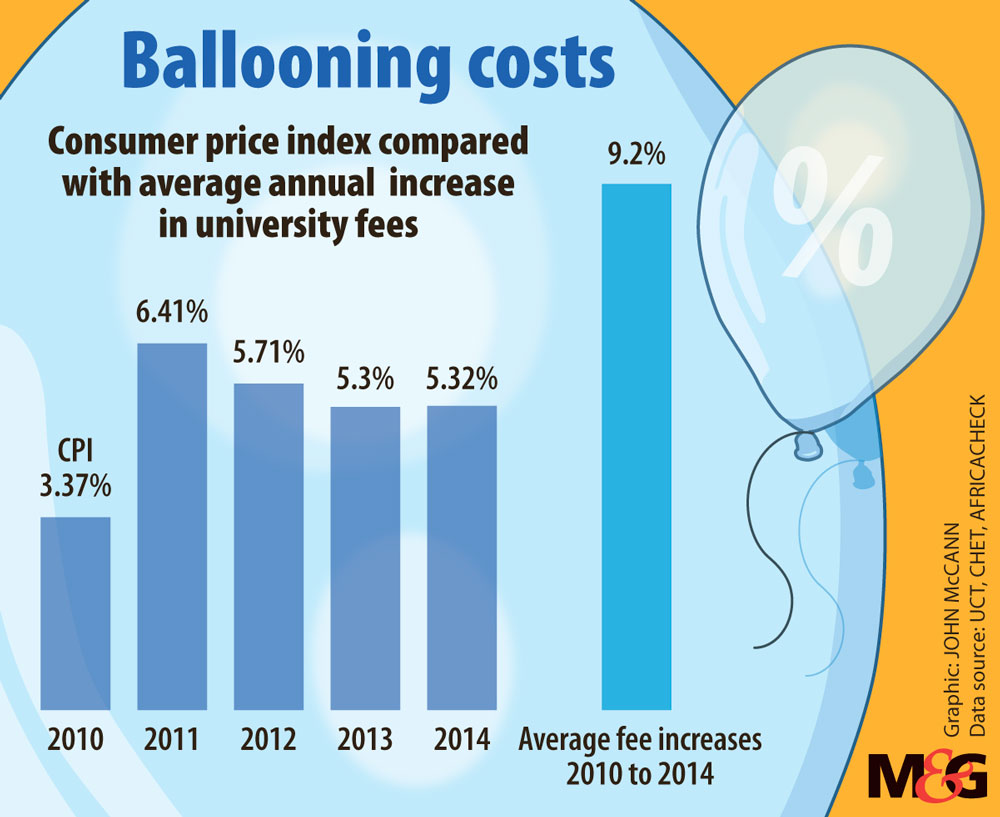

It is well known, however, that inflation at universities is typically higher than the national rate. In 2014, tertiary education fees grew by 10% whereas the national average inflation rate that year was 6.13%.

Universities point to a number of expenses, such as equipment and software, being denominated in foreign currencies and therefore rising as the rand weakens.

But a higher internal inflation rate is a common phenomenon found in universities worldwide. This is attributed to the rising cost of every university’s biggest expense — its staff. This was first labelled the “cost disease” in the 1960s and describes a phenomenon that sees salaries rise without a corresponding increase in labour productivity.

According to a 2008 report on tuition fees by Higher Education South Africa, now known as Universities South Africa: “In order to attract good staff, academics’ remuneration must keep pace with the remuneration of comparable occupations in the economy, which are largely determined by productivity changes in those sectors. But teaching and research are “labour-intensive” and not easily “mechanised” to increase productivity.

“As a result of the higher than inflation rise in the prices of higher education inputs … for universities to be able to continue to generate sufficient revenue (in real terms) from tuition fees, and be able to prosecute their mandates effectively, they have to raise tuition fees over and above the national inflation rate,” the report said.

Roy Marcus, the UJ council chairperson, said: “How effectively rands are used will vary from university to university, but the drive around this matter is ruthless.”

He noted the critical thing universities should be monitoring is the staff cost issue: “It is the biggest cost — no doubt.”

Staff costs account for anywhere between 50% and 75% of total expenses.

“We do have a small academic staff pool, and that means that costs do increase as there are supply and demand issues,” said Van Schoor.

Improved productivity requires investing more in academic staff than in administrators. But administrative staff at tertiary education institutions far outnumber academics, according to the higher education and training department’s statistics for 2014. Of almost 50 000 permanent employees, 18 200 (36.5%) were academic staff and 27 100 (54.4%) were administrative staff. The balance were service staff.

Meanwhile, the number of students per academic has steadily grown.

The only universities where academics outnumber administrators are at the universities of Venda, Limpopo and Sol Plaatje in the Northern Cape, which all have relatively small staff complements.

Bawa said the high number of admin staff were needed for accountability purposes. “Councils really require universities to be more rigorous in their reporting. And there are also big changes on how the auditor general audits the use of public money. All of this requires extra people.”

The expanding ranks of administrative staff are a concern for universities globally. In his 2011 book The Fall of the Faculty: The Rise of the All-Administrative University and Why It Matters, Benjamin Ginsberg warned that the growth in administrative staff had pushed up costs.

In 2014, the online news aggregator Huffington Post reported on a boom in higher education administrators in the United States. It quoted Richard Vedder of the Centre for College Affordability and Productivity: “They’ll say: ‘We’re making moves to cut costs,’ and mention something about energy-efficient light bulbs, and ignore the new assistant to the assistant to the associate vice-provost they just hired.”

One way the state and universities measure efficiency is by graduation rates. But only 30% of students graduate within three years and 56% in five years, according to a recent presentation by Cloete and researchers Charles Sheppard and François van Schalkwyk.

The real costs for students to be successful in South African universities are enormous, Van Schoor said. “[At UJ] we have a free inter-campus bus service and provide food to 3 800 students twice a day, and we don’t charge for it. It comes out of fees and subsidies.”

He estimated the socioeconomic costs local universities incur account for 10% to 20% of all expenses.

Said Van Schoor: “What does cost efficient mean? Can we apply that to the future of our country? It’s not like you are shopping at Pick n Pay and getting the cheapest tin of baked beans. To get a student from 18 to 23 is not a one-size-fits-all exercise.”