Pick 'n Pay employees on strike demonstrate outside the Gardens' store in Cape Town.

COMMENT

Though many will blame youthful exuberance for alienating potential allies, university students rampaged in central Cape Town after police using stun grenades forced them away from discussing the budget with Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan just before his parliamentary speech.

They were disheartened by his failure to come up with more than R5.7-billion in new funds after such intense social debate and student protest — and with such a legacy of underfunding universities by Gordhan’s predecessor, Trevor Manuel — and were infuriated by yet another heavy-handed police clampdown.

But they should not have been surprised. After all, Gordhan did signal divide-and-rule budget politics during a New York interview while on his last investor roadshow.

He said: “We have a solution which will meet the needs of the poor students, and the so-called missing middle as well, and it’s important that students who understand the calculations — who understand the trade-offs that we need between student fees being subsidised on the one hand and housing, welfare, health and other issues being paid for on the other hand — that they should be part of a constructive conversation.”

Across South Africa, #FeesMustFall had rejected that “solution” when it was proposed by Higher Education Minister Blade Nzimande two weeks earlier. They well understand that state subsidies provided 50% of university income in 2000, but steadily fell to 40% today, with students covering the bulk of the shortfall.

But they were again told by Gordhan to borrow more to pay for their education. The National Student Financial Aid Scheme’s extremely low repayment rates (R21-billion out of R24-billion in outstanding debt remains uncollected) reflects how that strategy is working.

Adding to household debt is usually only a short-term salve, as demonstrated by the ratio of borrowers who the National Credit Regulator deems “credit impaired” — still in the unsustainable region of 45%, barely lower than the 2008 high.

Redistributing funds from elsewhere in the budget, borrowing more (at the expense of alienating already cynical ratings agencies) and taxing rich people and South Africa’s highly profitable corporations are the solutions. In very small measures, Gordhan did all three.

But there is a reason the report of Nzimande’s 2012-2013 commission on fee-free education was covered up until its findings were leaked in 2015. His spokesperson, Khaye Nkwanyana, explained: “It is a public document but, due to the nature of the report, we decided not to make it public. Obviously we would have been setting the finance minister [Gordhan in 2013] up against the public if that decision and report was released.”

The choices Gordhan is making in this budget necessarily set him against the public. For example, his February 2016 budget provided a mere 3.5% nominal increase to foster care providers (who play a vital role, given the HIV orphan rate) and a 6.1% rise for the many millions of child support grant recipients. Although old-age pensions are not increasing, the extra R10 a month for child support grants — up to a token R360 a month — announced by Gordhan on Wednesday brings the grant’s overall increase this year to 7.5%.

But inflation for poor people is likely to exceed 10% because of a 15% rise in basic food costs, Eskom’s 9.4% electricity price increase and higher transport expenses. The poverty rate (for food and necessities) is now an excruciating 63%.

On social spending, South Africa has the fifth-lowest rate among the 40 largest economies (half that of Russia and Brazil) and still by far the worst inequality.

Instead of targeting social spending, Gordhan could instead have turned to the R233-billion annual overcharging in the treasury’s R500-billion plus procurement budget. His main accounting official, Kenneth Brown, acknowledges that “without adding a cent, the government can increase its output by 30% to 40%”.

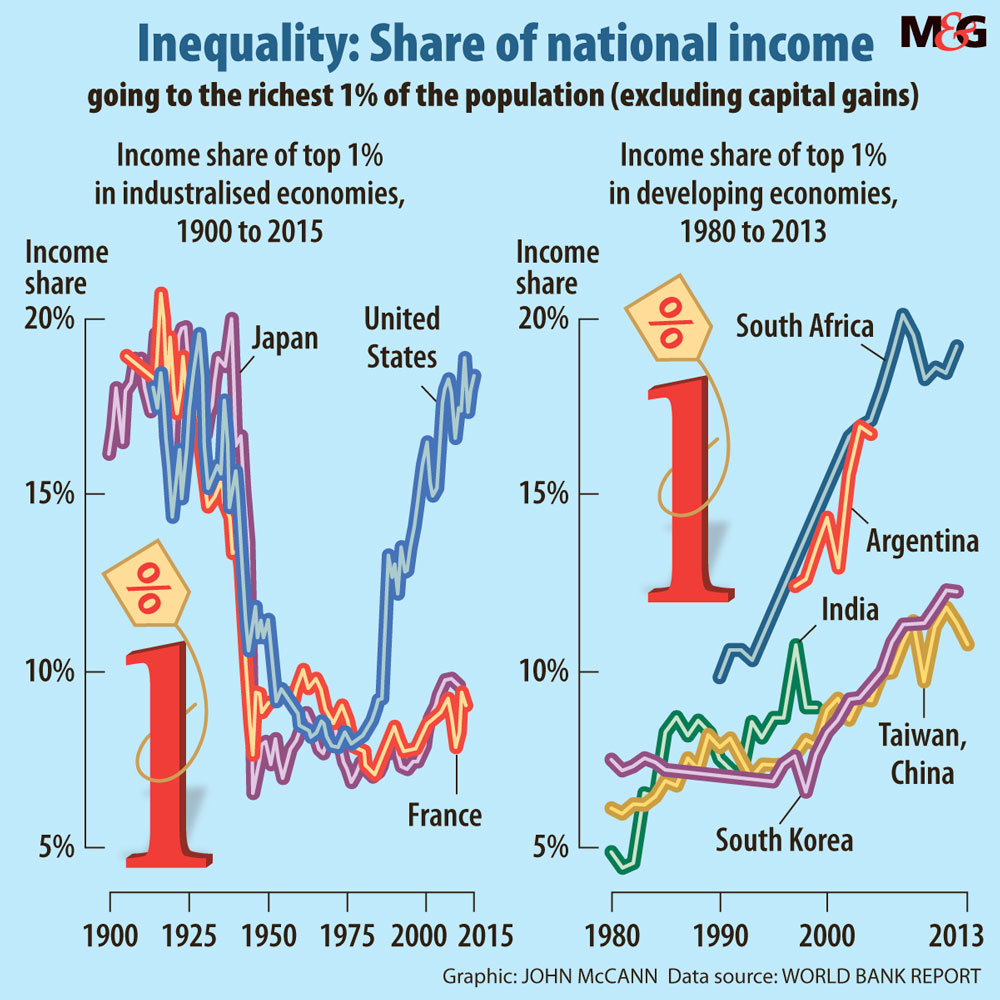

Some of those guilty of overcharging are also among those who normally cheer on treasury neoliberalism: rich people who have had an exceptional run since the early 1990s, according to a World Bank report released early this month. Post-apartheid economic policies raised the income share of the country’s richest 1% from 10% to 12% of total income (excluding capital gains) in 1990-1994 to 18% to 20% since 2009.

These are also the (mostly) men who take assets abroad illicitly. For, in addition to about R150-billion in net profit, dividend and interest payments that leave the country — the main cause of the current account deficit often reaching a dangerous 5% of gross domestic product — there is R300-billion in annual average illicit financial flows, as calculated by Global Financial Integrity.

These are the depravities that a strong, committed finance minister would attack to find the funding to offset society’s deprivations.

What rearrangement of forces is required to finally construct a democratic, developmental state? And, aside from the existing prolific protests by students, citizens and labour, what pressures can be mobilised from below to generate nonviolent regime change in the interests of a post-Zupta, post-neoliberal budget?