Pictures from the Wouter Basson exhibit.

Under Dr Wouter Basson’s supervision, Project Coast, apartheid South Africa’s chemical and biological warfare programme, mastered the idea of hiding things in plain sight. Fashioning tools of assassination masked as everyday objects, Project Coast’s arsenal included poisoned drinks, T-shirts and envelopes, and walking sticks capable of shooting poisoned pellets.

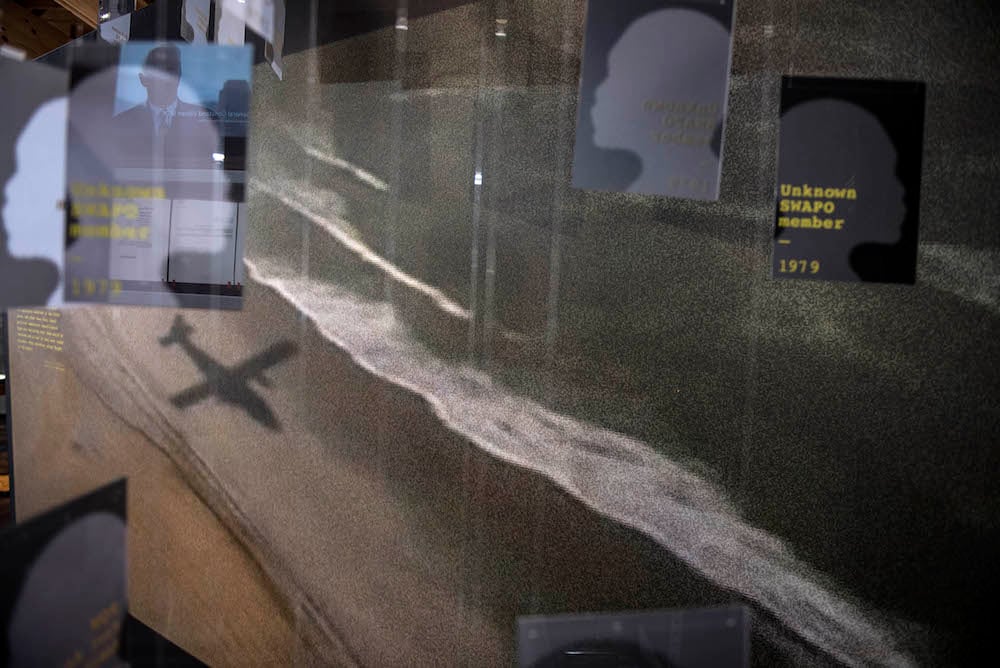

Poisoned Pasts: Legacies of the South African Chemical and Biological Programme, on show at the Nelson Mandela Foundation in Johannesburg, is an exhibition highly aware of the failure of words and language to encapsulate the scale and ghastliness of Project Coast.

Perhaps in acknowledgement of this, Kathryn Smith, one of its curators, states: “Poisoned Pasts is not an expansive exhibition, but it has been designed with a deliberate density and a nonlinear internal logic that does not seek to ‘choreograph connections’ or ‘overstate juxtapositions’.”

Project Coast, which was created to deal with the increasing threat of chemical warfare from South Africa’s cross-border enemies and how this could be studied and used domestically, operated on both a mass and a micro scale, and, as such, its mythology sometimes outweighs its established devastation.

By the early 1980s, about 200 members of the South West African People’s Organisation (Swapo) were poisoned with muscle relaxants and dumped in the Atlantic Ocean. In 1987, the notorious askari Joe Mamasela “recruited” 10 young men (between the ages of 15 and 22) “into the ANC”, only to lace their drinks and blow them up in the minibus taxi they were travelling in.

In between, attempts at poisoning ANC bigwigs such as Pallo Jordan and Ronnie Kasrils – between 1985 and 1988, Basson’s men tried twice but could not succeed in eliminating the two with poison – Basson’s antics were also concerned with maximum reach, involving his researchers into looking at putting birth control drugs in water supplies, the spraying of MDMA into protesting crowds to neutralise them and applying covert sterilisation methods through the dissemination of vaccines.

When the evidence of just how far Project Coast was made public during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission – former head of the military research laboratory Daan Goosen told the TRC that they were considering developing bacteria that would kill only black people – there was an overwhelming sense that Basson’s impact would be felt long after the TRC, with many people believing that Project Coast went as far as to influence the rapid spread of HIV in South Africa in the 1990s and beyond.

Here was a man who could play God successfully: kill us in our sleep one night and wake up to save some lives the next day, depending on his mood.

After the TRC, Basson went on trial to face 54 charges, ranging from the possession of drugs to conspiracy to murder. He was acquitted in 2002.

The Health Professionals Council of South Africa found him guilty of unethical conduct in 2013, but the process of finalising his penalty is still stuck in the appeals system, which Basson has made full use of.

Indeed, one can pore over the material of Poisoned Pasts for several days, stacked as it is with countless videos and voice recordings of Basson’s victims and the family members of those his operation brutalised.

There are also research papers and investigation findings of various purchases of poisons by members of Project Coast.

The documents, displayed in small, cubicle-like shelves, are not only limited to information on Project Coast, but also record the continuance of Dr Death’s – Basson’s nickname conferred on him by the media – public life and the outrage it generates.

In a letter to the editor published in the Cape Times in 2013, a reader, Shuaib Manjra, is appalled that “Dr Death” is invited to the Kelvin Grove Club to give a “motivational speech”.

He writes: “Diversity and freedom of expression do not extend to providing a platform for those associated with human rights violations.”

The display of this letter vindicates the curator’s logic that “deviations may throw up unexpected connections”.

Reading the letter, I was momentarily transported to the Franschhoek Literary Festival earlier this year and conversations that ensued over how the most decorated of apartheid’s killing machines should be accepted in public.

Although it may be easy to vilify the Dr Deaths and the Prime Evils (Prime Evil was the press’ nickname for apartheid police officer Eugene de Kock), how far does complicity extend? If one follows this logic, Swapo’s missing 200, represented graphically by anonymous silhouetted profiles suspended from above, are also the equivalent of the missing supporters of apartheid, hiding out in plain sight or, perhaps, seeking motivational words from Dr Wouter Basson.

Although I expected to be aghast at the sight of the gestation stages of a genocide and overwhelmed by the documentary evidence of what it takes to set it in motion, it is the photographs of Basson, smug and wincing from cigar smoke at a dinner table or goofing about in the back of a bakkie in Mozambique, that have me shaken and confounded. Because – surrounded by insurmountable evidence that lives were compromised, thrown out over the water, poisoned through food, beer and clothing, and set up for systematic wipe-outs – there are also, as former United States secretary of defence Donald Rumsfeld says, “unknown unknowns”.

To paraphrase him: Throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the “unknown unknowns” that tend to be a difficult category.

Looking into Basson’s carefree eyes while pondering Rumsfeld’s words, I am struck by the fact that I may never know what it truly means to be human.