Thousands of people at the epicentre of a man-made famine in South Sudan emerged from the safety of the swamps this past weekend hoping to receive emergency deliveries of food.

For months now Bol Mol, a former oil field security officer, has struggled to keep his family alive, spearfishing in rivers and marshes while his three wives gather water lilies for food.

They eat once a day if they are lucky, but at least in the swamps they are safe from marauding soldiers.

“Life here is useless,” Mol said as he waited with thousands of others beneath the baking-hot sun at Thonyor in Leer County.

Aid agencies have negotiated with the government and rebel forces to establish a registration centre in the village ahead of food deliveries.

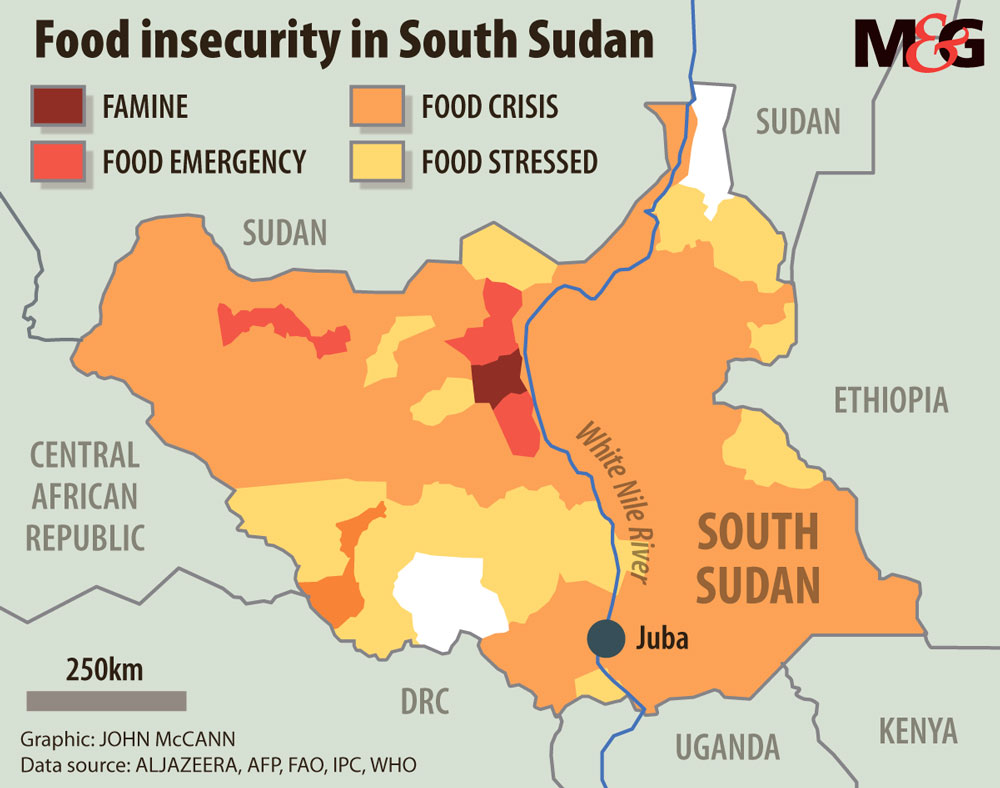

The United Nations declared a famine in parts of South Sudan a week ago. The hunger affecting about 100 000 people is not being caused by adverse climate conditions.

More than three years of conflict have disrupted farming, destroyed food stores and forced people to flee recurring attacks. Food shipments have been deliberately blocked and aid workers have been targeted.

It is no coincidence that soaring levels of malnutrition have been found in Leer, a rebel stronghold and the birthplace of opposition leader Riek Machar, whose falling-out with President Salva Kiir in December 2013 led to the civil war.

Evidence of the devastating conflict is everywhere: in the burnt walls of schools and clinics, in the ruins of razed homes and public buildings, and in the desolation of the once-thriving market.

A peace deal signed in August 2015 was never fully implemented. As recently as December the members of yet another 56 000 households were forced to flee to the safety of the swamps when yet another government offensive reached the area.

The constant need to escape the war means people are unable to plant or harvest crops, and their livestock is often looted by armed men.

With their livelihoods destroyed, people are gathering wild plants, hunting and waiting for emergency food supplies that come too rarely and are frequently inadequate.

“It is not enough,” Mol said as he waited to register for the next food delivery.

The fighting and the fleeing have interrupted all aspects of life: Mol said his children had not gone to school for the past three years.

“Right now the majority of the people are living in the swamps. If you go there and see the children you can even cry, the situation is too bad,” he said.

Nyangen Chuol, 30, keeps her five children alive with aid agency rations of sorghum supplemented with lilies, coconuts and sometimes fish.

“Before the conflict I lived here in Thonyor but had to move far away to the islands in the swamp for safety,” she said. This weekend’s registration for food deliveries had drawn her back.

Outside the famine’s epicentre in the northern Unity State, there are nearly five million people who also need food handouts, mostly in areas where the fighting has been fiercest.

“The biggest issue has been insecurity in some of these areas, which makes it very difficult to access,” said George Fominyen of the World Food Programme.

Aid workers warn that by the time a famine is declared it is too late, but the declaration has put pressure on the government to open up access, for now, and international aid agencies are intensifying their efforts.

Ray Ngwen Chek, a 32-year-old waiting for food, said the situation had steadily worsened over the years.

“Since 2013 we have planted no crops, nothing, we just stay like this. You don’t know what you will survive on tomorrow,” he said.

Hospitals and schools are shut, Chek said, and children, surrounded by conflict and with no other options, “are practising how to carry guns” instead of learning for the future.

Betrayed and neglected by the country’s leaders, the people of Leer struggle to hold on to hope for a political solution that would end the conflict.

But Chek is certain of one thing: “Fighting is not a solution.” — AFP