HISTORY

“The Germans ran away. Now we were having short magazine guns, we pushed them. They said we went 300 miles … [we were in the] 8th Army led by [British Field-Marshal Bernard] Montgomery. Those Germans never came back. We fought as one; black and white soldiers.” — Sergeant Petrus Dlamini speaking about the battle of El Alamein to filmmaker Vincent Moloi

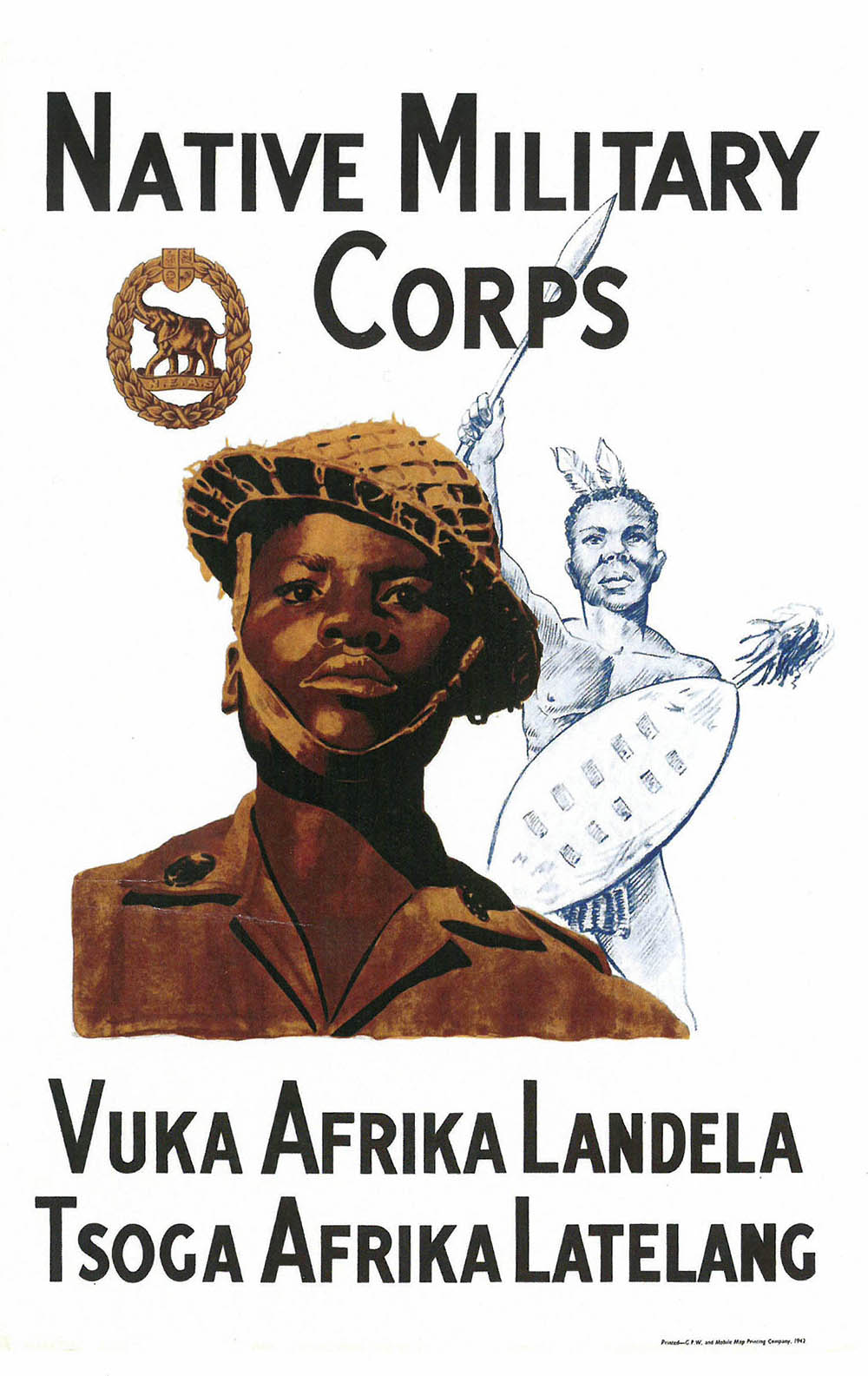

Most South Africans would be surprised by this statement. Official war histories largely ignored the contribution of black South African soldiers in World War??I and World War??II, and there is still widespread ignorance about the part they played, though attention is now being paid to the sinking of the SS Mendi in 1917. A few books now mention that black soldiers did vital and dangerous work, often under fire, but not that they were armed and fought in the two great battles at El Alamein, Egypt, in World War??II.

There’s a reason for this ignorance. The South African military’s propaganda department was given the task of downplaying the role of black soldiers. They did such a good job their myths still linger.

Military historian Dr Suryakanthie Chetty, in an essay on South African propaganda during World War II, said: “The Nationalists were vociferously opposed to black South Africans in the army at all, even unarmed.”

As prime minister Dr DF Malan said in Parliament: “To every Afrikaner, the use of black troops against Europeans is abhorrent.”

Chetty added that actions of black soldiers such as Job Maseko, who, while a prisoner of war, blew up a German supply ship in Tobruk harbour, “represented the possibilities of empowerment offered by military services that the state wanted to curtail”.

“Smuts could lose what support he had in Parliament” (if news of Maseko’s actions reached South Africa). Which is why , when Maseko’s commanding officer, a Colonel Sayer, suggested that Maseko’s name should be put forward for a Victoria Cross, his suggestion was vetoed. Maseko was awarded the less newsworthy Military Medal (MM) and news of his courageous and significant act of sabotage was contained.”

When asked about his 2007 documentary movie A Pair of Boots and a Bicycle, which celebrated the action of Maseko, film director Vincent Moloi said: “Our mothers and fathers were denied the opportunity to know their history.”

Returning soldiers told their families stories of wartime adventures, but how many soldiers of any race spoke of the horror?

In his book, The War of a Hundred Days: Springboks in Somalia and Abyssinia, 1940-41, James Ambrose Brown wrote what is possibly the only account of the terrible suffering of the South African troops, including units of black soldiers from the Native Military Corps, in the final triumphant battles they fought against Italy’s great military leaders, the Duke of Aosta and General Guglielmo Nasi, before Aosta surrendered.

My brother and I knew our father’s unit had stayed on in Abyssinia to help “mop up” the last remaining Italian regiments, and we knew that was where a young black driver saved his life. We were told of their adventures with wild animals but, we children, and perhaps our mother too, were told nothing of those appalling last days in Abyssinia. Many war stories stayed untold, and if stories were told by black South African soldiers, they were rarely recorded.

But, luckily, 60 years after World War II, Moloi interviewed black and coloured veterans about their wartime experiences. With persistent and penetrating questions he coaxed them to tell him the stories many had never spoken about before. From their recollections we know that, although black soldiers left South Africa armed only with assegais, “Up North” many were armed with guns. And we know they fought alongside white soldiers in the thick of battle.

Sergeant Petrus Dlamini spoke of being at Sidi Rezegh, Mersa Matru, Tripoli, Garowe in then Abyssinia and El Alamein before he went by boat to Italy with the South African 1st Division. He remembered doing guard duty in North Africa.

He says: “There, at Garowe, we were guarding as a sentry. We were guarding with assegai.”

The president of the ANC in the war years, Dr AB Xuma, said: “They are expected to fight aeroplanes, tanks and enemy artillery with knobkerries and assegais. What mockery.”

But just a few months later, Dlamini adds: “It was said — I heard a rumour — that the superiors [commanding officers] of South Africa, England and Australia said we must be given guns. Those guns were taken from the Italians in Kenya. They gave them to us and we were taught how to put ammunition and we were training with guns.

“Then we went to El Alamein and they took these [Italian] guns that were not right and they gave us short magazine Lee-Enfield .303. We got them at El Alamein.”

This has been verified in an article in the South African Historical Journal by historian LWF Grundling, who says: “Recruits received rifle musketry training, which was seriously handicapped by the defective Italian rifles with which they were issued.”

It was General Sir Pierre van Ryneveld who instructed the commanding officers in North Africa to arm black soldiers with Lee-Enfield rifles before El Alamein. But this does not seem to have been mentioned in dispatches.

Sergeant Dlamini said: “In the front line we were accompanied by whites. When we go to fight the Germans we were mixed.”

He spoke vividly of the battles he was in. Moloi recorded his description of the battle of El Alamein.

“It was like bees, those German planes together with our planes, the Royal Air Force and the South African Air Force. Many died there. Shots were like falling rain. They would hit here and here where you are sitting. When you are sleeping in your trench you would hear sounds of bombs all the time, when you wake up you would see those injured and those who are dead.”

Dlamini says they were with the 8th Army. “It [the 8th Army] pushed. Ai! Man! It was terrible, soldiers were lying dead, black and white, but the Germans were retreating and we kept following them. The Germans ran away. Now we were having short magazine guns. We pushed them. They said we went 300 miles … 8th Army led by Montgomery. Those Germans never came back. They went down together with the Italians you see.”

He added: “We were one. We fought as one; black and white soldiers. Here in South Africa (before we went up north) we were treated differently. Blacks were sleeping this side, whites on the other side. When we arrived in Egypt we mixed. If we made a queue, in front would be a white person, behind would be a black person then a white person. We were one.”

And, perhaps explaining why he had not spoken of his experiences before, he added: “You know the heart of a soldier. Your feelings die. You are always angry.”

Besides Moloi’s interviews with Dlamini, and with several other black World War II veterans, almost no records of the wartime experiences of black soldiers exist. And as it’s probably too late now to collect more, Moloi’s transcribed and translated interviews are a national treasure.

Marilyn Honikman is the author of There Should Have Been Five (Tafelberg) about the fall of Tobruk and the action of Job Maseko while he was a prisoner of war. When filmmaker Vincent Moloi and producer Eddie Wes heard Honikman was writing a book about Maseko they sent her the transcripts of Moloi’s interviews with black veterans. She uses their words in the book.