Unpopular: Security restrains a Greenpeace member protesting against the proposed nuclear build.

Once a pioneering nuclear energy giant, the Westinghouse Electric Company now finds itself filing for bankruptcy. This follows uncomfortably close on the heels of another nuclear industry leader, Areva, which was bailed out by the French government in January.

The financial troubles these nuclear powerhouses face is leaving the industry more than a little shaken and raises the question: Is the nuclear industry in meltdown?

“Nuclear industry is not in fine shape at the moment, certainly not in the Western world,” said Chris Yelland, an energy expert and the managing director of EE Publishers. “In the West, there have not been a lot of nuclear builds going on in the past two decades,” he said, adding that more nuclear plants are being decommissioned in the developed world than they are being commissioned.

In recent years Areva found itself in severe financial difficulty and this year was bailed out and acquired by the French government’s equivalent to Eskom, Électricité de France (EDF).

According to the 2016 World Nuclear Industry Status Report, Areva had accumulated $11-billion in losses over the past five years. The French government undertook a €5.6-billion bailout and broke up the company. The EDF itself is struggling with debt and last year took a 50% knock on its share price.

Last week, Westinghouse filed for a chapter 11, or “reorganisation”, bankruptcy, which typically suspends all judgments and other collection activities against the business while it reorganises its affairs, unlike a chapter 7 bankruptcy, according to which assets are liquidated to pay creditors. The chapter 11 filing also limits the effect on Japan’s Toshiba, which acquired the majority stake in the United States-based Westinghouse in 2006.

Westinghouse is already in a $6-billion hole, with more debt to come as two of its nuclear power plant projects are running three years behind schedule and are more than $1-billion over budget.

The key difference between the markets in which Westinghouse and Areva operate compared with other nuclear companies is that the two have to contend with a strong opposition to nuclear energy, said Kelvin Kemm, the chief executive of Nuclear Africa and chairperson of the South African Nuclear Energy Corporation. He also cited the influence and effect former US president Barack Obama had in putting the brakes on nuclear energy in the US.

According to the 2016 nuclear status report, eight early closure decisions were taken – in Japan, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan and the US, and California and Taiwan have made announcements about phasing out nuclear power. In nine of the 14 countries building nuclear plants all projects are running behind schedule, mostly by several years.

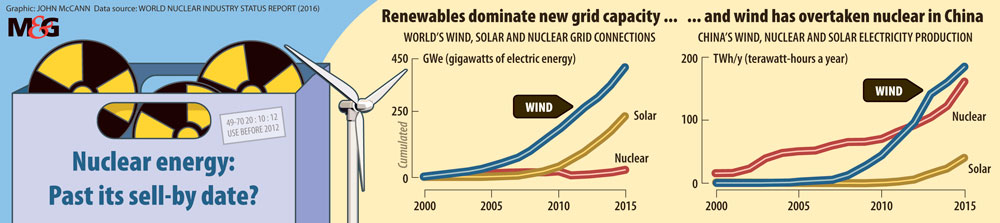

Despite this apparent downturn in the developed world, globally nuclear power generation increased by 1.3%, “entirely due to a 31% increase in China”, the report said.

Ten reactors started up in 2015 – more than in any other year since 1990 – eight of which were in China. Construction on them started before the Fukushima disaster.

But the number of units under construction is declining for the third year in a row, from 67 reactors at the end of 2013 to 58 by mid-2016, 21 of which are in China, according to the report.

In 2015, construction began on eight, six of which were in China. But this was down from 15 in 2010, 10 of which were in China. That country spent more than $100-billion on renewables in 2015, and investment decisions for six nuclear reactors amounted to a much lower $18-billion.

But the fall of a nuclear giant such as Westinghouse would have little impact on South Africa’s nuclear ambitions – “I don’t see it affecting us at all,” said Kemm.

“It is not as if, if Westinghouse did collapse, all nuclear technology would go with it,” he said, adding that the Chinese are already building an upgraded version of Westinghouse’s AP1000 nuclear reactor, in collaboration with Westinghouse itself.

Yelland agreed: “For South Africa’s nuclear build it means little – the real players in the South African nuclear game are, in any event, the Russians, Chinese and Koreans,” he said.

“The Russians are seriously ahead of the pack. They are at the forefront of this thing and doing a lot of work globally,” said Yelland. “The Chinese are not doing a lot globally. They are doing a lot locally” – where they do not have the same labour, political or financial restraints as they would elsewhere.

Reactors are designed for a 60-year lifespan and this can usually be extended to reach 80 years.

Kemm said the technology of the various players are of a similar standard. South Africa’s controversial nuclear tender would ultimately be awarded based on the vendor’s ability to cater for other requirements, including localisation.

“It’s a marriage. It’s very much about the business partnership we are looking at,” Kemm said.