More energy hits the semiarid earth in the Northern Cape than in most other places on Earth.

Another June 16 Youth Day has come and gone. As typically happens at this time, various political leaders, and newspaper editorials, bemoaned the lack of employment for young people, emphasising the need for more job opportunities.

In his National Youth Day address in Ventersdorp for instance President Jacob Zuma acknowledged that the economy is affected by ‘sluggish growth’. But, he said, “a growing economy is our most potent solution against youth unemployment” and that government “will be meeting with business” to advance this.

Any serious initiative to create jobs and strengthen the economy is to be welcomed. But structural youth unemployment will be part of our reality for many years. The idea that it can in any way be ‘solved’ in the foreseeable future must be recognised as pure fiction.

This points to the need for new ways of thinking about, and new institutions that are concerned with the status and position of young unemployed people. In engaging with these issues, the potential role of key components of the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) should be a central focus.

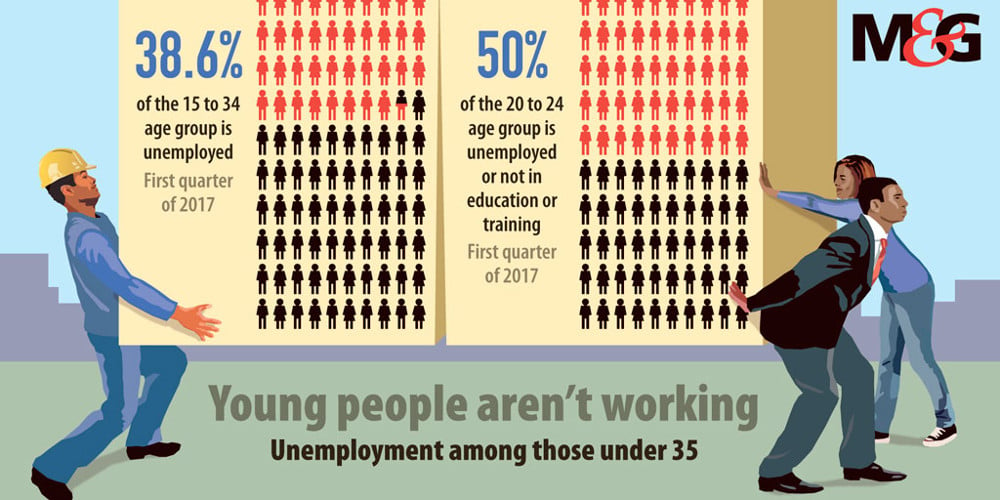

According to the Stats SA Labour Force survey for the first quarter of 2017, 38.6% of those in the 15-34 year age category are unemployed. But this figure excludes many others who are discouraged from seeking work and are not counted in unemployment statistics. A full 50% of those in the 20-24 year age category are neither in employment nor in education or training.

If the percentage of the working age population who are employed (the labour absorption rate) is used as a measure, employment is still lower (43.7%) than it was in the equivalent period prior to the onset of the 2008 recession.

Even if the rate of economic growth were to improve, chronic structural employment will remain for a considerable time. The 2012 National Development Plan for instance identifies various challenges to economic growth in South Africa, including the declining role of manufacturing as an employment provider in both middle and high income countries.

However, information technology in its various permutations has, and will continue to lead to many types of jobs becoming redundant, not only in the manufacturing sector. It is no longer simply blue collar work that is under threat from the advance of technology. Even tertiary education no longer provides the certainty of stable employment.

Many South Africans face a perpetual search for work that, when they find it, will often be poorly paid and temporary. The main alternatives will be ongoing dependence on other family members (who may be in a similar predicament), poorly paid informal work, or crime. Financial independence and stability are likely to lie continually beyond the reach of many.

The fact that many young people face long term economic insecurity needs to be brought into focus. This is a reality that cannot be wished away and that needs to be confronted alongside those measures that can be taken to improve economic growth or job creation.

These issues highlight the significance of various components of the EPWP, which is coordinated by the Department of Public Works. While often portrayed as short-term, there are now a number of EPWP programmes that provide work on a medium- to long-term basis.

The most prominent of these is the Community Work Programme (CWP) which provides two days of work per week, up to 100 days per year, to unemployed and underemployed people. Currently it is operational at roughly 200 sites spread throughout South Africa, providing work to upwards of 220 000 people on an annual basis. Participants must be residents of the area where the site is, and the work contributes to public goods and services that are prioritised by the community.

Another example is the Zibambele programme, currently including nearly 100 000 households, each of which has responsibility for basic maintenance of a 750m to 1km stretch of neighbouring rural road.

These programmes provide a safety net to unemployed people by ensuring that they have access to a regular number of days of paid work per month. The stable, though small, incomes that they receive may be their sole income or supplement other income earning strategies. Because they involve participants in work in the areas in which they live, as well as because of the services provided to fellow residents, they also enable participants to feel that they are worthy members of their communities.

The hope is that these programmes will enhance employability. Some participants are able to exit these programmes to take up other opportunities. However in areas in which these programmes operate opportunities may be few, and many participants remain for an extended period.

In addition to enhancing the social inclusion of the most marginalised South Africans, these programmes have a much broader significance. They are also new and innovative institutions that engage with the question of how to give structure, meaning and dignity to the lives of those caught in the limbo of ongoing unemployment. They are also potentially significant as violence prevention initiative. In the South African context of high inequality, chronic unemployment and poverty are undoubtedly contributing factors to high levels of violence.

However one of the issues that these programmes need to engage with is the ambivalent attitude of many young people, and especially young men, towards them. Research by the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR) shows that young men often dismiss the CWP on the basis that it falls short of their expectations, despite the absence of other more viable options. Beyond the limited income, most of these opportunities also have little appeal in terms of status or avenues for personal and career growth.

Rather than being short-term interventions these types of programmes are likely to have an ongoing role to play in in South Africa. But it will be necessary to find new ways of thinking about, organising and presenting these programmes if they are to become more significant in addressing the position of young people faced with structural unemployment.

This article is written on behalf of the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation. Bruce is a freelance researcher