Farmers are responsible for approximately 30% of the Western Cape water usage

NEWS ANALYSIS

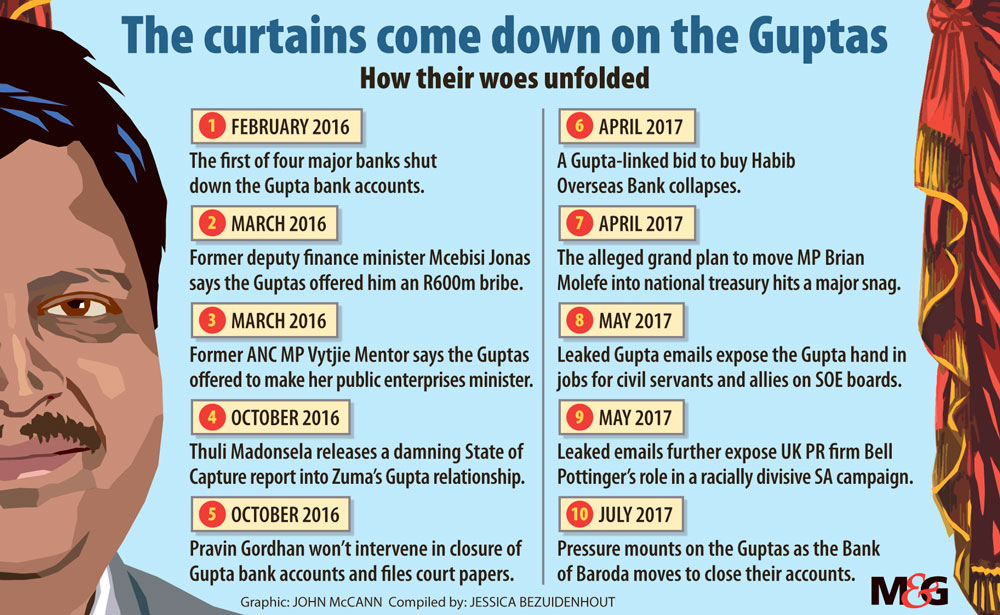

The cash may be in Dubai but back home the Gupta network is bleeding amid a multipronged legal, political and financial campaign fighting back against state capture.

The Bank of Baroda may finally have plucked up the courage to say hasta la vista, Trillian Capital Partners has cut Salim Essa loose, and at Megawatt Park Anoj Singh was left to hold a lone vigil over the remnants of what was once the family’s cash cow, Eskom. Singh was placed on special leave on Thursday pending a forensic investigation.

Of course, the country’s unofficial first family has deep pockets and has proven to be rather adept at comebacks. But it seems South Africa is in for an awesome August.

President Jacob Zuma faces a parliamentary vote of no confidence on August 8, and the Eskom hearings would see some bigwigs, and perhaps even the Guptas, line up for a grilling in Parliament. And, across the ocean, Bell Pottinger will have to face the music at an August 18 hearing of the United Kingdom’s industry watchdog body after being exposed for sowing racial division in South Africa.

South Africans have connected the dots, and it has become clear that a joint venture with the Guptas or any of their associated companies is a reputational nightmare even for the greedy among us.

It was always intriguing how the Gupta network functioned – a string of companies forming the top layer of an empire spanning mining, media and, as it now turns out, consultancy and recruitment.

Below that were several proxy companies that would bill and cross-invoice each other in transactions that baffled investigators and apparently escaped auditors such as KPMG.

For years, some members of the family ordered senior government officials and parastatal bosses to their Saxonwold compound to dish out orders. Those who played ball were promoted – albeit with a Gupta-style noose around their neck.

“We will make you mining minister and you will give us Optimum Coal”; “Handle our immigration hassles and you’ll get a job in Delhi”; or even better: “We give you a diplomatic post when you get into trouble for allowing us to land our plane of wedding guests at a national key point.”

The ones who squealed were handled – ask Vuyisile Kona, the former chief executive of SAA who was shunted into the wilderness after he dared to blab about an alleged R500 000 bribe as far back as 2013.

Back then nobody dared to go up against the Guptas – certainly not publicly.

The family rejected Kona’s claim at the time, but questions must be asked now that there are some extra dots to connect in the form of former deputy finance minister Mcebisi Jonas’ even bigger bribe claim.

Just as Gupta fatigue set in, thousands of leaked internal emails emerged and provided further information to shore up the long-held belief that the Guptas were running a parallel government in South Africa.

The #GuptaLeaks emails showed how Gupta companies or those in their network had cashed in on multibillion-rand deals across state-owned enterprises including Transnet and Eskom.

They also exposed how the Free State provincial government had funded a dairy operation to support black farmers, only for that money to be diverted through a complex international company structure to pay for the ostentatious Sun City wedding of Vega Gupta four years ago.

But as the Twitter hashtag #CountryDuty encouraged citizens to fight back, the Guptas’ friends in high places started falling. Brian Molefe and Matshele Koko are but two executives who have had humbling episodes and must be ruing the day they signed up for #GuptaDuty.

So too must multinationals such as McKinsey & Company and SAP, as well as another German software company, all of which have now been exposed for allegedly striking lucrative deals with government entities that ended up lining the coffers of the Gupta network.

This week saw the demise of another partnership as Trillian Capital Partners announced that Gupta lieutenant Salim Essa has sold his stake in the company for an undisclosed amount.

Trillian has maintained it has no links to the Guptas, but one of its former chief executives punched holes in this claim last October. She told then public protector Thuli Madonsela that executives at the company had prior knowledge that Zuma would fire former finance minister Nhlanhla Nene and had planned to cash in on that inteligence.

Nothing was sacrosanct. The Gupta network’s tentacles spread deep into the South African system of government, enabled by its access to the president’s family – including the pampered prince Duduzane Zuma, who now owns a mansion in Dubai, drives luxury sports cars and flies business class around the world courtesy of his Gupta relations.

Even rank-and-file civil servants did not escape the tentacles’ reach. This week it was the turn of Public Enterprises Minister Lynne Brown’s personal assistant, Kim Davids, who was exposed for a “holiday” in Dubai that coincided wonderfully with emailed instructions for a chauffeur pickup to the Gupta mansion. (Best to ride out this initial storm, Ms Davids; there are more emails coming.)

For now, the Guptas’ immediate headache is the Bank of Baroda’s threat to close its accounts.

The South African Reserve Bank has confirmed that its supervision department is “looking into” a complaint brought against the Bank of Baroda by the Organisation Undoing Tax Abuse (Outa).

The bank, seemingly the last channel through which the Guptas and their associates could move money locally wants to close down the family’s accounts by the end of August, Business Day reported on Thursday.

Research done by Outa suggests that the bank is owed almost R1-billion in loans granted to the Guptas or associated entities on a host of properties. This is despite the purchase prices on the properties amounting to around R250-million. Baroda’s South African arm appeared “massively exposed,” said Ben Theron, Outa’s chief operations officer.

The list of bonds ostensibly granted to the Guptas, and published by Outa, is peppered with apparent anomalies. They include a R280-million bond on a farm with a purchase price of R2.2-million, whereas the current estimated value of the land is a mere R330 000.

The Reserve Bank has kept shtum, saying it does not comment on specific banks. But under the Banks Act it has the power to cancel or suspend the Bank of Baroda’s authorisation to operate in South Africa.

It is unclear whether Baroda headquarters in India is aware of the dilemma the accounts present, and whether it has the appetite to square up against an angry South Africa. Neither the Guptas nor Baroda’s Johannesburg office responded to questions.