Turn for the worse: Men gather at Lonmin’s support centre in Marikana hoping to hear they have been chosen to work. The agriculture

The news that Jacob Zuma survived another vote of no confidence was not the worst news of the week. The worst news was arguably the unemployment data.

It reinforces the extent to which the economy is limping along and many South Africans are eking out a living.

The data reveals not only the stubbornly high level of unemployment but also the extent to which there is a mismatch in the skills of the labour force and the skills needed in the sectors that are creating jobs.

With about 3.3-million young people between the ages of 15 and 24 not in active employment, according to Statistics South Africa, nor in an education or training programme of some kind, the situation has been described as verging on a ticking time bomb.

These problems notwithstanding, economists argue that South Africa can overcome this impasse if the right policies are put in place and the current cycle of political uncertainty comes to an end.

The quarterly labour force survey showed that the unemployment rate remained stuck at 27.7% in the second quarter of the year, not budging from the previous three months. This record level was up from 26.6% during the same period in 2016.

A closer examination of the report by StatsSA reveals more worrying trends in unemployment, which are set against a backdrop of thousands of job cuts by major firms in recent weeks.

When accounting for discouraged work seekers — or what is known as the expanded definition of employment — the unemployment rate is closer to 36.6%, up 0.2 percentage points from the previous quarter. This figure accounts for the people of working age who have stopped actively looking for jobs.

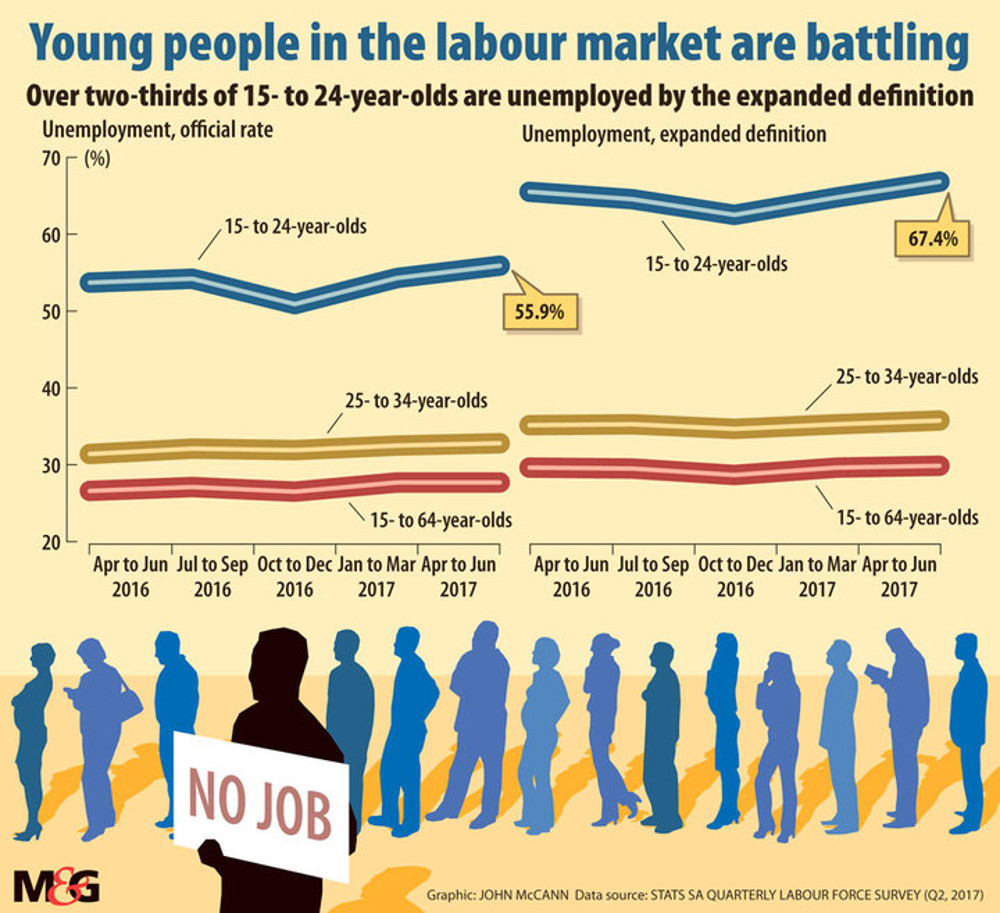

Young people in the labour market in particular are having a difficult time. The unemployment rate for those aged 15 to 24 years was at 56% for the second quarter this year. Year on year, the figure was up from 53.7%.

Using the expanded definition of unemployment, the rate for this age group is 67.4%. For young people aged 25 to 34, the unemployment rate was almost 33%, which also increased from the previous year.

Overall the country’s absorption rate, or the employment to population ratio, shrank to 43.3%.

According to Peter Buwembo, the chief director for labour statistics at StatsSA, the absorption rate measures the extent to which the working-age population — or those between 15 and 64 — is employed.

“The absorption rate tells us that only 43.3% of those who are in the working age have jobs,” he said. Before the 2008-2009 recession, the figure was 45.8% and to date the South African economy has failed to return to that figure, Buwembo said.

“The question we keep asking ourselves is: Will the country meet the [National Development Plan] target of raising the absorption rate to 61% by 2030?” he said.

For young people, the absorption rate is even lower — at 12% for 15- to 24-year-olds. To add to the problem, according to StatsSA, a large part of this age group, roughly 32.2%, are not actively employed nor are they in some form of education and training programme.

“This is approximately 3.3-million young people aged 15 [to] 24 who are idle,” StatsSA said when the survey was released.

The survey also reveals the extent to which education is a factor in employment. The unemployment rate among graduates was 7.4% for the second quarter of 2017. For people with some form of other tertiary qualification the rate was 17%.

For people with a matric or less than a matric, the unemployment rates were almost 28% and 33% respectively.

“This points to the fact that we are just not getting education right for the majority of people,” said Azar Jammine, the chief economist of Econometrix. “They stay sidelined and marginalised, and the handful of people who can afford to get a decent education get the jobs and keep the economy going.”

According to the survey, job losses in the second quarter were driven by declines in six out of 10 industries. The greatest number of jobs lost were in construction, agriculture and mining.

Employment gains were made in sectors such as trade and finance, but these were not enough to outweigh the losses in others.

The unemployment rate is likely to get even worse in light of a spate of retrenchments announced by a number of large companies in recent weeks. This includes Pick n Pay, which recently announced it had cut 3 500 jobs by offering staff voluntary severance packages.

A number of mining houses have recently also announced retrenchments, adding to what the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) has said is the loss of about 80 000 jobs in the sector over the past five years.

Sibanye Gold announced last week that it is planning to retrench about 7 400 permanent employees at its Beatrix West and Cooke operations.

AngloGold Ashanti also recently announced it would be restructuring its South African operations, with 8 500 jobs likely to be affected.

In the relationship between employment and economic growth, employment is a lagging indicator, said Christie Viljoen, an economist for the advisory firm KPMG.

The short-term outlook for unemployment is that it will remain at a high level, he said, and will only be erased by a meaningful pick-up in economic growth.

Maarten Ackerman, the chief economist of Citadel, a wealth management firm, said the past quarter’s results were not unexpected. But arguably what is of greater concern is the inability of economic growth to keep pace with population growth in recent years.

This implies that the economy is unable to create a sufficient number of jobs to satisfy the increasing workforce, he said — and this is without considering the question of whether the economy is creating the right kind of jobs to absorb the labour force, or whether workers are being provided with the right skills, he said.

“In reality, it is almost like a ticking time bomb. You have an increasing labour force and an education system that is giving you a largely uneducated labour force.”

South Africa needs to “reindustrialise” and create jobs in sectors such as mining, manufacturing, agriculture and construction, which could accommodate the existing labour force, Ackerman said.

Over time, an improvement in the education system could see improved skills across the labour force and ensure that more people could graduate into the services sectors, he said.

Despite the concerns over deindustrialisation, Ackerman said the country had all the right ingredients to reverse this. It has access to commodities, it has the people and it has deep and liquid capital markets.

“The missing link is all about the right policy to ensure South Africa becomes more efficient and productive.”

This includes greater labour flexibility, which does not mean eradicating trade unions or not implementing a minimum wage. He said it is about being able to hire and fire people without as much red tape to enable companies to adjust dynamically to changes.

The state also needs to provide more incentives to business to encourage direct investment, although most of the government’s funds are going into current expenditure, such as the wage bill, limiting the incentives it could provide to businesses.

As long as current policy and political uncertainty prevail, the long-term structural issues relating to both economic growth and unemployment will not be resolved, Ackerman said.

Investor confidence will return only once there is more policy certainty, including certainty over matters such as the independence of entities such as the Reserve Bank and the treasury, he said.