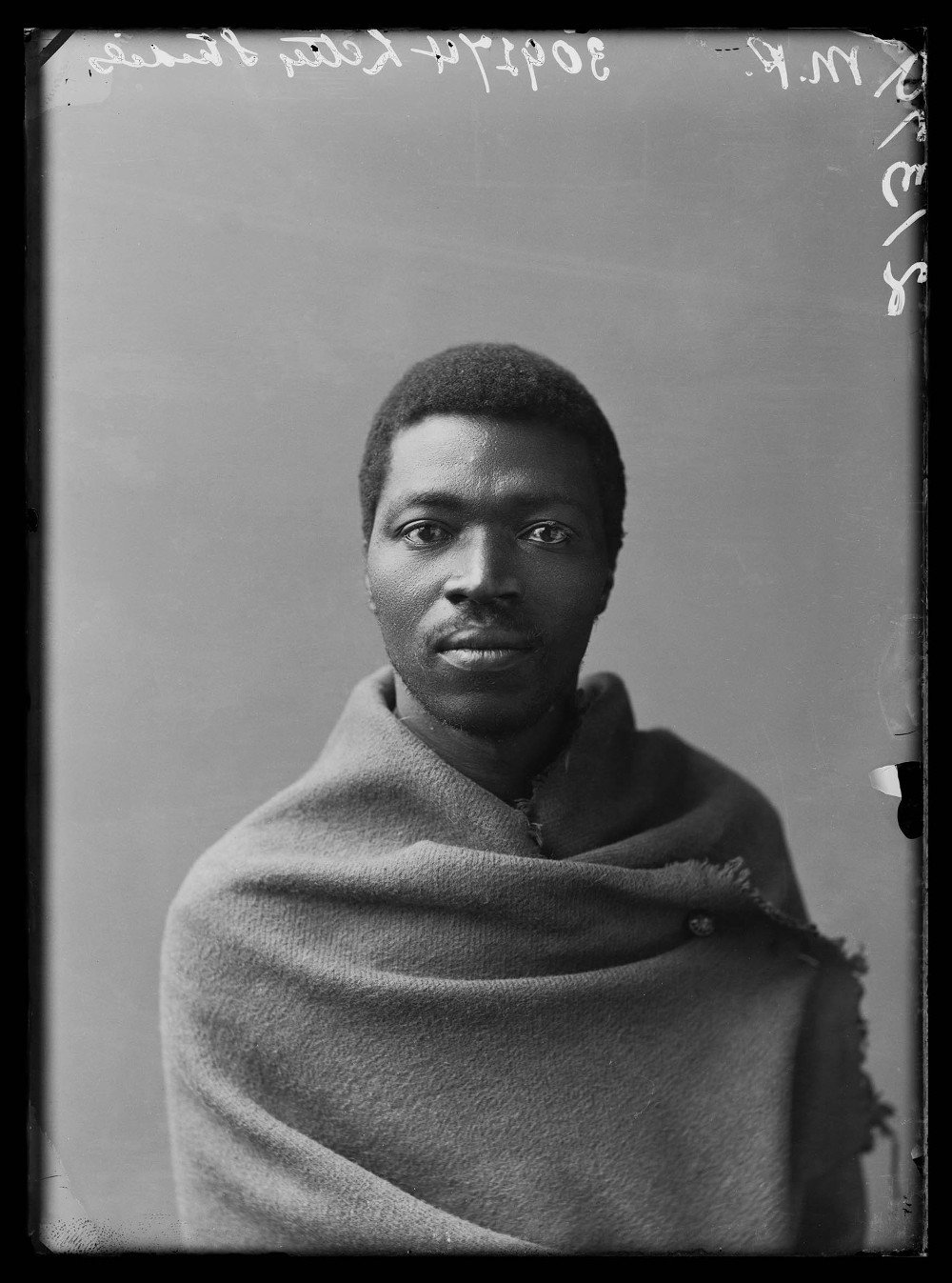

The 126-year-old pictures are a record of the tour to Europe by the African Choir. Members of the African Choir

A huge crowd has turned out for the opening night of the African Choir 1891 Re-Imagined exhibition at Iziko National Gallery, presented by the gallery in conjunction with the University of the Western Cape’s Centre for Humanities Research (CHR).

It is the night before Women’s Day and, a short way down the road, the protest eisteddfod (as my friend Pam calls it) is in full swing outside the houses of Parliament, while votes for the eighth vote of no confidence in the country’s president are being counted.

Inside Iziko, however, we can hardly hear igwijo lomzabalazo as we eagerly await the end of the speeches. We want to hear the music.

Although it includes photography, the main element of this exhibition is the musical interpretation of the songs that the African choir performed on their tour, composed by Philip Miller and Thutuka Sibisi who worked from a surviving programme from 1891 and not the original music.

“Even though in the 1890s there were wax recordings of music, none were made of ‘The Choir’, so there is no correct way of hearing them,” says Miller about the “re-imagined” part of the exhibition.

“I’ll be the judge of that,” I think to myself, as I wonder which tracks they might have chosen from the canon of Xhosa hymns that the Jubilee Chorus — “the African Choir” or “the African Native Choir” — is said to have performed during their two-year tour of the British Isles.

When the speeches are finally concluded and we enter the hall in which the exhibition is housed, I quickly scan the track list for the recording and I see “Ulo Thixo Omkhulu” printed on the wall. My heart soars and sinks almost simultaneously as I spot the spelling error in the prefix.

John Knox Bokwe’s composition, UnoThixo Omkhulu, is one of my favourites even though I no longer consider myself religious or Christian. It’s one of those wonderfully layered sonic a cappella soundscapes that is typical of Xhosa choral compositions made when musical instruments were hard to come by and composers improvised with voices.

“Aaaahh-haaaa-hooooom-na ah-hom-hom-na”, I sing under my breath, my baritone ever ready to go as low as I need to. Nope, they have done something different to it. I wait for the line: “unoThixo omkhulu/ osezulwini/ ongoyenayena/ ikhakha lenyaniso”, but it never comes. Oh well, they did say “re-imagined”. But couldn’t they fix the spelling on the track list?

Understandably, in archival records that is how the title of the composition is written, but anyone can see it’s an obvious typo. Such typos are almost characteristic of all Xhosa transcriptions of the time and the decades after.

“Ewe, le nto kakde yinto yaloo nto./ Thina, nto zaziyo, asothukanga nto” (sic?) acknowledges famed poet Samuel Edward Krune Mqhayi in the opening line of his 1943 poem, Uku-tshona kukaMendi (The Sinking of the Mendi). For 70 years, no one has ever thought to correct “kakde” to “kakade” and it is still reprinted like that to this day.

But Sibisi was right in his speech, the singers on the recording give their all and it is glorious, a sonic perfection that is almost equally matched by the reproduction of these 126-year-old portraits, now blown up to a larger-than-life size. At this scale, they reveal a mischievous mirth behind the eyes of 18-year-old Charlotte Mannya that I had not noticed before.

The images first received worldwide attention as a result of an article in The Guardian on pictures of Victorian-era black people, which went viral and intrigued us all. The selection at Iziko, however, is limited only to a handful of individual portraits of the singers. Handsome men draped simply in the light blankets of the style typical of the Xhosa of the time, some in full peacock mode with elaborate headgear and strings of beads adorning their faces. Beautiful women with slightly less elaborate accessories, looking as though to the manner born.

“[Mrs Eleanor Xiniwe] is a young lady-like, native woman, the regularity of whose features despite her sable complexion, vies with most European faces, and who has dignified and rather stately manners,” proclaimed The Illustrated London News of August 29 1891 in a caption accompanying a portrait of Xiniwe at the time.

[London Stereoscopic Company/Hulton Archive/Getty Images]

Renée Mussai, curator and head of archive at Autograph ABP, informs us in her speech that the images were discovered in the vast Hulton Archive — the rest of the physical collection of the images is in the Getty Images collection.

Missing from the Iziko selection are the group photographs, which include the promoters Walter Lety and James Balmer, who also served as the choir’s musical director on the tour. Also missing are the photographs of the singers in traditional Victorian dress.

The choir arrived in London sometime during the northern summer of 1891, ostensibly to raise funds for a new technical school to be built in Kimberley and to alleviate the plight of mineworkers on the diamond mines. The money was raised not only by giving performances but also by giving public talks on life in South Africa, which fascinated members of Victorian society no end — and which earned speakers like Mannya and Xiniwe a guinea each time they were asked to speak.

According to Margaret McCord, the daughter of Dr James McCord, who was Charlotte Maxeke’s (née Mannya) employer, within four days of their arrival, they performed at the Crystal Palace as part of the last public celebration of Queen Victoria’s jubilee. They were then invited to deliver a command performance for Queen Victoria at her summer residence in Osborne, on the Isle of Wight, which took place on the night of July 24 1891.

“Do you know they were eventually abandoned?” says Dr Premesh Lalu, the director of the CHR,as we make our way through the exhibition.

By the end of 1891, things had begun to go a bit south for the choir. Accusations of embezzlement were levelled against the promoters by the choir leader, Mr Paul Xiniwe, who eventually left the choir and returned to South Africa in 1892. Mannya and Eleanor Xiniwe were involved in a physical fight at the restaurant of the Trevelyan Hotel. Paul Xiniwe was also accused of having an affair with a younger member of the choir, Sannie Koofman, who later gave birth to a stillborn baby. She is alleged to have hidden the baby in a trunk and, when it was discovered, was imprisoned for “concealment of birth”.

[London Stereoscopic Company/Hulton Archive/Getty Images]

Lety and Balmer eventually abandoned the choir in late 1892, but not before taking Mannya and a few of the original members on a tour of the United States.

In the US, Mannya made the acquaintance of members of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church. Later, after returning from the ill-fated tour of the British Isles, she assembled her own choir and embarked on a tour of the US, where she had hoped to raise funds for the furtherance of her own education.

Bishop Henry McNeil Turner of the AME organised a scholarship for her and she enrolled at Wilberforce University, where she earned a BSc degree, becoming the first African woman to do so.

It was at Wilberforce that she also met Marshall Maxeke, who arrived at the university in 1896, and would become her husband.

Even in those early Jubilee Choir days, there is evidence within Mannya of the political fervour that would come to characterise the iconic Charlotte Maxeke.

In September 1891, she was interviewed by a journalist, William Stead, to whom she is quoted by Jane Collins as having said: “Let us be in Africa even as you are in England … Help us to found the schools for which we pray, where our people could learn to labour, to build; to acquire your skill with their hands.”

Indeed, she is said to have used her time in Britain to shine a light on the plight of black South Africans and the encroaching Afrikaner domination that would eventually lead to the second South African War.

After her return from Wilberforce, she and her husband became active in the discussions and work of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC), which would later become the ANC. Although women were initially not allowed to join the SANNC, her experience in Britain attending suffragette meetings is said to have been instrumental in keeping her focus on the “woman question”, which she wrote about in Umteteleli wa Bantu. In 1918, she formed the SANNC Women’s League.

There’s something about the smirk that seems to lie just under the surface of Charlotte Mannya’s otherwise powerfully still demeanour in her portrait at the Iziko Gallery. It’s almost as though she is thinking: “You think I’m only here to be a good black and just sing for you, but in truth I am here to disrupt and dismantle — or at least die trying.”

Ewe, le nto kakade yinto yalonto.