The state-owned Zimbabwe Consolidated Diamond Company has cordoned off the Marange area. The plight of villagers has worsened under its watch. Water is polluted

Just over a decade ago, Zimbabwe discovered one of the world’s richest diamond deposits in an area known now as the Marange diamond fields. This find was supposed to transform the country’s economic prospects and, ultimately, the lives of its people.

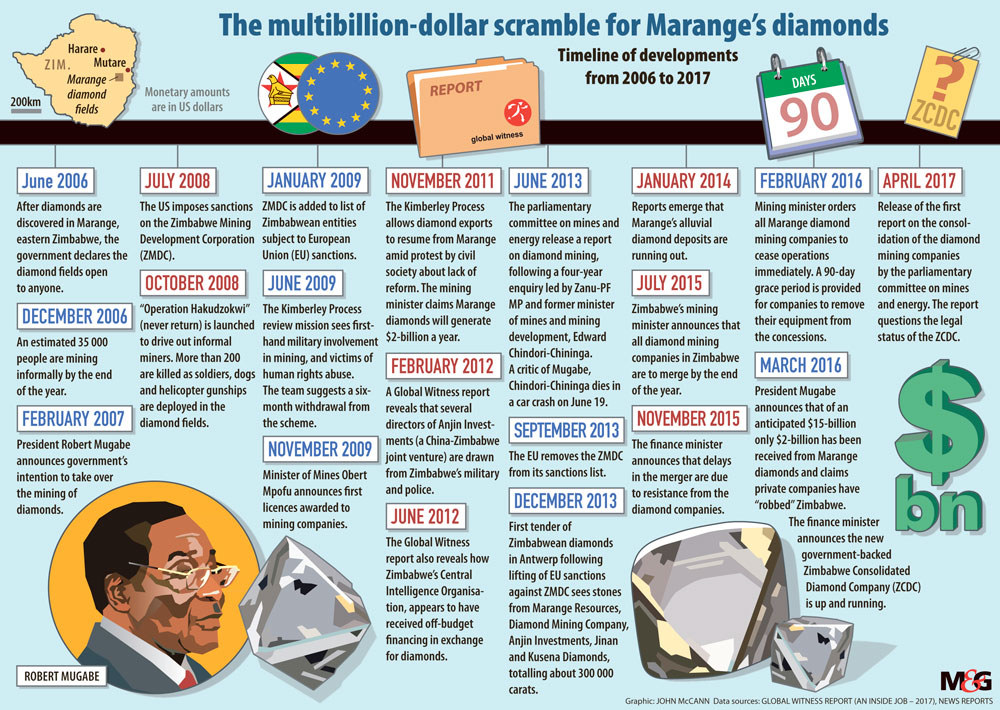

Instead, as a new report from Global Witness confirms, most of Zimbabwe’s vast diamond wealth has been looted by various branches of the ruling regime. Billions of dollars have been lost to private companies with links to the military, the intelligence services, and President Robert Mugabe.

The looting is so blatant that even Mugabe himself remarked on it, in a speech ahead of his 92nd birthday last year. “We have not received much from the diamond industry at all…I don’t think we’ve exceeded US$2-billion or so, and yet we think that well over US$15-billion or more has been earned in that area.”

The president blamed the private companies involved in diamond extraction. “The companies that have been mining have virtually robbed us, I want to say, of our wealth…You cannot trust a private company in that area. None at all.”

What Mugabe neglected to mention was that these private companies are all 50% owned by the state — which makes the state complicit in any illicit activity — and that some of these missing funds are being secretly funnelled into different factions within his regime.

“Global Witness has uncovered new evidence that reveals how Zimbabwe’s feared Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO), the military, notorious smugglers, and well-heeled political elites, all gained control or ownership of companies operating in Zimbabwe’s diamond fields,” said the international investigative outfit.

This is not entirely new information, of course. There has long been suspicion that Zimbabwe’s diamonds are being exploited by for personal or political gain by the country’s major powerbrokers, and previous Global Witness investigations have shed some light on how this works. Former finance minister Tendai Biti last year described all the diamond companies operating in Zimbabwe as a “cabal of rogue elements” that had siphoned off, by his calculations, a staggering $2-billion per year.

But the new report, titled An Inside Job: The state, the security forces and a decade of disappearing diamonds, based on years of painstaking research, is the most comprehensive account yet: it sets out in forensic detail how the billions have been stolen, and where they are ending up.

The report uncovers how Zimbabwe’s intelligence and security forces are intricately involved in all aspects of the diamond trade – and how this props up the ruling party.

“Global Witness’ research into the joint venture companies operating in Marange has revealed a number of links between Zimbabwe’s feared and highly partisan intelligence organisation, the military, and three of these companies: Kusena, Anjin, and Jinan. Through these links, Zimbabwe’s CIO and military have secured themselves a potentially lucrative source of off-budget financing,” says the report.

“This kind of independent financing undermines democratic and civilian oversight of powerful state security services, leaving these institutions free to act independently with fewer checks and balances. This, in turn, incentivises these same institutions to preserve the power structures that afford them access to these funds. In Zimbabwe, where security forces are closely aligned to the ruling party ZANU-PF, this arrangement serves both parties by shoring up a system that maintains the security sector’s loyalty and the ruling party’s power.”

Another company, Mbada, which holds the largest concession in Marange, is revealed to be controlled and part-owned by Robert Mhlanga, a close associate of President Robert Mugabe.

Zimbabwean officials did not respond to Global Witness’ efforts to obtain comment.

Despite the obvious flaws in Zimbabwe’s diamond industry, Zimbabwean diamonds continue to enjoy certification from the Kimberley Process – an international stamp of approval. This raises serious concerns about whether the Kimberley Process, which is supposed to prevent these kinds of abuses, is still fit for purpose.

“The Kimberley Process was set up to stem the flow of conflict diamonds, but the definition remains rigid and narrow,” says Global Witness. “‘Conflict diamonds’ are limited to ‘rough diamonds used by rebel movements or their allies to finance armed conflicts aimed at undermining legitimate governments’. In a country like Zimbabwe, where state institutions profiting from diamonds, not rebels, are implicated in undermining democracy and serious human rights abuses, the Kimberley Process remains silent. Member states have shown no political will to amend this definition.”

As the Marange diamonds become harder to reach, the Zimbabwean government is amalgamating all private companies into one entity known as the Zimbabwe Consolidated Diamond Company. While this move presents an unprecedented opportunity to reform a rotten industry, it is also a chance to make it even more exploitative.

As Global Witness concludes: “Zimbabwe’s diamond industry is at a crossroads. Remaining reserves are dwindling and are more difficult to mine. But they remain lucrative enough to command the attention of both the government and private investors. A decade of disappearing diamond wealth, aided by a culture of impunity and secrecy, has shaped an industry captured by vested economic interest, rivalries, and mistrust. These are now playing out more publicly than ever, as rival interests compete for what can still be salvaged from the wreckage of a find that once offered such promise.

“The Government of Zimbabwe has sought to tighten its grip on the sector by amalgamating all its mining licences into a single new company — the ZCDC. If these efforts are successful, the government may secure greater control, though the signs of genuine reform remain to be seen. Evidence to date suggests the ZCDC will be run with the same opacity that has frustrated oversight and accountability in the past, while retaining many of the actors that have shaped the sector for the past decade.

“Of greatest concern is perhaps the prospect of Zimbabwe’s security sector — including the CIO and sanctioned ZDI or another entity connected to the army — securing a stake in a far greater proportion of Zimbabwe’s diamonds than they have enjoyed to date. If ZCDC does emerge as Zimbabwe’s only diamond mining company, and includes actors linked to the security forces, this may serve only to further entrench the economic interest of the security sector in the diamond industry.”