Identified as an activist and propagandist

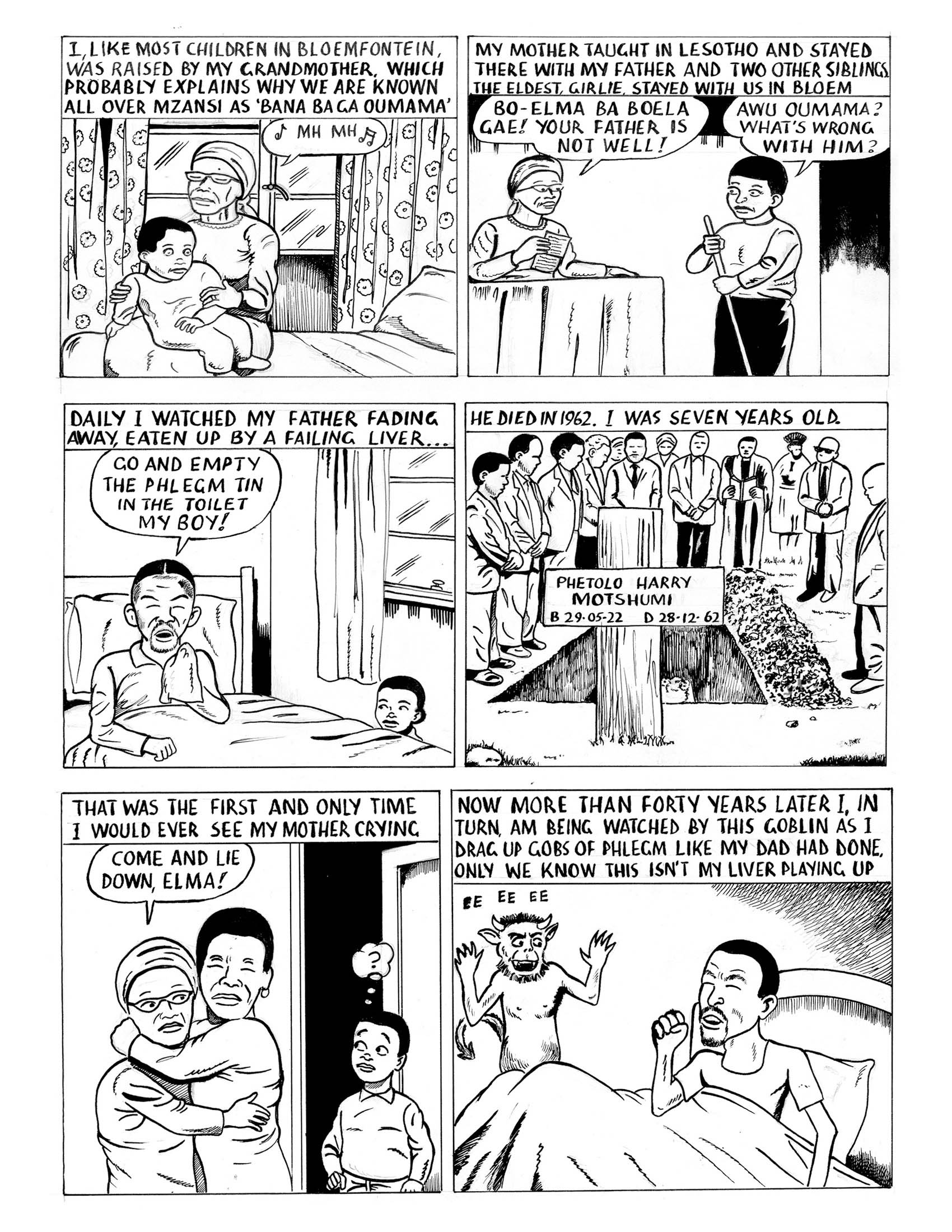

The abiding image of cartoonist Mogorosi Motshumi is that he is softly spoken and somewhat self-effacing. The frames of the artist’s graphic autobiographical trilogy, of which The Initiation, the first of three parts, tell a different story.

[The Initiation is the first long-form graphic autobiography produced by black South African comic artist]

Motshumi, his life in a constant state of flux, discovers comic books as a child, using the sand of the Batho township in Bloemfontein as his first drawing surface.

“I started reading comics at a very young age,” he says. “I would copy the images, but then I saw that I could express myself through this medium. As a child, I was not very talkative, but the paper became a conduit to express my feelings.”

Born in 1955, Motshumi, a multitalented artist (he played the saxophone, wrote and performed poetry), came of age in the turbulent 1970s, imbibing black consciousness almost organically, given the internal situation of the country. His ideological outlook is present throughout the story as a guiding star, first in the honest but sensitive way in which he renders his youth and, later, in the stark political choices our protagonist makes as the security apparatus closes in on him.

Identified as an activist and propagandist, Motshumi is detained for being in possession of banned political pamphlets. After spending nearly two weeks in prison, he is released, only to become paranoid when opening his mail. The death of Onkgopotse Tiro by parcel bomb looms large over him.

The jocular, zany cartooning style that he uses to depict youth gives way to a stoic, noirish template that eventually sees Motshumi head off into a self-imposed “exile” within South Africa’s borders.

But fatherhood is at his door, so our protagonist must pull off the double act of attaining breathing space while not completely severing ties with his newborn son and wife.

“I was supposed to skip the country but I couldn’t do it because my partner was pregnant. By the time she delivered, the police harassment was intensifying. I figured if I went to Johannesburg I could have anonymity, but I didn’t use a pseudonym because I wanted them [the apartheid police] to know that I am still in the country.”

Motshumi drew cartoons for Free State newspapers before settling down into a fruitful, 14-year stint at the adult literacy magazine Learn and Teach. It was a mobilisation and learning resource aimed at the nongovernmental organisation, labour and civic sectors and was started in the days when liberation movements were banned.

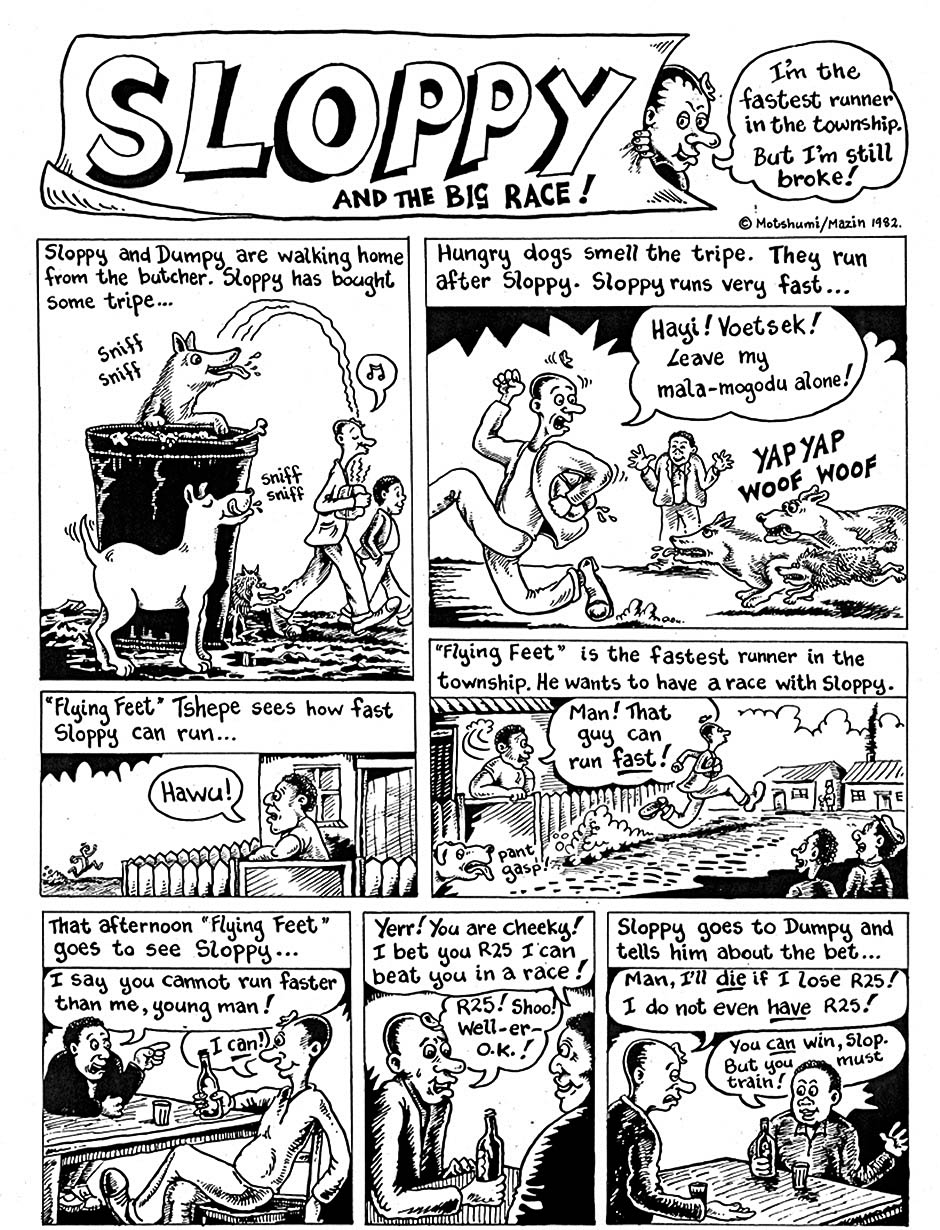

Hassen Logart, a magazine colleague of Motshumi’s, says Sloppy, Motshumi’s popular cartoon strip, made him the only black cartoonist in the 1980s to run a regular strip expressing the everyday life of black people.

[Sloppy was written and illustrated by Mogorosi Motshumi and N.D Mazin, and serialised in Learn and Teach magazine, Johannesburg, 1981-1983]

A taste of Sloppy is appended to the introduction of Motshumi’s elegantly produced autobiographical comic. This particular episode, published in 1987 at the height of the State of Emergency, captures the inferno-like mood that challenged apartheid’s last stand. On a trip home, Sloppy and his friend Dumpy encounter heavy traffic, a roadblock, a petrol-bombed building in flames, a workers’ march and a township eviction before finally reaching Dumpy’s home and pulling out two cold ones.

Without belabouring the point, Motshumi casually outlines self-medication as a coping mechanism. It is a theme he returns to in his artwork. In The Initiation, he confronts his self-destructive behaviour with a clarity born out of distance. Since the book’s release earlier this year, Motshumi’s life story and work is experiencing renewed interest. Two other graphic books will be released by the publishing house Xlibris and an autobiography is also in the works.

“At the moment, I am busy with my memoirs,” he says. “This time it’s not a graphic novel but a written story, with some short stories that complement the memoir. I expect to be done with them in mid-October.”

Asked about the necessity of the memoir, considering the clarity and detail of The Initiation, he says: “Well, telling a story through graphics has its limitations and, over and above that, I didn’t want the pressure of publishers’ deadlines.”

The extraordinary feat here is that Motshumi is doing all this with a debilitating eye condition. “At the moment, I can read and write, but drawing takes a lot more doing. After some minutes of reading, I get headaches. I have been seeing a couple of specialists.”

His eyesight problems stem from an ulcer in his cornea. There is a possibility that the ailment could damage his good eye, but an operation is planned for late next year.

Book two of Motshumi’s autobiographical trilogy focuses on the artist’s Johannesburg years, which lasted from 1980 until 2005, when ill-health forced Motshumi to head back to Batho in Bloemfontein.

In the late 1990s, Motshumi contracted HIV, eventually receiving treatment with the aid of his Learn and Teach colleagues. He remembers his life in Johannesburg as full of “sharp twists and turns … In Jo’burg, I did time for a number of things but most of them were not of a political nature,” he says, hinting at the meagre existence of those days.

Also, there was a lot of outrage, he says. “My bras in Soweto called me an alcoholic. The other day I got a Facebook message from a friend who said he thought I would have long died from this combination of alcohol and rage. It was rather funny to me.”

Following the closure of Learn and Teach in 1994, precipitated by the drying up of anti-apartheid funding, he freelanced before doing a sports cartoon for the Daily Sun. “After my contract ended, they let me go. I was doing sports cartoons, but there was always a little bit of politics mixed in.”

With increased public visibility, even as his own sight deteriorates, perhaps his remaining challenge is how to get his vast archive of cartoons collated into a single book. The thought of it grates Motshumi, who considers the inertia of his former colleagues at Learn and Teach to be less about money than a lack of commitment. “We have met more than once about it, but it doesn’t seem to take off,” he says, betraying a hint of sadness.

His son, Cape Town-based artist Atang Tshikare, says: “His work requires him to communicate with people, but he doesn’t like to do it.”

Tshikare is commenting on the suggestion that his father is shy to the point of hindering his own progress. “He likes to use the work to communicate with people. With him, he couldn’t be talkative because of the political situation [at that time]. Different rules applied then.”

Although Tshikare and his father have worked through their estrangement, collaborating on published and upcoming book projects, one can only hope that the logical progression will be a complete appraisal of this man’s extensive but disparate body of work, it was an oeuvre that provided temporal relief, defiance and humanity in times ruled by hubris and brutality.