Children who enter grade one at the minimum age of 5½ years are at a significantly higher risk of repeating the year than those who wait until they are six to start school, a study has shown

It is a warm Monday morning in Braamfontein’s withering summer. The first school bell has rung and the corridors have emptied.

Nothing but silence remains. Latecomers are a rare occurrence here. Most of the pupils depend on punctuality and a rigid schedule for learning to take place efficiently.

This is not a typical school.

Inside the Sheep Class, a teacher and her assistant are supervising six children. The three-and four-year-olds are silently gathered around a red table for the day’s first lesson. There are white two-litre ice cream containers on the table. Two holes have been carved in each lid – one big and one small.

The teacher takes a ping-pong ball from a big hole and slides it through a smaller hole. She repeats this until all the balls have been transferred.

“Now it’s your turn,” she explains softly to the children.

Some of them follow suit, others don’t. About half an hour later most of the children have managed to move the ping-pong balls.

The first lesson of the day has ended.

A different world

“We do things differently here,” says Ronel van Biljon, the principal of the Johannesburg Autism School.

Autism spectrum disorder is a group of complex disorders of the brain’s development that reduces a person’s ability to communicate and interact with others.

Van Biljon explains: “Autism is not just one condition; it is a spectrum. Some people will have ‘low support’ autism and others a form of autism that requires ‘high support’.

“The latter are unlikely to even learn to communicate and may be dependent on others for the rest of their lives.”

Scientists haven’t managed to identify a single cause for autism because the disorder is so complex. Some studies have found that genetics and the environment could play a role, according to the United States-based medical research organisation Mayo Clinic.

The school has about 300 pupils between the ages of three and 21. “We have a long waiting list. If we could, we would take in as many learners as we can,” says Van Biljon. “But that would compromise the quality of education we offer.”

There are normally between six and 10 pupils, a teacher and a teaching assistant in each classroom.

Autism South Africa’s Vicky Lamb says autistic children require far more attention than pupils in mainstream schools.

“If a teacher has six autistic learners in a class, she’s doing the work equivalent to teaching about 36 children who don’t have autism,” she explains. “That’s why they are accompanied by a teaching assistant to offer the best possible care.”

Beyond the spectrum: Johannesburg Autism School is one of fewer than 10 public schools for autistic children in South Africa. (Hanna Brunlöf)

Beyond the spectrum: Johannesburg Autism School is one of fewer than 10 public schools for autistic children in South Africa. (Hanna Brunlöf)

There are no grades at the Johannesburg Autism School. Instead, pupils are divided into five phases, ranging from a beginner’s to a vocational level.

The Sheep Class is one of 12 beginner’s classes at the school.

Four images are stuck on the wall next to the classroom’s door. The word “arrival” is written in bold at the top. The first photo shows a little boy removing his lunch box from his bag. Next to it, there’s a picture of a pigeonhole filled with lunch packs. Then one of a little boy hanging his bag on a rail and, finally, one of a classroom toilet.

There are many similar sequences on the classroom walls. At the work station, in the bathroom and even where they eat their lunch.

This is how the children learn basic routines.

Lower classes have animal names. As the children grow older, classes are named after colours.

About one in five parents who send their children to the school is unemployed, says van Biljon.

It makes it hard for them to afford the school fee of R1 430 a month. “Close to 60% of the learners don’t pay, mainly because their families can’t afford to,” she explains.

Some of the unemployed parents work as teaching assistants.

Research shows that parents cope better when they are able to reduce behaviour problems, like self harming, in their young autistic children. (Hanna Brunlöf)

It’s lunchtime in the Sheep Class. The teacher points to the photo that instructs the pupils to fetch their lunch boxes from the pigeonholes. With tiny yellow trays, the children carry their meals to a square blue table where they will eat.

The teacher and her assistant also bring out their lunches to encourage the little ones to eat.

Most of the children in the beginner’s class have recently been diagnosed with autism.

“This is the most challenging, yet important, phase of their learning – not just for the children but for their parents too,” says Van Biljon.

The wellbeing of autistic children depends on their parents’ ability to follow a strict schedule and work with their children’s teachers.

A 2013 study published in the Brain & Development journal found that parents who are able to reduce behaviour problems in their autistic children cope better and have less stress as a result.

“This is the single most important thing for autistic people. They need to be reassured that things will happen in a certain order,” says Van Biljon.

As lunchtime continues, a boy pretends to be asleep on his chair. “He doesn’t want to eat his lunch,” his teacher smiles. “He only wants to eat sandwiches with cheese.”

No one knows how many children in SA are living with autism but one thing is for sure, there are less than 10 public schools for them.

Autism can only be diagnosed by specially trained doctors, such as paediatricians, neurologists, psychiatrists and neuro-developmental specialists.

Without a diagnosis, parents cannot apply to get their children into specialised schools.

The earlier the condition is identified the better, says Lamb.

But a 2016 study found that autism is not discovered early enough in young children because of a shortage of health facilities equipped to diagnose the condition in the first three years of a child’s life.

Public schools for autistic children in South Africa are few and far between and information about where they are situated is also scarce.

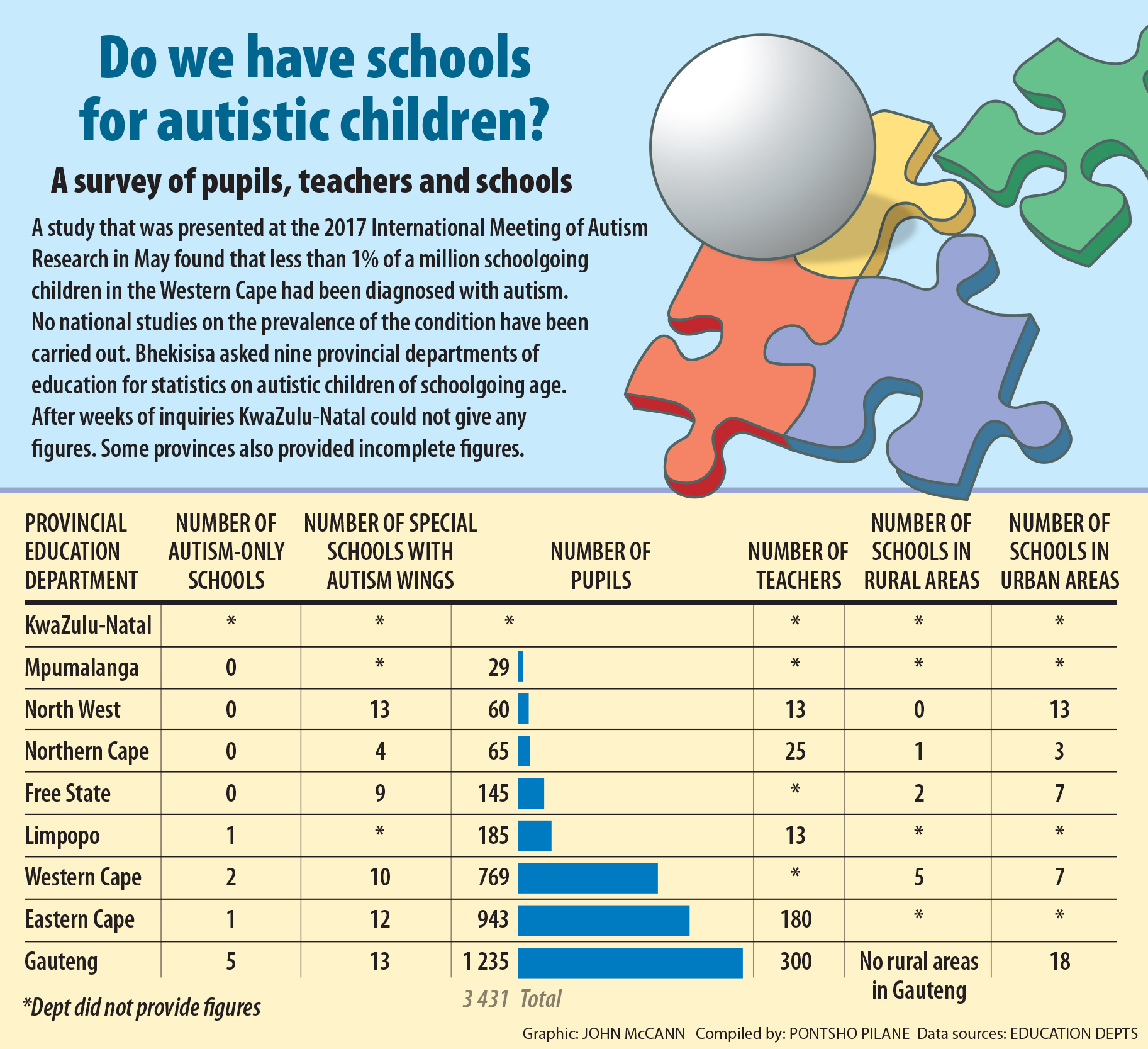

Bhekisisa asked the nine provincial departments of education for statistics on autistic children of school-going age.

The data shows that there are less than 10 autism public schools in South Africa. Only four provinces were able to provide all the information that was requested (see graphic).

There are no figures for how many children, or adults, have autism in sub-Saharan Africa, according to a 2014 study published in the Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities journal.

Researchers found this is because of the lack of “standardised screening and diagnostic tools validated for African populations”.

Tomorrow always comes

The school day ends when the clock strikes two.

Scores of adults – some parents, others designated drivers or guardians – walk to various classrooms to fetch the children.

A teacher stands at the door with a register. Pupils are not allowed to leave without an adult signing the register. “This is for safety reasons. We understand that our learners are vulnerable and we want to ensure that we can protect them as much as we can,” says Van Biljon.

Using the bathroom is the last activity for the Sheep Class.

The children then remove their bags from the rail, collect their now empty lunch packs from the shelf and return them to their bags.

The teacher and teaching assistant wave the children goodbye. Some wave back, others don’t.

Tomorrow, it will all begin again.