'Throughout her life

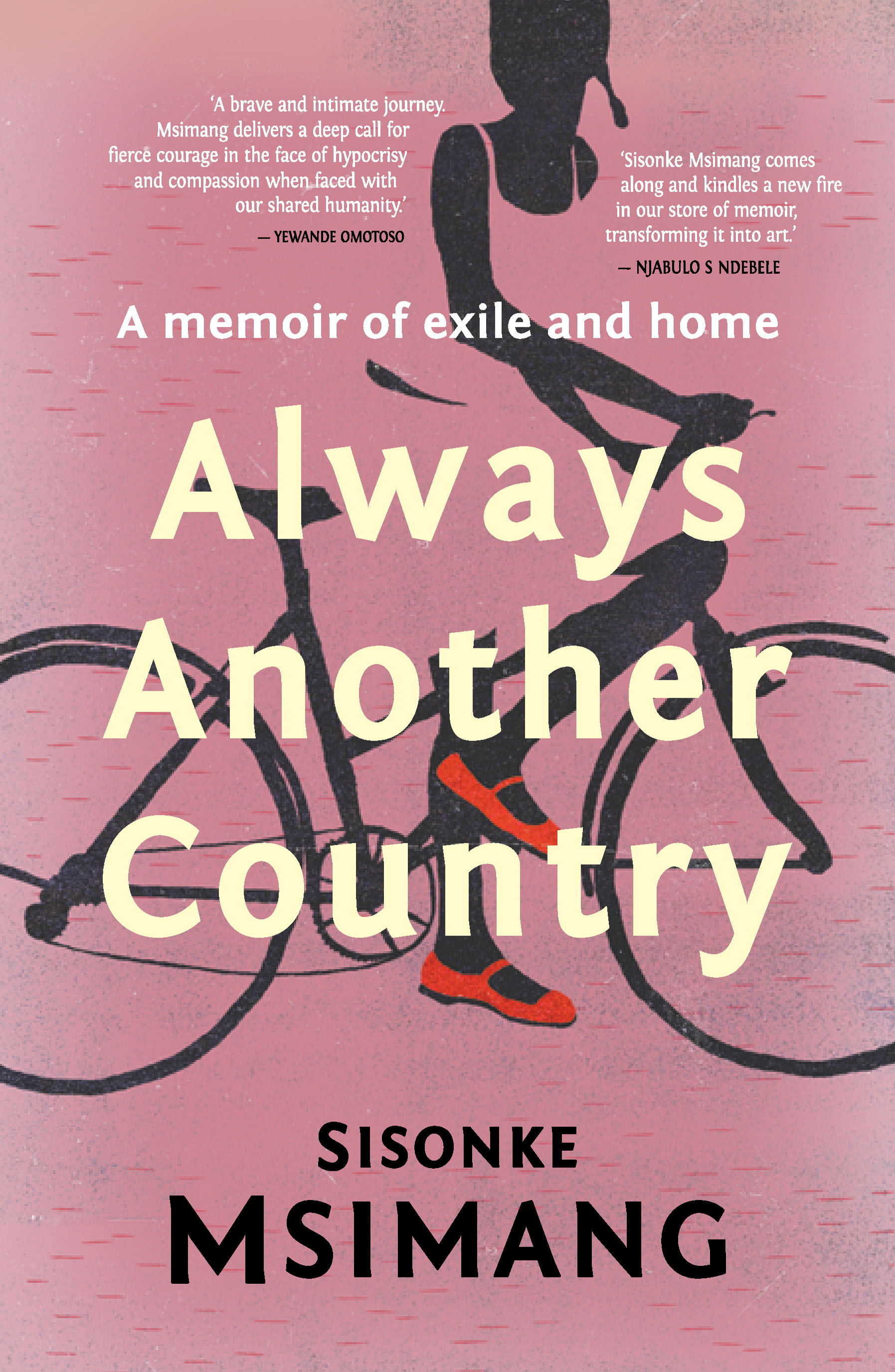

ALWAYS ANOTHER COUNTRY by Sisonke Msimang (Jonathan Ball Publishers)

This has been quite a year for black women’s writing. The floodgates are wide open and fiction, nonfiction and poetry are gushing out with an impressive urgency.

It is interesting to note that life stories are emerging once again as they did in the 1970s and 1980s, when Ellen Kuzwayo, Phyllis Ntantala, Emma Mashinini, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela and many others put pen to paper in a powerful chorus. Sisonke Msimang’s book has joined this chorus of black women who have used memoir and autobiography to tell their stories, in order to defy the erasure of their lives and significance.

I first approached Msimang’s new book with caution, nervous about what I would find inside the pages. I’ve followed her writing since I first encountered her columns in the Daily Maverick and Africa is a Country. I say follow, but really I dipped in and out of her various essays, depending on what I was thinking through about South Africa.

Some of her writing left me thinking deeply about the representation of black women in public discourse, yet other essays left me with questions that stopped me reading mid-essay, purely out of irritation.

Msimang’s latest book, Always Another Country, seems to have had a similar effect on me. While discussing her book with a friend I found myself saying: “Andifuni ukumwela uSisonke.” I read the book with as little black-girl-magic fervour as I could muster, in order to ward off the temptation of being too critical or too caught up in euphoria.

Ultimately, I was drawn to how Msimang uses memoir to construct her memories, while trying to tell a story that is both personal and political.

In her choosing to write a memoir, she deliberately delivers a book that is not an extension of her columns and political essays. This is a story. “A memoir of exile and home,” she writes. In the prologue, Msimang writes, “This book is both personal and political,” because these aspects are often difficult to disentangle. Perhaps a memoir is the nexus where private and public worlds can unfold.

Although I am sceptical about memoirs as a genre — or perhaps I am sceptical about the reliability of memory — I appreciate the genre for the vulnerability it allows.

This book raises questions about the politics of memory in a country that is finally confronting its collective memory. The illusion of rainbowism has begun to disappear. In choosing to remember her past and the history of South Africa, Always Another Country echoes Primo Levi’s words: “I see memory as a gift but also as a duty. We ought to cultivate our memories, we should not let them go to ruin.”

Like any memoirist worth their salt, Msimang begins with a disclaimer: “This book is a memoir … Some events have been compressed and of course the dialogue I quote as verbatim could not possibly have transpired exactly as I have committed it to the page. Still, I have done my best to ensure this book represents the truth as I know it.”

I discover this fine print once I have read the book, somewhat settling my initial concerns because it allows me to think about the book anew — without the cloud of truth hovering above my reflections.

There are many threads that hold the book’s story and Msimang’s truth together: family, love, intimacy, home, belonging, displacement, politics and identity. There’s even a tinge of nostalgia.

In Msimang’s narrative, these themes brush against each other in ways that made me sigh, wince and contemplate the ethics of our memories. We remember the people, places and things we care about because of the way they have shaped and continue to shape who we are.

Although Always Another Country is about the private and intimate worlds of the author’s childhood, friendships and family, it is also a book in which home becomes a metonym for South Africa. Within this framing, exile becomes a journey to finding the home that she heard adults talk about throughout her childhood.

Hers is the imaginary homeland that Salman Rushdie writes about when explaining his relationship with India in Midnight’s Children: “It may be that writers in my position, exiles or emigrants or expatriates, are haunted by some sense of loss, some urge to reclaim, to look back, even at the risk of being mutated into pillars of salt. But if we do look back, we must also do so in the knowledge — which gives rise to profound uncertainties — that our physical alienation from India almost inevitably means that we will not be capable of reclaiming precisely the thing that was lost; that we will, in short, create fictions, not actual cities or villages, but invisible ones, imaginary homelands, Indias of the mind.”

Throughout her life, Msimang is haunted by this sense of an imaginary homeland and carries the burden of what South Africa, home and belonging mean for her. As someone who does not share this burden in quite the same way, I begin to get the sense that she carries this burden disproportionately, and at times, alone. But, of course, anyone who cares about South Africa and what it means to belong carries this burden.

Perhaps hers is also the burden of what it means to be an ANC exile child. Msimang explains that she “was born into an Africa that was waiting for me and into a movement that needed children as emblems of the future. We were totems, all of us — grand experiments who were testaments not just to our parents’ love but to the ability of the struggle to regenerate, to sustain itself … All across the continent we were Africa’s promise, middle-class children who were birthed with the sole purpose of walking away from the past with determination and absolute confidence.”

I wince when I read this. I am overwhelmed by the specialness of these middle-class ANC children who are being groomed for a future that does not yet exist, where they can be anything they want to be.

But can they?

Perhaps. If only to be the “new blacks” I read about in Msimang’s chapter “New blacks, old whites”. It seems the new South Africa has created different roles — caricatures at times — for blacks and whites to play, depending on where one stands on the finite line of privilege held taut by the binaries: the haves and the have-nots.

I am not convinced by the so-called “newness” of the blacks Msimang describes, because I read them as an iteration of the educated elite of the late 1800s or the “New Africans” of the 1930s who were avid readers of The Bantu World. They could also be a version of what Dennis Brutus referred to as the “new un-African” in 1962, a group he viewed with some derision because they lacked the kind of radicalism he expected of Africans at the time.

Msimang would probably challenge Brutus’s derision because the black people she writes about are her family and friends who have perhaps earned the right to be exceptional because freedom allowed them to be who they wanted to be.

In this way, the burden and longing for home morphs into the burden of privilege at various points in the memoir. And the burden becomes a disappointment when the dream of moving into a new home on the affluent Congo Road shatters into a nightmare of violence for Msimang’s young family.

Here, the imaginary homeland becomes a problem that cannot be fixed, because the protection that class privilege sometimes offers cannot shield anyone from the reality of a fraught South Africa. Although she writes about a range of issues with candour and openness, I am too aware of the author’s need to explain her complicity in the imperfect system in which she holds “shares in South Africa Inc”, a task she undertakes with great anxiety.

If you are an avid reader of Msimang’s work, read the book if you want to know about the life of a woman who is on a journey searching for home.

Although Always Another Country is both a story and an analytical project, it also raises many questions about the disappointments of the new South Africa — disappointments of education, social capital and middle-class privileges that no longer act as buffers.

If you appreciate the dance between memory, fiction, history and nostalgia (with a dash of vulnerability for good measure), Always Another Country is highly recommended.