Perhaps the fest was not terribly interested in attendance

When it comes to festivals, I am generally a gluttonous human being, making elaborate maps of just how many sessions I can cram in, only to find that FOMO (fear of missing out) has a double agenda: to push you to see more, and to keep you plonked to your seat until the session you are tuned into is done.

If the programming is tight, and you know exactly what you’re missing when, the FOMO is that much easier to deal with.

My experience of the first day of the Nirox Words Festival was that the programme became irrelevant the moment the clock struck 11.30am and I was still staring at an empty amphitheatre with the expectation of watching Madala Kunene and Lamakhosi Kunene (set down for 10.30am) quickly fading away.

[Madala Kunene. (Henry Engelbrecht)]

When Lamakhosi eventually took to the stage, probably after midday, it was not with Madala Kunene, but a group of musicians who played stripped-down music with bare humanist lyrics about interfamily relations. The performance, which featured a dancer, was ostensibly cut from two chapters in Professor Mazisi Kunene’s uNodumehlezi ka Menzi, the original isiZulu manuscript that yielded the epic poem Emperor Shaka the Great.

The music, incantatory and repetitious, seemed to lack completion. This is less in respect of its form but rather in its delivery, which lacked force and propulsiveness.

For a significant part of this two-day festival, the amphitheatre would play host to the Kunenes, whose primary mission was to draw attention to the recent publication of the initial Zulu manuscript uNodumehlezi ka Menzi. Not to call the intervention counterproductive, but I have had the honour of listening to a clip of Mazisi Kunene in full flight. His ability to make the words spring to life from the page, not fleetingly, but in a manner that renders them perpetually alive in one’s own being, is one of the pillars of Kunene’s practice.

The amphitheatre slots, which included a performance by Jessica Mbangeni and a reading by Kunene’s son Zosukuma, functioned more as teasers rather than as new engagements of the work.

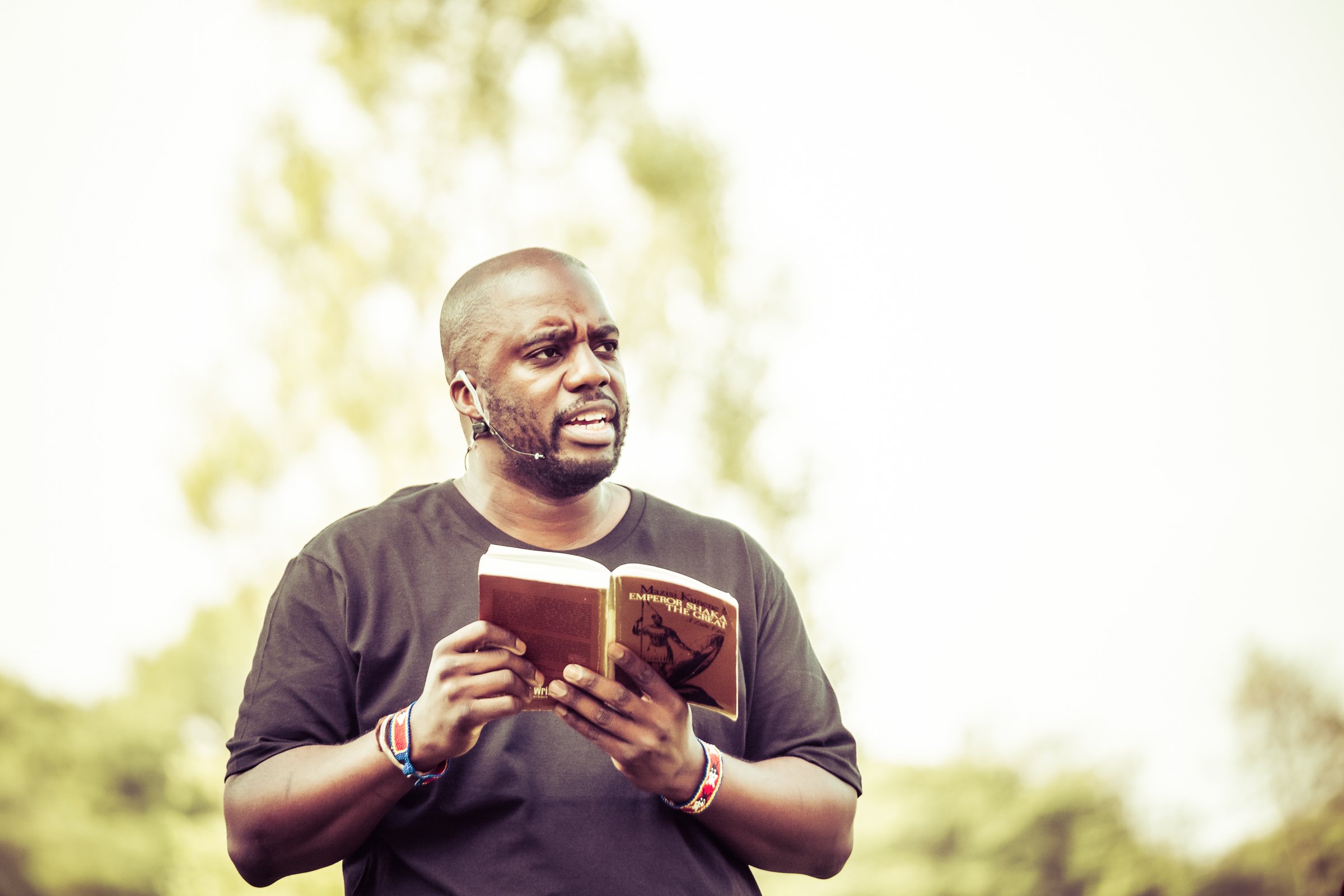

[Zosukuma Kunene. (Henry Engelbrecht)]

Overall, the programming of the amphitheatre was reflective of much of the festival, in the sense of its ambition and reach but lack of a clear curatorial focus. With some of the already-mentioned factors combining to create confusion among the crowds, it soon became a festival of word of mouth, happy accidents and, in some cases, cancelled or lacklustre panels because walk-in traffic was not enough to sustain lively engagement.

Saturday, doubtlessly, belonged to Taiye Selasi in conversation with Bongani Madondo. Teasing out strands from her novel Ghana Must Go, it was a panel that generated wide interest, and proposed new ways of looking at the meanings of afropolitanism and its attendant parallels of middle-classness and nationalism. There was many a reference to Selasi’s TED talk, which questions the idea of countries as monolithic and “eternal”, but there was also clear evidence of the text’s deep resonance — in a myriad of ways — with various readers.

Host Bongani Madondo did well to open up the discussion to audiences who brought their own reading of the text to bear on Selasi, who reciprocated with warmth and rigorous engagement. Drawn out and eventually clocking out at 90 minutes, it was nevertheless one of the more memorable panels I have attended in recent memory, thanks to the tight focus of the discussion.

With this being the first Nirox Words Festival, it is perhaps an important hint to future editions of the festival.

Sunday, for me, kicked off to the sounds of Urban Village (a polyglot band somewhere in the range of psychedelic mbaqanga) playing from the Miriam Makeba songbook.

There remained questions in my head about the point of such easy revisionism, a theme of a day that saw Chris Chameleon resonantly channelling Ingrid Jonker and the Scottish duo of Michael Pedersen and Scott Hutchison adroitly channel the angst of a nation that willingly chose to stay colonised.

Not to frown on Urban Village’s interpretations of Makeba (they bring their particular brand of showmanship to any ticket), yet they sounded much better at the helm of their own material, as they were an hour later at the West Lawn, when their set with Lebo Mashile failed to materialise.

Perhaps the best way to put it, as one punter suggested to me, was that it was as if the Nirox Words Festival was perhaps not terribly interested in attendance. There was hardly any discernible pre-event marketing, a lack of enthusiastic hashtagging and the staging, coinciding with the week when the slaving masses are on their knees, suggested a bent towards exclusiveness.

With tighter curation, and perhaps more thought into how wide ranging sensibilities can be harnessed into a tighter whole, the Nirox Words Fest should be an interesting environment in which to enjoy a literary life. But as it stands, at R360 for a day pass, R180 for a bottle of dry white and at least R80 for some sustenance, it is not for the short pocketed.