(Graphic: John McCann)

COMMENT

Equal Education members from the rural Eastern Cape are pushing forward with the nation’s growing call to hold state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to account. Recently, Equalisers — high school members of Equal Education — picketed outside the offices of the Coega Development Corporation in East London and Port Elizabeth.

Coega is a state-owned enterprise and one of eight agents in the province that provide managerial support. It is responsible for implementing the project to build schools in the province for the national and Eastern Cape departments of education.

Like Eskom, the Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa and SAA, Coega has been allocated public money to do work on behalf of the government and, in the 2017-2018 financial year, it was allocated R262-million to build school infrastructure in the Eastern Cape.

Coega’s chief executive, Pepi Silinga, will earn R4.6-million this year but the rural schools his organisation has committed to build or fix are still in crisis.

In the Eastern Cape, which has the biggest infrastructure backlog in the country, there are 800 schools built of mud, wood, corrugated iron or fibrecrete.

According to the latest national education infrastructure management system data, in the Eastern Cape, there are 1 955 schools with pit latrines or no toilets at all, 53 schools with no water supply and 177 schools with no electricity. This is all in violation of the law.

The legally binding Minimum Norms and Standards for School Infrastructure state that, by November 29 2016, all public ordinary schools had to have access to water, electricity, proper sanitation and not be made of inappropriate materials.

The poor performance of implementing agents such as Coega is not an Eastern Cape problem alone but it has compromised the ability of the Eastern Cape’s Accelerated Schools Infrastructure Delivery Initiative (Asidi) to fix the schools with the worst infrastructure backlogs.

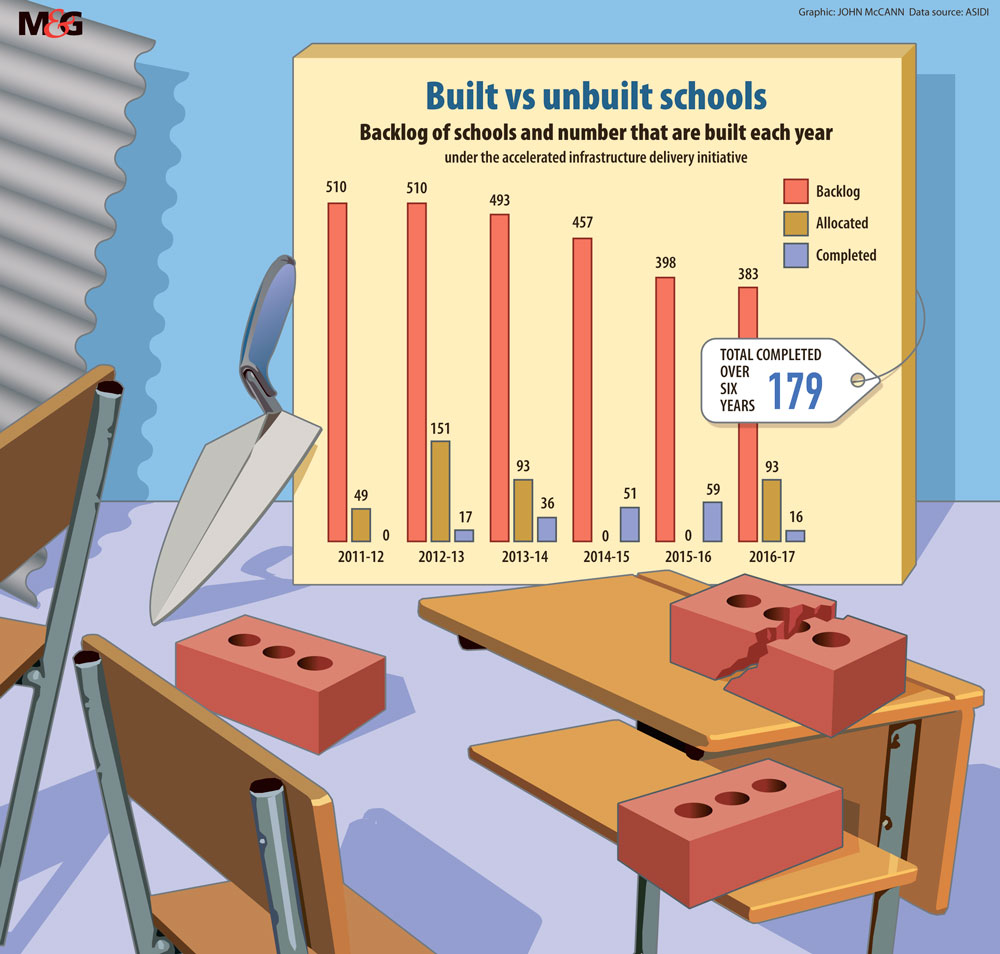

The aim was to build 510 schools in three years but only 179 schools have been built in six years.

This number is extremely low, and worrying, considering the backlog and the number of schools allocated to an implementing agent.

Coega, which has been an implementing agent for Asidi since 2012, is involved in more than 900 ongoing school infrastructure projects, many of which are are suffering from poor or incomplete service delivery, the result of poor contract management and internal controls.

Coega is responsible for procuring and managing contractors and professional service providers to build school infrastructure, and takes a management fee of between 6.5% and 10% of the total cost of the project.

A team of Coega employees evaluate contractors’ bids behind closed doors and school communities have no say in deciding on a contractor. Eastern Cape department of education officials are invited to attend procurement committee meetings but rarely do, and the minutes of these meetings are never released.

Procurement committees’ decisions can be contested in court, for example, by a contractor that believes that it should have been awarded the tender.

But court proceedings inevitably lead to Coega cancelling a contract and restarting the tender process, delaying the provision of school infrastructure even longer.

The latest auditor general’s Public Financial Management Act report revealed that Coega’s procurement processes were uncompetitive or unfair. The auditor general also found that Coega’s board did not exercise adequate oversight to prevent noncompliance with relevant legislation.

According to the report, Coega has been slow to deal with areas of risk, instability or vacancies in key positions, and key officials lacked competence.

Coega was responsible for R3-million of the provincial department of education’s irregular expenditure last year, which is under investigation. It was also responsible for the fruitless and wasteful expenditure of another R8-million — which could have provided 95 toilets or 11 classrooms.

The department is also investigating allegations that Coega stopped and terminated projects even though it had already incurred expenditure.

On average, Coega project managers handle between 40 and 45 projects each, whereas the ideal would be 10 projects each. Overstretched project management results in poor contractor oversight, few site visits and little to no communication with communities on the progress of school projects.

Two schools on Coega’s project list are the Vukile Tshwete Senior Secondary School, which is housed in precarious wooden structures, and the Hector Peterson High School, which is waiting for Coega to build a new building, a toilet block, an administrative block and a nutrition centre.

Equalisers from these two schools took matters into their own hands and demanded that Coega must provide a written response to service delivery failures and provide temporary infrastructure solutions for schools in which infrastructure poses a threat to pupils, where there are insufficient toilets, and where the sanitation facilities are unhygienic, within 30 working days.

The protesters have demanded that Coega must add contractors that have failed to fulfil their obligations to the treasury’s database of restricted suppliers to bar them from future government contracts. Coega must also penalise contractors and professional service providers that don’t meet deadlines.

When the group of Equalisers and Equal Education staff arrived at Coega’s offices in East London, they were met by security guards who tried to intimidate them.

But the Equalisers were not swayed — nor would they be. Weeks before the picket, Equal Education requested a meeting with Coega to discuss some of the projects assigned to it. But it said a meeting would have to be approved by its client, the Eastern Cape department of education.

Equalisers believe that SOEs such as Coega are obliged to account to their real clients — all South Africans, including pupils, parents, teachers and communities.

When Thembeka Poswa, Coega’s programme director for the department of education portfolio, finally accepted the protesters’ memorandum in East London, her 32-second speech failed to address the core challenges faced daily by poor working-class pupils and teachers.

Equal Education is aware that solving the education infrastructure crisis will not be as simple as reminding SOEs that they are being watched, or that they are also accountable to the public — and not just to the state.

The nongovernmental organisation believes a wake-up call to Coega is a first step for pupils who have been failed — an important first step towards the creation of a state that works to undo the unequal rural-urban education system created by years of underfunding.

The education crisis in the Eastern Cape and the questioning of the role of SOEs in our society strike not only at the heart of today’s political milieu but also at the country’s goals to redress historical inequalities, Equal Education claims.

Luzuko Sidimba is the head of Equal Education Eastern Cape and Nika Soon-Shiong is an Equal Education researcher