'A practical first step to address Zimbabwe’s economic woes is to deal with the liquidity crisis

The change in Zimbabwe’s leadership this week could spark confidence in the economy but substantial political and policy reforms are needed to sustain it, analysts say.

“A new hope has been created … there is a sense of relief, there is freedom of expression, freedom of association,” Harare-based economist Vince Musewe, said after President Robert Mugabe’s resignation on Tuesday.

From the jam-packed streets of Harare to Johannesburg’s Hillbrow, euphoria followed the announcement that Mugabe’s 37-year chokehold on the country was over.

Musewe said Zimbabwe has been in a state of paralysis, with a dysfunctional government focused on internal political battles rather than the economy. “Any move away from that is welcome,” he said.

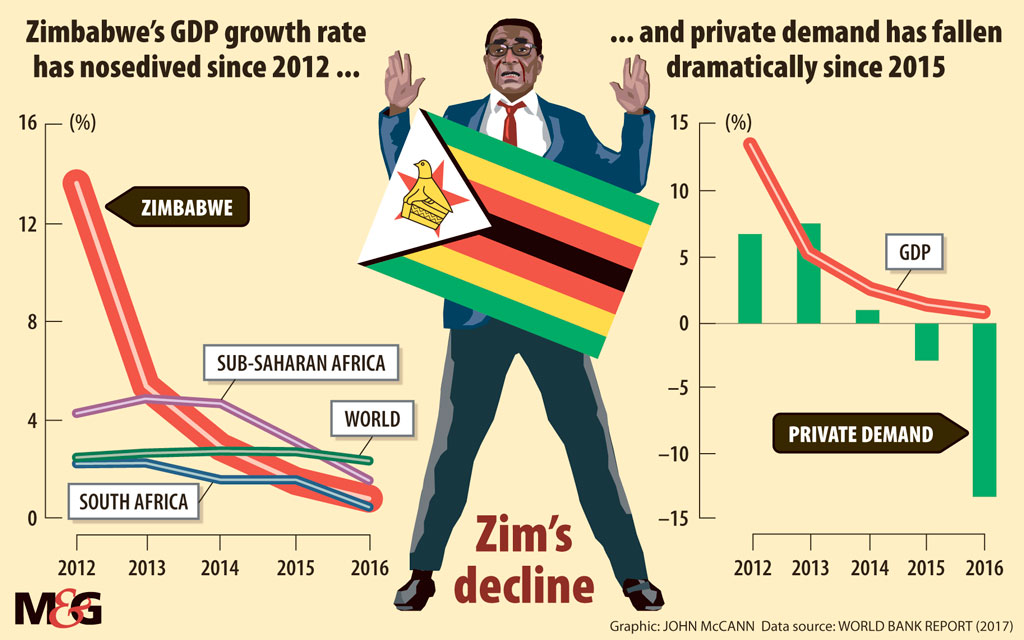

The country’s economy has been battered under Mugabe’s leadership, most recently suffering a severe liquidity crisis. The shortages of hard currency led to the introduction of bond notes, a pseudo-currency pegged to the US dollar. The crisis was driven by declining foreign direct investment, a ballooning trade deficit and soaring government spending, despite diminishing revenues.

The country’s budget deficit was 9% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2016, according to the World Bank, and public sector debt rose to $11.4-billion, or about 70% of GDP.

But the deficit is likely to get worse and reach more than 11% of GDP, or $1.82-billion, for 2017, according to recent reports from the Zimbabwean finance ministry.

Meanwhile, the public sector wage bill, which accounts for 90% of government revenue, has curtailed spending on services such as social welfare, education and infrastructure.

The introduction of the bond notes prompted fears of a return to the hyperinflation of 2007 and 2008, when inflation reached about 80-billion percent, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) figures.

But Emmerson Mnangagwa (dubbed “The Crocodile”), who will be sworn in as president on Friday, comes with a lot of political baggage, Musewe said. A Zanu-PF stalwart and long-standing supporter of Mugabe — until he was axed in an abortive move to make way Mugabe’s wife Grace — Mnangagwa was party to Mugabe’s misrule.

It is essential for him to address this, said Musewe, and to adopt a more investor- and market-friendly rhetoric. His first test will be to pick a competent team using an inclusive approach, Musewe said. This includes appointing a credible finance minister and possibly apolitical professionals and technocrats.

A practical first step to address Zimbabwe’s economic woes is to deal with the liquidity crisis.

A core part of the country’s trouble is trade and investment and its limited exports, which make it difficult to earn hard currency, resulting in the liquidity problems, said Peter Draper, the managing director of Tutwa Consulting.

But the key questions are how to kickstart exports and how to attract foreign investors, he said, adding that joining the Southern African Customs Union could be an option, as it would curb the Zimbabwean government’s discretion to manipulate trade policy, open up access to the South African market and give Zimbabwe duty-free access to the smaller member countries.

The customs union would also allow Zimbabwe to join the common monetary area, bringing it formally into the rand monetary zone with access to rand liquidity, Draper said.

The common monetary area is a sub-arrangement of the customs union, noted Draper, and although it has been joined by Namibia, Swaziland and Lesotho, in effect it places monetary policy under the influence of the South African Reserve Bank.

But Neville Mandimika, Rand Merchant Bank’s Africa analyst, said this would come with “huge caveats” regarding monetary policy and fiscal co-ordination.

Mandimika said a more likely option would be for Zimbabwe to approach development finance institutions like the IMF and World Bank.

“This would immediately create a policy anchor and give international investors some comfort over the financial management of the country, making it easier to have a conversation about bringing money in, either through portfolio flows or foreign direct investment,” he said.

In the long term, however, Zimbabwe’s leadership will have to tackle more politically contentious economic policies, such as the Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Act, which requires foreign companies operating in the country to cede 51% of their business to indigenous Zimbabweans.

The law, which has been inconsistently applied, has to be reformed to create policy predictability and encourage foreign direct investment to return, Mandimika said.

Musewe said government expenditure and soaring debt have to be tackled, as must blatant corruption and smuggling to address “leakages in the system”.

More broadly, the judiciary’s independence and police brutality must be addressed to “change the narrative of who Zimbabwe is”, he added.

“In the long term, we can turn Zimbabwe into a $100-billion economy. We have the skills, we have the resources. We have only been lacking the political will and the leadership,” Musewe said.

But Draper warned that all of this is contingent on how the politics play out.

Elections are due to take place late next year but Mnangagwa and Zanu-PF could seek to capitalise on the wave of popular support they have gained by removing Mugabe and push for early elections, he said. But Musewe said various reforms would need to take place before a fair election could be held, including reforming the security sector and Zimbabwe’s electoral commission.