Athi Patra Ruga's oeuvre fucks with the exclusion that is the norm of black womanhood and queer femmedom

Athi-Patra Ruga’s avatars are black women — subversive, confrontational, playful, complex, brave. His oeuvre fucks with the exclusion that is the norm of black womanhood and queer femmedom, and challenges audiences to imagine a future where these people, who are often not considered people, are left to be.

Beiruth walks through the flat industrial yellow light and concrete of the taxi rank. Or, rather, she stalks it, haunting the hollow luminescence in white fishnet stockings that mark delineations on her legs.

The camera focuses, holding tight at her flank: a hand swinging at its side and next to it, the partial view of a red onesie stretched over her ass; above it, a sign in white and blue reads “Atlantis”.

Something covers her head and her face. It flickers, muted in intervals. The onesie is also rigged to flicker with the colours of the spectrum. A man in a white wife-beater leans, cocks his head to one side, and holds out his arm for attention. Another stops in his tracks, stares animatedly.

A woman in black shimmies for Beiruth, or the camera. From somewhere, a non-diegetic voice asks: “You tryna fuck me?”

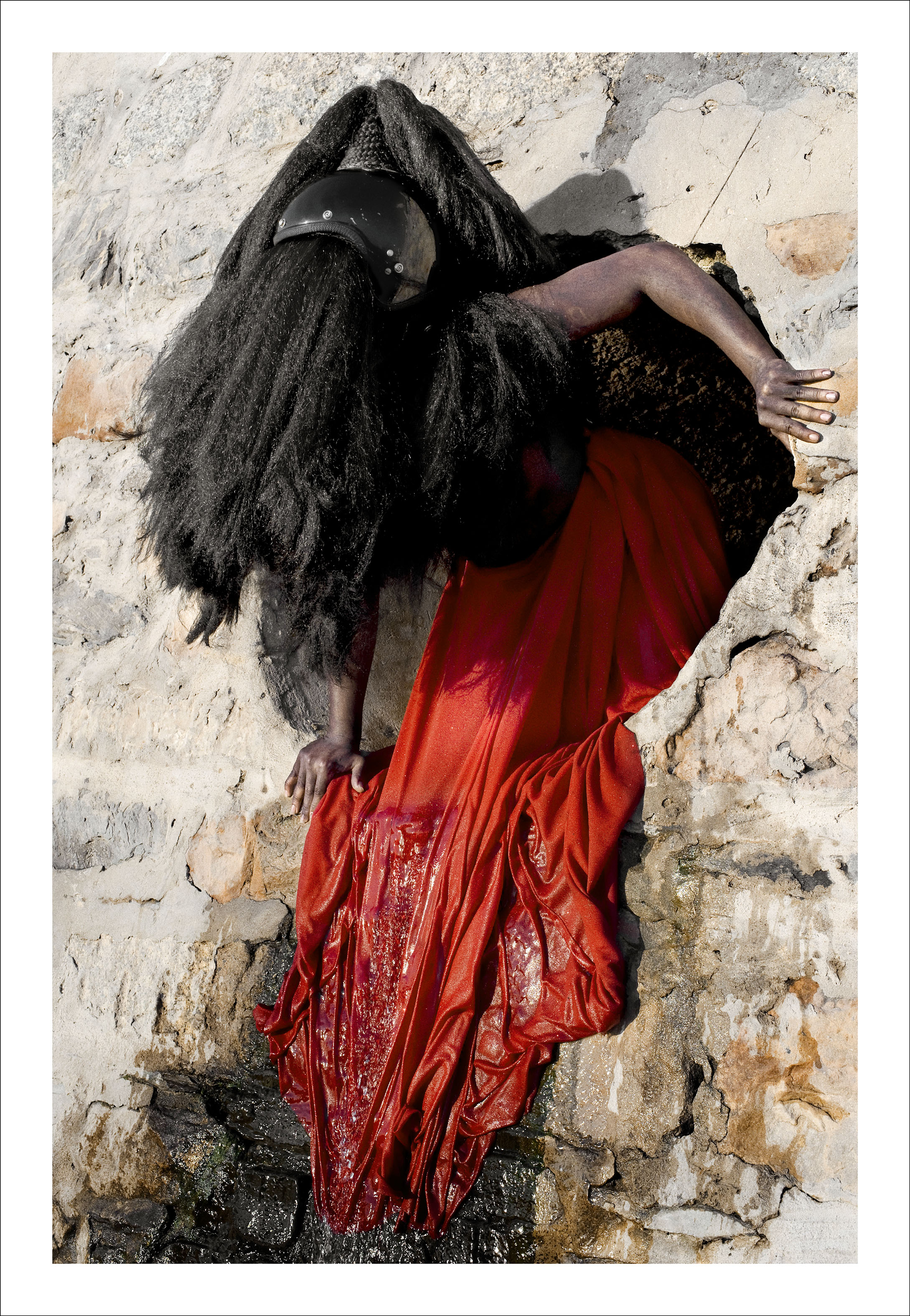

With the onesie belted around her waist she stands, splayed against the wall of the Universal Church, her back and palms flat under the blue crucifix.

She moves slowly, horizontally, as if navigating the face of a cliff.

Her hand feels the wall, tentatively at first, then reaching for the white grating that secures the church entrance. She puts one high-heeled leg out, finds a footing, and spins her body, pirouetting into position.

And then she climbs, her helmet obscuring and obfuscating. She stays ready for the eventuality of a man trying to crack her skull one day. She has a hole on the top of her head, or she is avoiding one.

Are you trying to fuck me?

[The embodiment of Beiruth (The Death of Beiruth), served as the first in a series of subversive iterations of matrilineal lineages]

***

Johannesburg, 2008. Ruga weaves loose threads into fabric.

The president of the Republic has been recalled by the governing party and, from Ruga’s apartment downtown, he has a window view of the xenophobic violence that we later term the “miniskirt attacks”.

Beiruth was born here. She is the bastard child of Jo’burg Clubland’s fluorescent strobe lights and the violence of that time. Beiruth was born against ideas of women and femininity, and against the notions of nationhood.

***

In White Girls, American writer and theatre critic Hilton Als writes: “We were Barbara Smith and her twin sister, Beverly, and their feminism and socialism, and we understood every word of what Barbara meant when she and her co-editors titled their 1982 anthology All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, But Some of Us Are Brave: Black Women’s Studies.”

Ruga is not a black woman, but his avatars are. Or rather they present as femme and, accordingly, draw the attention that a black woman’s body does.

They wear heels and helmets. They walk past glares and jeers. They seemingly exclaim: “Are you trying to fuck [with] me?”

“My work is very femmecentric. I want to bring femme queer dreams into the world, into art. There is a legacy of the imagination, imagination as affirmation,” insists Ruga.

***

We see this legacy of imagination with Miss Congo in her bleached denim number — a red bandana furled around her crown. She lies on her back, on a raised concrete platform. In her hand, a block of cloth which she embroiders, screaming at intervals. She lies again, another hard wall, another heap of dirt and broken things, red and white miniature airplanes. Diaphragm rising and lowering encased in gold.

These are altars of her making, blood lust and body as sacrifice. Who wants a tired sacrifice? Why do we fatten our beasts before the slaughter? We feed them whole and keep them hydrated. Here, Ruga’s altar lies in wait, too tired to be a sacrifice, baptised in things too hard that can perhaps be allowed.

***

In another of Ruga’s creations, Future White Women of Azania, the women are loud to the point of garishness. Here, the arms and legs of delicate, petalled things appear in hues of pink and amber, crimson, white and blue. Their torsos expand — amorphous spectrums of helium extending upwards and buoyant.

These are the things the rainbow nation absorbed. Spat out. They are pretty, but not beautiful. And in the colours they parade, nothing about them says they are white.

He laughs when asked, as if it should be obvious, if it’s a joke we are all in on. He responds with the kind of flippancy that familiarity can breed.

“I mean, come on, white can mean many things. It can be white as in mhlophe, msulwa. Pure of the past and the future,” he says. “And it could also be white women. White like the kids who are being told ukuthi benza izinto zabelungu. When they want a particular kind of safety or beauty or even luxury. Right? Aren’t we told that those are white woman things?”

***

In the seminal documentary Paris is Burning, the reference in the title is a Paris of the imagination. In the same way Ruga’s Azania is the product of hope and myth.

A few minutes into the documentary, Pepper LaBeija — the American drag queen and legendary mother of the House of LaBeija — flips through a magazine, looking at one “beautiful white woman” after another.

Commenting on their two-dimensional selves, positioned as the epoch of humanity, vulnerability and freedom, she asks: “Why is it that they could have that and I didn’t? I always felt cheated. I always felt cheated.”

In another scene, trans icon Octavia St Laurent points to a poster pasted on the wall, her red-tipped fingers running their way down the page. “This is my idol Paulina. Someday I hope to be up there with her. If that could be me, I think I would be the happiest person in the world.”

***

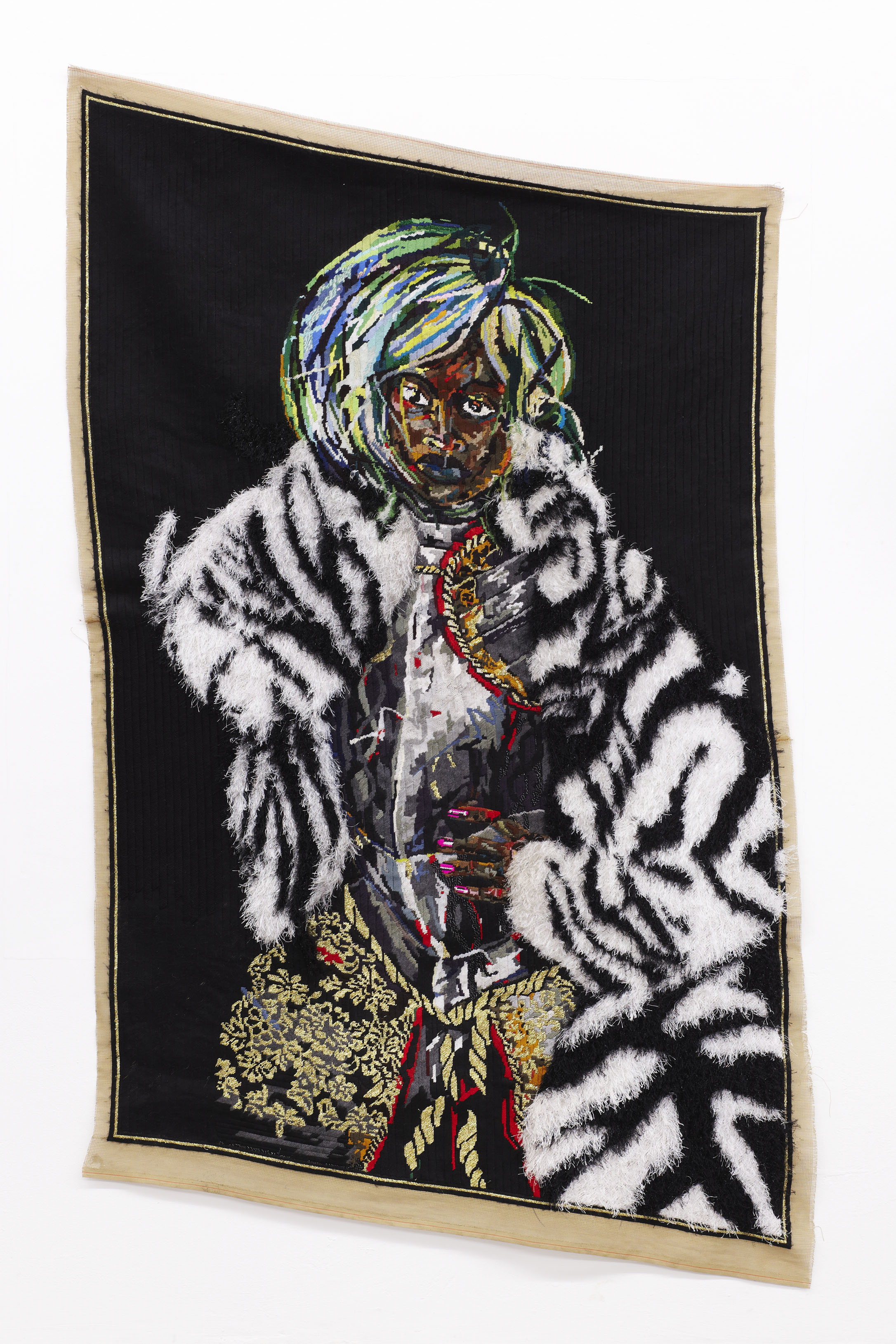

Ruga’s versatile Queen Ivy appears in darkness, shot from the back. A little light moves in small ways, evoking words like shimmer, glitter and glint.

[“Are you trying to fuck me” (Athi Patra Ruga)]

The queen walks and the viewer’s eye shifts between her and other things of shine and pearl, of dark and iridescence. A voice gives instructions, the intended recipients of which are unclear.

“Khululeka.” “Sebenzisa amehlo engqondo.” “Ncuma.” “Ubhale iblessings zakho.” “Manginibuza ukuba ubani inkululeko emagameni akho.” “Ewe. Yes. Please. Thank you.”

“Now keep the picture in mind, to refer to from time to time,” the voice commands in English, as Queen Ivy holds what appears to be a dompas in her gold-gloved hands.

The pass is placed on a vanity table.

Queen Ivy is seated at a dressing table, its mirror bordered in lights. This is another altar for the Alters, and it contains in its lights all the blinding things, things garish and gold.

We hear a robotic recitation of Brenda Fassie’s Weekend Special.

A small porcelain pickaninny figure on the table. A crystal vase, a gold jewellery case perched atop a hardcover copy of Valley of the Dolls. She looks into the mirror, but in the juxtaposition of the objects on display, she is the bleeding away of a myth.

The dompas on the table belongs to Ruga’s grandmother, but the other items belong to the versatile queen. In this construction of her universe — this future Azania — the performer and the performance couple in a way that obfuscates and storifies. A construction on top of a construction.

In the performance, Queen Ivy gets up from a stool, walks to the centre of a stage and begins to dance, something of a desperate celebration — a ritual whose purpose we are not yet privy to.

She is soon joined by other avatars, other inhabitants of this cosmos who parade themselves in colour.

Here, the piece picks up the “Makubenjalo” refrain dropped from the national anthem. Images are superimposed on to the queen’s face: Feral Benga, Steve Biko, Simon Nkoli, Felicia Mabuza-Suttle, Winnie Mandela, Brenda Fassie.

The other avatars surround the bandaged walking wound undressing her, tending to her. Or is it Ruga they tend to, now stripped of the queen’s gold and glitter? In the end, she is left naked on display. A Versatile Queen Ivy Venus Hottentot. A wound undressed without redress.

***

Fred Moten writes, in In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition: “Between looking and being looked at, spectacle and spectatorship, enjoyment and being enjoyed, lies and moves the economy of what [Saidiya] Hartman calls hypervisibility. She allows and demands an investigation of this hypervisibility in its relation to a certain musical obscurity and opens us to the problematics of everyday ritual, the stagedness of the violently (and sometimes amelioratively) quotidian, the essential drama of black life, as Zora Neale Hurston might say.

“Hartman shows how narrative always echoes and redoubles the dramatic inter-enactment of ‘contentment and abjection,’ and she explores the massive discourse of the cut, of rememberment and redress, that we always hear in narratives where blackness marks simultaneously both the performance of the object and the performance of humanity.

“She allows us to ask: What have objectification and humanisation, both of which we can think [of] in relation to a certain notion of subjection, to do with the essential historicity, the quintessential modernity, of black performance?”