Go: The people of Sasolburg’s Zamdela township are fed up with the ANC.

The ANC’s woes in Metsimaholo in the Free State started in 2014, when 320 workers belonging to the South African Municipal Workers’ Union (Samwu) went on strike and were subsequently fired by the municipality.

They had downed tools over grievances varying from pay progression, corruption and medical aid and pension disputes to other gripes that crop up regularly in industrial action.

They had been persuaded by their union and the South African Communist Party (SACP) to defer their fight with the municipality until after the 2014 general elections, and went on strike on June 17 that year.

“We met with the comrades in Samwu as the SACP,” says Pakie Letsie, regional secretary of the communist party in the area. “We also engaged the ANC, at the level of the REC [regional executive council]. Everyone acknowledged that they had very real grievances.

“But we also agreed that to go on strike and have a fight with the municipality before the elections would cause chaos. It would hurt the ANC.”

[Collapse: Joblessness and poor services and infrastructure fuel people’s discontent in the Free State town (Delwyn Verasamy)]

But once the elections were over, the fighting resumed, and the ANC found itself, not for the first time, at odds with its alliance partners, organised workers and working-class communities, which have been the backbone of its support since at least the 1980s.

Despite attempts at mediation — involving the SACP and the ANC’s regional deputy chairperson Brutus Mahlaku, who was then serving as the mayor of Metsimaholo — the employer and unions could not find common ground and the strike began.

There is still disagreement about whether the strike was protected, but a Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA) dispute resolution process upheld the legality of the employer’s move.

Regardless of who was right or wrong, the rift has never healed. There were no formal resolutions or statements but the ANC lost the support of Samwu in the area, and with it that of the trade union federation Cosatu, to which Samwu is affiliated. It would later lose the support of the SACP as well, when the party decided to use Metsimaholo as a test case for contesting elections on its own.

Most ominously for the ruling party, the fault line drew in the working class and poor communities of Zamdela and other townships around Sasolburg. The dismissal of 320 workers in the small industrial town had ripple effects throughout the community. Unemployment is high in Sasolburg and its surrounding areas, and so too is poverty.

The municipality’s uncompromising action was seen as a direct attack on the poor, and a demonstration that the ANC no longer cared about them.

Letsie says: “We warned them the ANC would face a tough time in the local government election. But they didn’t listen.”

They should have listened. The SACP was still playing by the tripartite alliance script but the support from the unions was lacklustre at best.

Large swaths of the working-class townships stayed away. The ANC bled. Although the ruling party won 16 of the 21 Metsimaholo wards, and was comfortably the largest party in council with 19 of the 42 seats, it was hurt badly by the stayaway seen in urban working-class constituencies around the country.

The ANC won most of its wards convincingly, with many of its candidates winning about 60% of the vote. But, in all the wards it won, turnout was severely depressed. Overall turnout was only 57%. The ANC won 16 wards, but only three proportional representation (PR) seats, whereas the Democratic Alliance won the remaining five wards, but more than doubled its representation with seven PR seats. The Economic Freedom Fighters took no wards, but dominated the PR race, with eight seats.

In the coalition negotiations that followed, the ANC was consigned to the opposition benches as the DA led a group of the smaller parties, with the EFF pledging its council votes to help the minority government function.

The people of Metsimaholo had jettisoned the ANC simply by staying away.

Similar scenarios were played out in urban and peri-urban townships in August last year, leading to the ruling party losing the Tshwane, Johannesburg and Nelson Mandela Bay metros.

If the trend holds, the ANC — like Zanu-PF in Zimbabwe — will increasingly become a party of the rural vote and some urban elites, at best ignored and at worst reviled by the middle and working classes in the cities.

Metsimaholo could very well tell us whether the trend will hold.

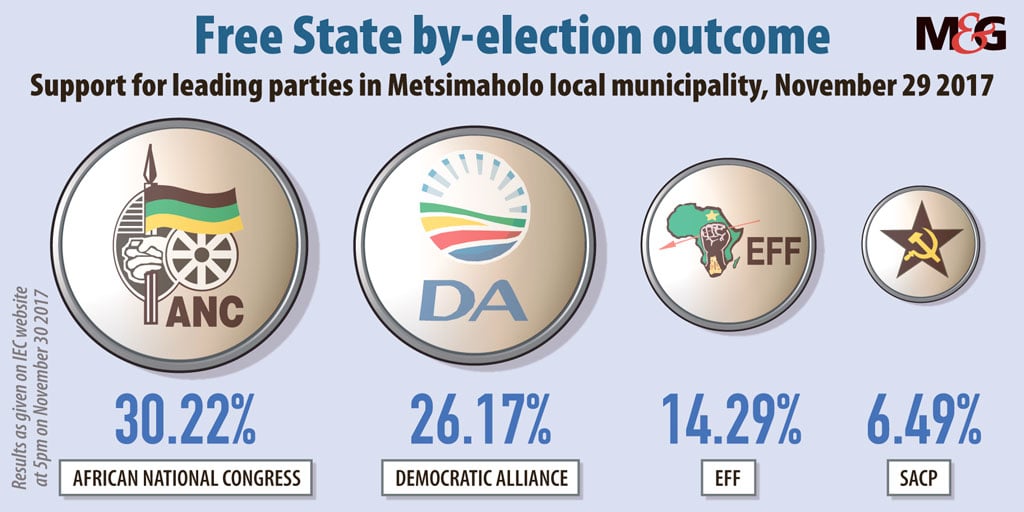

This week the people of Metsimaholo did it all over again after the unstable coalition government collapsed in July. The by-election attracted more attention than normal, as national media, commentators and other parties wondered whether the voters in a small Free State industrial town would be the first to move from passive rejection of the ANC (staying away from the polls) to more active opposition (campaigning and voting against the ruling party).

The presence of the SACP as a participant is an intriguing signpost. The party moves in the same circles as the ANC does. It knows the same communities and voters. Has it sensed a vulnerability in its old alliance partner that can no longer be ignored, one it now thinks is better exploited by itself rather than the DA and EFF?

The SACP in Metsimaholo tells the story that it is the residents of the municipality who have finally persuaded the communist party to break with tripartite tradition and challenge for its share of power.

“Workers are putting more pressure on the SACP over the behaviour of the ANC in power,” says Mashel Semonyo, the party’s candidate in Zamdela’s ward eight.

But this is a double-edged sword. Many in the township, and no doubt in townships around the country, see the communist party as too closely linked with the ANC and its failures to effect real change.

In addition, working-class communities might feel the SACP could still abandon them if they get their own way in the palace politics playing out in the ruling party, with no commitment to independence in the long term.

Armstrong Likobo, an EFF branch secretary in Zamdela, says: “The SACP has been in alliance with the ANC for a long time. We [the community] don’t trust them.”

It is a sentiment the 105-year-old party has confronted for the first time on the stump this week. If the communist party is truly committed to the course and no matter the outcome of this by-election, it will face this sentiment again in 2019 and 2021, and in other by-elections in between.

Amy Musgrave and Vukani Mde are founding partners at LEFTHOOK, a Johannesburg-based research and strategy consultancy